Articles/Essays – Volume 48, No. 4

The Brick Church Hymnal: Extracts from an Autobiography

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

New York, 1988–90: DIY

In 1988 I completed my bachelor’s degree in music composition at BYU and moved to New York where I began a graduate program in ethnomusicology. I became disillusioned with the state of classical composition as I knew it at the time and felt that, although I wanted to continue to pursue my lifelong dream of being a composer, I would realize that dream more fully by enriching my musical study with music I had not yet encountered from other cultures. New York had the advantage of an underground jazz scene about which I knew as much as one could learn in those days from hanging out in the imports sections of record stores and reading esoteric music ’zines.

I arrived in New York and took up residence in a tiny windowless apartment owned by the university that was literally in Times Square. This was the pre-Disneyfication, red light version of said Square. After a year of 1,000-page-a-week (by such authors as Malinowski and Levi-Strauss) seminars, I realized that there was little room in this rigorous and demanding discipline for a person with my artistic aspirations. I was also unsuccessful in getting gigs, or in hooking up with similar-minded musicians. So, after getting married, I dropped out and worked for the next year as a bike messenger and a temp word processor while my wife completed her undergraduate degree. In one long-term temp job, I found I had a lot of time with little to do but look busy at my computer. This was long before the internet or computers with graphical interfaces, so I had to come up with something to keep my fingers and eyes busy. I began doing things like designing staff paper, writing poetry, and typing, formatting, and printing the writings of others. I realized that in an office with computers, printers, photocopiers, and binding machines, I had everything needed to produce, even to publish, collections of writing and/or musical notation. All the infrastructure associated with publishing for centuries seemed to melt away. One heard about “desktop publishing” quite a bit in those days. It all seems so quaint now, but it appeared to me that we were on the cusp of a new DIY era. In recorded music, cassettes had eclipsed records owing to their relative cheapness, and portability (both of the media and their playing devices). It was easy to produce homemade cassettes and with a dual cassette deck, one could cheaply “mass” produce a cassette “release” on a small scale.

Nevertheless, the first cassette release of my own avant-garde jazz music garnered little interest and did not allow me to penetrate the downtown music scene. My wife, Lara Candland, was writing fascinating minimalist poems and stories, many of which were accepted for publication by Gordon Lish of The Quarterly. This pioneering journal shut down before it was able to put out the bulk of what Lish had accepted of her work. She continued to submit her work elsewhere, but had less success being taken seriously by other, more aesthetically timid journals.

I had also been going through my father’s (C. Thomas Asplund) unpublished and published poetry, typing it, and archiving it in computer files. He published poetry in Dialogue and Sunstone, but had pieces rejected by them. I was fascinated and a little perturbed by the very detailed rejection letters that betrayed a lack of openness to work that challenged hardened aesthetic and genre definitions and assumptions. Lara’s rejection letters, though much shorter, contained similar messages: “We liked your work, but weren’t sure how it fits in,” or other words that seemed to say, “We’re not sure this is poetry,” etc. I had certainly experienced the same with my own music in trying to share it with others. It seemed that getting published or getting gigs required creating the “right” stuff, stuff that fulfilled certain orthodoxies. Moreover, it seemed that the only non-official Mormon periodicals were scholarly and somewhat dissident in nature, while I had little interest in intellectual resistance but a great deal of interest in artistic expression that was radical in form and texture. I began to realize that I was part of a scattered group of marginalized Mormon artists—marginalized within the Mormon learned and artistic groupings because of geography and because of the orthodoxy of the oppressed, and within the larger secular community because of our identification with a weird religious minority. I also realized that most of the artists that I admired through history were similarly out of the mainstream. In fact, the history western music is mostly that of composers who had great influence over generations that followed, but who were out of the mainstream of their own time. Moreover, many of these artists practiced what we now call DIY. Two of my favorite poets, Blake and Whitman, are good examples.

During this time of searching and discovery, our Manhattan ward had a kind of crafts expo, where members set up booths or tables to show off things they did or made. I decided to “desktop publish” a prospectus of a new Mormon arts periodical called The Brick Church and drum up subscriptions at the expo. We got about twenty subscribers and ended up producing and distributing two issues of the journal, the first being a ’zine containing poetry and fiction, the second a cassette of eclectic independent music. The first issue was prefaced by something of a manifesto for Mormon DIY art that cited the home production movement during Brigham Young’s administration and recent technological advances that, among other things, suggested a path for a more vibrant Mormon artistic flowering that did not seek legitimacy or precedent from the mainstream.

In my New York sojourn, I also encountered Michael Hicks’s excellent Mormonism and Music,1 which introduced me to Boyd K. Packer’s talk at a 1976 BYU fireside that spoke directly to LDS composers. The talk was, and continues to be, controversial among LDS musicians and artists in that it chides them for various reasons, including the age-old sin of bringing too much artifice into the liturgy. I particularly remember Hicks citing Mormon composer Merrill Bradshaw, saying that the talk “chopped the philosophical feet out from under me,” because Bradshaw saw his role as a composer to bring together the musical discoveries of all ages in the same way that the dispensation of the fullness of times was bringing together spiritual truths from all of human history. I found Packer’s talk as troubling as anyone, but I was also strangely inspired by certain statements such as “the greatest hymns and anthems of the Restoration are yet to be composed.” Also, “If I had my way there would be many new hymns with lyrics near scriptural in their power, bonded to music that would inspire people to worship.” And, after saying that inasmuch as the most impactful works of Mormon art, such as the sublime panels of C. C. A. Christensen and “I Am a Child of God” were created by artistic outsiders, he expected that precedent to continue. However, “the ideal, of course, is for one with a gift to train and develop it to the highest possibility, including a sense of spiritual propriety. No artist in the Church who desires unselfishly to extend our heritage need sacrifice his career or an avocation, nor need he neglect his gift as only a hobby. He can meet the world and ‘best’ it, and not be the loser. In the end, what appears to be such sacrifice will have been but a test.”2

This felt like a worthy challenge for a Mormon composer. I had experienced “composition” as it existed in my world to that point as the writing of esoteric, intricate scores to be played often poorly by oft-grudging technicians if they were played at all. A composer seemed to be judged by the extent to which his or her music embedded some kind of inscrutable cohesiveness within gratuitously incoherent or unappealing musical textures. This may seem unkind or disloyal to a discipline and a group of people that I love. I have since come to a much better appreciation of the scene and its aesthetic ethics. Nonetheless, the atonal hegemony within the American academy was still pretty strong at that time.

Packer’s implicit challenge interested me in its directness and boldness. Could one simultaneously utilize and transcend conservatory training to produce pieces of music that had both the transformative musical power of the modernist music I was trained in and loved and the brevity, simplicity, and appeal of the great hymns of the restoration?

San Francisco/Oakland, 1990–93: Composer’s Books

In 1990 we moved to the Bay Area where we began masters’ degrees at Mills College, long a bastion of experimental music. Seminars were quite different. The emphasis was on giving students space to develop their own (sometimes very unusual) artistic voice. Often classes required virtually no outside work. During one such a class, the great Alvin Curran told us about a project he worked on during a period when he was not receiving commissions. He decided he would keep a book of compositions, that he would add a new composition each week. The pieces would be mostly flexible in their potential realization and rather simple, certainly not requiring virtuoso performers. The pieces were written principally to fulfill a work regimen and to fill a book, rather than for specific performances. Performances would occur later for which he could easily adapt pieces from the book. I also encountered Cardew’s The Great Learning and other similar self-collected anthologies by Zorn, Billings, Braxton, Ashley, and Wolff.

Each of these composers created a book or books of compositions without specific performances in mind. The audacity and faith of these acts of creation were very inspiring to me. They provided a model for me to approach the challenges given by Packer and Kimball.3 I began composing hymns as an artistic and spiritual practice, rather than for specific academic assignments or performance opportunities. This gave me the freedom to write whatever I wanted or felt inspired to write. While in California, I continued to temp whenever I had free days, to make whatever money I could. After my coursework was done, I spent an entire year working as a secretary, squeezing in composing and rehearsing at odd hours when I wasn’t working or commuting.

Seattle, 1993–1999: The Brick Church Hymnal

We then moved to Seattle where I began doctoral study at the University of Washington. After initially registering with a temp agency in Seattle, I began to feel that any more secretarial work would adversely affect my longer-term goals. I felt inspired to make a vow that inasmuch as I wrote a hymn each week, I would be delivered from the necessity of secretarial work. Lara and I were blessed for eight years with stipends and (non-secretarial) employment sufficient to sustain us until I obtained a full-time, permanent teaching job, after which I felt inspired to discontinue my vow and to write hymns only as inspiration came.

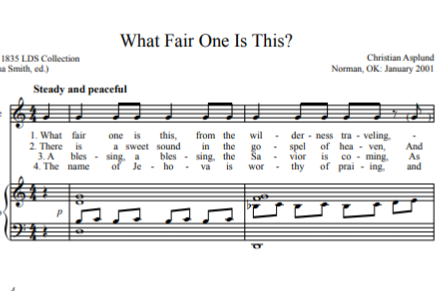

This has been my practice now for fifteen years. I have organized and self-published hymns I’ve written since 1990 in four volumes. Among my composer colleagues I was one of the last to adopt notation software. This is illustrated in these volumes. Volume 1 was released in 1994, volume 2 in 1998, both of which contain only handwritten notation. Volume 3 was completed in 2005 and reflects my gradual adoption of notation software as it contains a mix of handwritten and engraved hymns. Volume 4, completed in 2014, contains only engraved scores. I invoked our earlier publication, The Brick Church, in naming my first and subsequent Brick Church Hymnals. I’m currently two hymns into volume 5. Each volume is quite different and the nature of the hymns has changed with time. During the first two volumes, I was very interested in resetting hymn texts from forsaken and forgotten LDS sources, including the Emma Smith Hymnal. As I ran out of these, I began setting more scriptural texts and writing textless hymns. Volumes 3 and 4 contain considerably more songs for accompanied solo voice than 1 and 2, which contain mainly four-part choral textures. The collections contain some oddities such as songs that I heard in dreams, but that bear little resemblance to any music that I would compose, and items that are more like spiritual exercises than pieces of music. This issue of Dialogue includes samples of my settings of texts from the first Mormon hymnal compiled by Emma Smith. PDFs of all four volumes are freely available at:

https://cfaccloud.byu.edu/index.php/s/5c709b2bb7fe 3bbd6869ac5520e3ab62

https://cfaccloud.byu.edu/index.php/s/78275b4e02a0b 781d7ec44084cc3eacb

https://cfaccloud.byu.edu/index.php/s/4b3a55690585 d62691132b766b6eaeb0

https://cfaccloud.byu.edu/index.php/s/0fe524aedd20361f 7c6453539a96e632

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue