Articles/Essays – Volume 46, No. 1

Home Again: Part Three of Immortal for Quite Some Time

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

I know the standard plot lines, the ones that move from desire to fulfillment, or from desire to fulfillment to tragedy. As this story follows its meanders I don’t find myself to be a satisfied, fulfilled member of my church, but neither is mine the story of a brave individual triumphantly separating himself from an abusive religion. I live chapters of each of these stories. But always intermediary chapters, it seems, never the climactic ones. Absent is the single seductive strand that engages and satisfies—and falsifies. What will it mean to finish this manuscript? To finish writing about my brother? To finish thinking about him? To abandon him again? To jettison this means of access to our past and present experience?

11 November 2012

I went into the LDS Third Ward in Farmington, New Mexico. I could not tuck “my long hair up under a cap” as did poet and environmental activist Gary Snyder when he ventured into Farmington’s Maverick Bar. I had no earring to leave in the car. I didn’t drink “double shots of bourbon backed with beer” (although my traveling bag held a flask of lowland single-malt in case of emergency). Unlike Snyder, I had an escort, an old friend who explained where I was from. Instead of “We don’t smoke Marijuana in Muskokie,” the organist played “For the Beauty of the Earth.” There was no dancing. Otherwise my experience was exactly like Snyder’s.

Snyder was in the Four Corners area to protest the rape of Black Mesa, holy to Hopis and Navajos, black with coal. The corporations prevailed and the coal was strip-mined and slurried away with precious desert water and the air of these high, wild, open spaces was so thoroughly fouled that on Thursday, driving from Cortez to Shiprock, the dramatic volcanic core that lent the town its name stood veiled, smudged, moodily distant.

I was in the Four Corners area to revisit my past, John’s past.

Nearly four decades since I last attended church in my hometown, more than a decade since I left the Mormon Church, twenty years since I began my fraternal meditations after John’s death, a week after Barack Obama was elected to a second term, I went into the LDS Third Ward in Farmington, New Mexico.

A billboard in southwestern Colorado had shouted at me as I drove past: SAVE GOD AND AMERICA. It proclaimed that OBAMA HATES BOTH. And it concluded that I should VOTE ROMNEY.

Utah County, where I live, had just given Mitt Romney 90% of its votes. San Juan County, New Mexico, where Farmington is located, awarded 63% of its votes to Romney (contrasting with Albuquerque’s Bernalillo and Santa Fe Counties, which went 56% and 73% for Obama respectively). With the exception of a few years in New Jersey’s Mercer County (Obama 68%), I’ve spent my life among conservatives.

Farmington’s citizens are conservatives of an isolated sort. It is 182 miles to Albuquerque. 208 to Santa Fe. 419 to Phoenix. 377 to Denver (the route my family took that fateful December). 425 to Salt Lake City (from where Brigham Young sent his son Brigham Young Jr. to colonize Kirtland, New Mexico, a little farming town just west of Farmington). West Texas, origin of many of the town’s oil-field specialists and workers, is about 500 miles distant. At the confluence of the La Plata, the Animas, and the San Juan rivers, Farmington’s Anglo culture is shoehorned between Latino New Mexico and the Navajo Reservation.

I haven’t been politically conservative since I left Farmington. Or did the shift occur when I came home from my German mission? Or perhaps as I changed my major at BYU from pre-med to German literature and philosophy? Or when I headed east for graduate work at Princeton?

In any case, I went into the LDS Third Ward in Farmington, New Mexico, with my long, grey hair pulled back into a ponytail just days after every voting member of this congregation (was there, perhaps, a single dissenter? two of them?) had voted for their fellow Mormon conservative, and had done so after fasting and praying for him, sure, or at least hopeful, that he would save the Constitution and the country from socialism or worse. I live with a partner to whom I’m not married. There’s that problematic flask of whiskey. I had coffee Saturday at Andrea Kristina’s Bookstore and Kafé in downtown Farmington. I swear like the roughneck I once was. I’m allergic to authority. I would gladly be gay if I had those inclinations.

Today I wish I could tuck my hair under a cap.

I pull open the door and gesture to a grey-haired couple to enter.

Thank you, they both say.

When I did this in the old days, people said, thank you, young man, I reply.

You’re not young any longer, the man says.

My friend Doug introduces me to them as the son of my father.

Your dad was our bishop, the man says. A fine man.

I remember John and Dad moving belligerently through the kitchen. There were shouts and shoves. John reappeared with a bag and left the house. As it got dark Dad sat in the kitchen with Mom. I overheard scraps of that conversation and still remember Dad’s heated assertions that he should step down as bishop of our ward, citing Paul’s counsel to Titus: “. . . ordain elders in every city, as I had appointed thee: If any be blameless, the husband of one wife, having faithful children not accused of riot or unruly. For a bishop must be blameless, as the steward of God.” Mom assured him that he was a fine bishop.

Conditioned by Paul’s biases and by the prejudices of a 1950s and ’60s “Christian nation,” our parents helped pass along, or allowed to be passed along, part and parcel with their conservative stability, a subtle racism. I had to confront this again a few weeks ago, waiting at a streetlight. Around the corner came a car with a black male driver and a white female passenger sitting intimately close to him.

My stomach turned.

A bowl of nuts for the holiday season: hazelnuts, peanuts, walnuts, pistachios, pecans, and nigger toes. That’s what we called them at home.

Standing next to the east goalpost of the football field at Hermosa Jr. High, a fellow seventh-grader gleefully and perhaps maliciously informed me there were creatures in the world called “homaphrodites.” Incredulous, yet believing, I instinctively acted to brace up my crumbling world, erecting the first, but not last, phobic pillars to protect me from those hitherto unknown, still faceless, but now named “homos.”

Dad taught science and math at the junior-high school before he became principal. As a science teacher he had access to mercury and to our delight he brought home plastic vials of it. We split it into quivering masses with our fingers and raced heavy blobs down inclines. Dimes, when rubbed with mercury, glistened like new silver.

Doug and I are greeted by the current bishop’s two councillors, men in dark suits and white shirts and ties and with firm handshakes and sincere smiles that make me think they will not throw me out if they discover I’m an environmentalist. Two young, male missionaries shake my hand, assess me avidly. My hair suggests I might be ripe for conversion. I almost stop to lay out my part in the history of this place, to tell them I helped build this building, home that summer from college, a laborer for the construction company hired by the Church. But in deference to the gathering crowd behind us, and with uncharacteristic good sense, I move on and enter the chapel.

We find seats in the back row next to our old friend Craig. He’s the only man in the building not wearing a tie. I get too hot, he says.

Doug’s wife Tyra plays opening chords on the organ and I join the congregation, maybe 150 white people, in singing a hymn about the earth’s beauty. Although I no longer believe there’s a God to thank for that, I am thankful for the earth and smile when I realize I still remember many of the words. It feels good to sing again, to “join the congregation.” And they are not all white, as I supposed—a young Native American, 12 or 13, sits with the deacons in front of the sacrament table.

A vigorous young woman rises to give the invocation (women were not allowed to pray in sacrament meeting when I was young). Heads bow all around me and I find my own head slightly bowed as well. I watch the woman as she invokes “Our Dear Heavenly Father,” her eyes screwed shut, focused intently on what she is saying. She thanks the Lord for the veterans “who we honor on this Veterans’ Day.” She slips into a well-worn groove to ask that God “bless the leaders of our Church and the . . . and the leaders . . . and the leaders of our nation.”

Although the election is still very much with her, in the end, bless her heart, she fights through the disappointment (and anger?) and completes the blessing.

While a master sergeant in splendid uniform speaks extemporaneously and emotionally about how his duty in Vietnam strip ped him of religious beliefs, faith he regained slowly when he found and joined the Mormons, I remember the mimeographed pamphlet students received during my first year at Brigham Young University: “A Guide to Opportunities Open to the Young Men Faced with the Obligation (Opportunity) to Serve in One of the Armed Services: Prepared by Detachment 855 Air Force ROTC BYU for Bishops’ and Stake Presidents’ Day.”

We gathered, several thousand strong, in the de Jong Concert Hall, where an elder of the Church, Hartman Rector, Jr., spoke to us about duty, obedience, and patriotism, reminding us that “the members of the Church have always felt under obligation to come to the defense of their country when a call to arms was made.” He described the war that liberated Japan as a war used by God to introduce the gospel of Jesus Christ to the Japanese. Ditto the Korean War. And “exactly the same thing will happen in Vietnam. When we pull out the U.S. troops . . . we will move the mission president and the missionaries right in behind them. We will build up the kingdom of God there. Yes, it took some of the best of this nation to do it, but these nations must be redeemed by blood. It’s in the economy of God. . . . Yes, this is God’s nation, and the stars and stripes is God’s flag.”Several years later, in mid-December, when it looked like my lottery number for the draft might in fact be called, I dutifully took a bus to Salt Lake City for a pre-induction physical. I passed, and, well schooled by church and state, I would have gone if the draft for the year had not ended a number or two before mine.

What was John’s experience with the draft? We never talked about the war.

The master sergeant continues his testimony and I picture the flat plaque on my father’s grave halfway out the Aztec Highway. Paid for by the Veterans Administration, placed in a noisy corner below a busy highway in a sterile cemetery designed without gravestones to make grass cutting easier, it says BOB WALTER ABBOTT/1ST LT US ARMY/WORLD WAR II/1925–1977. That’s it. No mention of loving father and husband. Of fine teacher and good principal and compassionate bishop. His epi taph is elsewhere, I tell myself, in our “Books of Remembrance,” in our collections of photographs, in these pages.

John’s gravestone stands in a more inviting spot, atop a hill in American Fork, Utah. Fraternal hands are carved into bright grey granite—and into these meditations.

A woman sitting in front of us rubs her teenaged son’s back, a gesture repeated in other pews. A husband stretches an arm around his wife’s back. Families snuggle together while a speaker drones comfortably on about a new, inspired curriculum for youth classes (“There will be no more ‘stand and deliver’ but interaction and shared responsibility”). I try to imagine John in this warm setting, a 61-year-old arm around his husband’s shoulder, happy to have rejoined the congregation that sent him on his mission to Italy.

I can’t picture it. Not in my lifetime.

We sing “Count Your Blessings,” one of Dad’s favorites, and I cheerfully join in the bass line that marches straightforward eighth notes (“count your many blessings”) across the syncopated soprano line (“count —— your blessings”). It’s a song of trial and triumph: tempest tossed, all is lost, load of care, cross to bear, count your many blessings and angels will attend, help and comfort give you to your journey’s end. Although no one but Tyra at the organ is watching her, the chorister signals for a slowing cadence at the end of each verse, adding the slightest of personal touches to the song.

Sacrament meeting over, I follow Doug across the gym into a large classroom. People still greet him as “Bishop,” formal in their hierarchy, grateful for his service. The room fills with men and women, maybe 60 of us, almost everyone holding a set of scriptures. Christ’s visit to the Americas after his resurrection as told in the Book of Mormon will be the text for today’s class. Doug is a born teacher, as erudite as he is sensitive to the problem of too much erudition in this diverse and provincial group.

Provincial. That’s the word that best describes my sense for the town I drove into on Thursday. I was without sophistication when I left for college in 1967 and thus, logically, must have come from an unsophisticated town. Farmington is nearly twice the size it was then, approaching 50,000 inhabitants, and it now has a two-year college. Still, over the years, thinking about Doug as a hometown lawyer, I have always thought that he was stuck in a backwater.

Cosmopolitan. That’s the word that best describes the new sense I have for Doug after the mental explosion provoked by poking around in his downtown law office. It’s an insight I might well have expected had my thoughts not coalesced around an inevitably false and self-serving image. In high school we frequented the school library in tandem and as college roommates I was jealous of Doug’s passion for Shelley and Keats. I knew he had spent two years speaking Quechua and Spanish in Bolivia. He had been a U.S. Marine for four years and had won two blackbelts in karate. But until the explosion occasioned by seeing Doug’s books, I had him pegged as a small-town lawyer who had reverted to the provinces. While I, in contrast. . . .

The rooms of Doug’s law office contain, of course, those leather-bound books in glass-fronted cases meant to lend a sense of prosperity and sagacity to their owners. There are shelves and shelves of law books, various tools of the trade. The rest of the books, however, testify to intellectual curiosity of the best sort. Most of them have obviously been read (excluding a pristine copy of Heidegger’s Being and Time). There is a long shelf of books about Navajo language and culture. Several shelves of military his tory. Books about knots. Dozens of books about knots! Innumerable field guides to birds and animals. Entire bookcases devoted to philosophy and theology. A dozen translations of the Bible. Mormon books sprinkle the shelves, including 22 volumes of the Journal of Discourses, balanced by Meister Eckhart and St. John of the Cross and Thomas Merton and Martin Buber and Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian. There is lots of poetry. Shakespeare in abundance. Dictionaries galore: Spanish, Spanish/English, Spanish/English Legal Dictionary, Spoken Spanish, Navajo/ English, French/English, Latin Verbs, a reverse dictionary, a poet’s dictionary, a usage dictionary, Bible dictionaries, a bibliophile’s dictionary, literary terms, the Oxford English Dictionary, law dictionaries, dictionaries of quotations, crossword-puzzle dictionaries, dictionaries of etymology, and a whole raft of thesauruses. Armed with such books, Doug has written three dissertations: one for a doctorate of juridical science in taxation at the Washington School of Law, and two for doctorates in theology and ministry at the Faith Christian University.

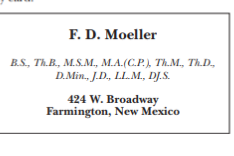

“Tyra says I’ll do anything for a certificate,” Doug told me. “Look at my card.”

F. D. Moeller

B.S., Th.B., M.S.M., M.A.(C.P.), Th.M., Th.D.,

D.Min., J.D., LL.M., DJ.S.

424 W. Broadway

Farmington, New Mexico

“Holy shit!” I said.

And it’s not all academic. Tyra dug out dozens of film reviews in the local paper, a set of poems published in a weekly column, and numerous “Guest Commentaries” by “F. Douglas Moeller, a Farmington attorney and poet” or, alternately, “a Farmington attorney and writer.”

This man in front of the adult Sunday School class in the Farmington Third Ward, this man with the gentle mien and soft, precise voice, this father of four and advocate in various tribal and state and regional courts, this collector of knives and guns and canes and masks and books, this provincial friend of mine is no provincial.

The part of the Book of Mormon Doug is teaching today raises interesting questions related to the text—why, for instance, does Jesus quote the King James translation of Isaiah, or what about the multiple Isaiahs Biblical scholars can identify?— but for the most part, members of this class want direction for their lives, succor for their wounded souls, reassurance that they are God’s children. That’s exactly what they get. Doug asks for any last questions or comments, then bears his testimony as to the truthfulness of the gospel.

While someone prays I remember Snyder’s reference to “short-haired joy” and think, of the members of this American church, that “I could almost love you again.”

12 November 2012

It’s ten degrees Fahrenheit when I begin my drive up the can yon, one degree as I drive through the snow-bound little mining town of Rico, ten degrees again when I drive into Telluride, busy with preparations for the ski season.

I spent the afternoon and night with my sister Carol at her home in Dolores, Colorado. When I arrived she was not long home from church, a place and a people that sustain her in this isolated little town. She greeted me warmly with chocolate-chip cookies right out of the oven. She’s as beautiful as she was before her accident. She described the veterans’ appreciation assembly her fifth-grade students will help with today. They have each interviewed a different veteran and have written three drafts of a short essay about the experience. They are lucky, I think, to have this intelligent and vital woman as their teacher. Carol gets two beers out of the refrigerator for Luther and me. She serves us a tasty plate of spaghetti with sausage and a side dish of salad.

When I called her to arrange the visit, Carol asked me “What’s up?”

“I’m calling to urge you to vote for President Obama,” I joked.

“I already sent in my early ballot,” she answered.

Driving northeast from Telluride, the snow rapidly disappearing, I listen to Mose Allison sing a Duke Ellington/Bob Russell song whose refrain has always puzzled me: “Do nothing ’till you hear from me / And you never will.” I listen closely to Allison’s brilliantly lax, behind-the-beat, swung performance of the story of separated lovers and the rumors that threaten to end the relationship permanently (“If you should take the words of others you’ve heard, / I haven’t a chance”). He sings of new experiences (“Other arms may hold a thrill”) and yet, paradoxically, professes enduring faithfulness: “Do nothing ’till you hear it from me / And you never will.” “It”—missing in the lines that perplex but present in an emphatic final line—would be the admission that he is untrue in his heart and that he no longer loves her. She will never hear that, he sings, because he will never speak it. (She, by the way, may decide she has had enough of this perhaps true and certainly troubled relationship, but that’s another story.) Love is complex. And perplexing. And swung.

I think this conflicted and heartfelt song might be a good number for my funeral. We sang “Ere you left your room this morning, did you think to pray?” for my father’s.

In Paonia I find the little house we lived in until I was five and then eat lunch in a downtown diner. I tell the waitress I lived in the log house, the one just up the street, when I was four years old. That was a long time ago, she says. It seems like yesterday to me—the memories are not timebound—but I agree with her on principle. Sweet potato fries and a Reuben sandwich flavor another reading of Snyder’s poem. He leaves Farmington “under the tough old stars,” girding himself for “What is to be done.”

I barrel along the still ecstatic highway to Green River, come back to myself on the northbound highway between the San Rafael Swell and the Bookcliffs, and finally, after descending the dangerous highway snaking down Spanish Fork Canyon, with real work still to be done, ease down the dark driveway from which Lyn has shoveled a foot of heavy snow.

Home again.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue