Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 4

Heretic and the Inversion of the Mormon Endowment

The opening credits of Heretic immediately immerse the viewer in mystery, as the title appears above a series of cryptic glyphs: 𐐐𐐆𐐊𐐆𐐓𐐌𐐕. To those steeped in Mormon lore, these symbols spell “Heretic” in the Deseret alphabet, a nineteenth-century script devised by early Church leaders.[1] These characters, however, serve not only as a nod to Mormonism’s quirky past but also an initiation into a world of symbols, sigils, and hidden meanings.

Written and directed by Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, Heretic is a psychological thriller that follows Sister Paxton (Chloe East) and Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher), two young missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At its surface, Heretic is a scary movie: the missionaries are sent to a remote area where they become entangled in the strange and unsettling world of Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant), a charismatic yet sinister figure. Reed’s sprawling, labyrinthine home becomes the site of increasingly bizarre and disturbing encounters that not only challenge the missionaries’ faith but threaten their lives. As they navigate the ominous halls and hidden chambers, they are forced to confront their deepest fears, ultimately unraveling the terrifying truth behind Reed’s intentions.

Beneath its chilling narrative, however, Heretic operates as a veiled metaphor for spiritual descent. While the film overtly engages with the monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, its symbolic language is steeped in occult and esoteric traditions. Additionally, by opening with arcane Mormon script, Heretic situates both the religion and its narrative within a broader mystical and symbolic context, challenging the archetypal pattern of spiritual ascent found in early Gnostic Christianity, various Western esoteric traditions, and modern LDS temple rituals.

This essay will begin by reviewing the narrative of Heretic, then introduce some of the key symbols and motifs found in Western esotericism—such as astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah, and sacred geometry—that inform the film’s exploration of ascent and descent. By examining these symbols, we can view the characters’ journeys as a modern parable and an inversion of traditional spiritual ascent. Finally, a comparison with the LDS endowment ritual will reveal how Heretic inverts the LDS temple’s dimensional and symbolic instruction on the soul’s journey through the afterlife, illuminating the esoteric divine feminine and shedding light on the deeper mysteries at play.

Heretic as Textual Narrative

Heretic unfolds a haunting narrative that blends unsettling imagery and reflective thematic exploration, immersing viewers in a tale of faith, manipulation, and transformation. Centered on two sister missionaries and their encounter with the mysterious Mr. Reed, the story reveals a layered progression of struggle and revelation, where religious rituals and cryptic symbols guide the characters through a maze of spiritual and existential challenges. This section will provide a summary of Heretic’s expository narrative, offering a clear account of its key events and character arcs, before delving deeper into the symbolic analysis that unpacks the film’s deeper meanings.

Act 1: Initiation

The story begins when Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes are caught in a storm and take refuge at the home of Mr. Reed. Reed welcomes them inside with an odd hospitality, claiming his wife is in the next room baking a blueberry pie. After he nonchalantly mentions that the house is encased in metal, he and the missionaries converse, and Reed’s questions and statements become increasingly uncomfortable, challenging the sisters’ religious convictions. The two women quickly realize that they are trapped—when they attempt to leave, they discover that the front door is locked, and their phones have no signal. This sense of entrapment marks the beginning of their psychological ordeal, setting the stage for their descent into Reed’s disturbing world.

Act 2: The Adept Gains Wisdom

Reed leads the missionaries deeper into his home, eventually bringing them to his chapel. Here, he presents a bizarre lecture on the nature of religion, suggesting that all religious systems are simply variations of one another. He introduces them to a series of unsettling choices, offering them two doors: one marked “Belief” and one marked “Disbelief.” After their initial hesitation, the missionaries are horrified to discover that both doors lead to the same terrifying destination—a dungeon-like space where they encounter a woman who consumes a poisoned pie and dies. Reed claims the woman is a prophet of God and that they will witness her resurrection. When the woman does “return to life,” she describes an afterlife that seems eerily similar to common near-death experiences. Sister Barnes challenges her account, expressing skepticism over the familiar narrative. In response, Reed kills Barnes, assuring her that she, too, will resurrect.

Act 3: Climax and Transformation

As Barnes lies bleeding out, Reed removes a metal object from her arm, claiming it is a microchip that proves the world is a simulation. Paxton, in a moment of clarity, recognizes it as a contraceptive implant, realizing that Reed has orchestrated the entire scenario to manipulate and control them. In a terrifying revelation, Paxton uncovers a hidden chamber containing emaciated women in cages—victims of Reed’s twisted house. This discovery leads her to the horrifying conclusion that Reed views religion and spirituality as tools for domination.

In a final confrontation, Paxton stabs Reed with a letter opener and he later pierces her abdomen with a box cutter. As both bleed in the basement, Paxton prays for solace, admitting that she knows prayer is ineffective but finds it beautiful to pray on other people’s behalf. Just as Reed prepares to finish her off, Barnes, still alive despite her earlier death, kills him with a plank of wood before succumbing to her wounds. Paxton, now alone, escapes into the snowy landscape. As she looks at her hand, she discovers a butterfly resting on it. But just as quickly as it appears, the butterfly vanishes, leaving Paxton alone in the desolate winter world.

Revealing the Mysteries: Key Clues and Cues from the Western Esoteric Tradition

Heretic includes many of the symbols and themes found throughout various currents of Western esotericism. The phrase “Western esoteric tradition” is a broad term used to encompass an array of mystical, philosophical, and occult practices that have developed over centuries, often in contrast to mainstream religious or scientific thought.[2] Comprised of diverse practices, from mystical traditions like Kabbalah and Hermeticism to philosophical systems such as Neoplatonism, Western esotericism is not a single unified system, though many of its currents share a common focus on uncovering concealed truths about the divine, the cosmos, and the nature of reality. This section will provide background on some of the traditions that make up modern esotericism, highlighting some of the key symbols and beliefs that are useful in understanding Heretic as a modern parable.

A. Temple and Cosmos: Themes from Gnostic Texts

Gnosticism[3] explores a spiritual framework characterized by four key elements: (1) the distinction between the ultimate, unknowable God and the imperfect or malevolent creator-god; (2) the depiction of a divine realm (Pleroma) from which humanity’s spiritual essence originates, including the myth of Sophia (“Wisdom”), whose fall precipitates the material world’s creation; (3) humanity’s entrapment in an earthly condition of ignorance and death, remedied by the revelation of gnosis delivered by a heavenly savior; and (4) the enactment of salvation through communal rituals that affirm the liberation of the divine spark within.

In Gnostic cosmology, the unknowable God (often called Bythos, Father, or Monad) embodies the primal unity from which all creation emanates. The lesser beings, or Aeons, are not fully autonomous entities but symbolic manifestations of the divine fullness, comprising the Pleroma alongside God. The myth centers on Sophia, the lowest Aeon, who creates the Demiurge (also known as Yaldabaoth), a flawed and ignorant being, through a misguided attempt to act independently of the Father. The Demiurge, mistaking himself for the sole creator, fashions the material world and enforces his dominion with the aid of Archons, entities that perpetuate humanity’s ignorance. Despite this, Sophia imbues humanity with a “divine spark” (pneuma), an aspect of divinity that can be awakened. The savior figure—often the “Living Jesus”—descends to reveal Sophia’s fall, expose the illusory nature of the Demiurge’s world, and guide humanity toward gnosis, the salvific knowledge that reunites the divine spark with its transcendent source.

The First and Second Books of Jeu are Gnostic texts preserved in the Bruce Codex, discovered in 1769 and likely dating to the fourth or fifth century CE, though their content is much older.[4] These texts serve as mystical manuals for spiritual ascent, detailing the soul’s journey through cosmic realms to attain eternal unity with the divine. The Books of Jeu are often associated with the later Pistis Sophia, which incorporates concepts from the Jeu texts.[5] In the first book, the “living” Jesus addresses his apostles, urging them to transcend the material world through secret knowledge that enables them to navigate the “Treasury of the Light”—celestial chambers guarded by spiritual beings called Watchers. Through a series of illustrations and topographical maps, the text outlines a cosmic structure emanating from the true God and provides diagrams, seals, and mystical instructions for passing through these treasuries, ultimately leading to an eternal, celestial realm.[6]

As the soul ascends along this journey, it must navigate hostile lower Aeons inhabited by malevolent Archons. To bypass these entities, the soul employs seals, divine names, and secret ciphers.[7] The Second Book of Jeu (2 Jeu) introduces a series of rituals—baptisms of water, fire, spirit, and the removal of archonic evil—necessary for progressing through the chambers. It maps the soul’s journey through twelve Aeons, culminating in the realm of the primal trinity. This is an adaptation of the highest trinity described in texts such as the Apocryphon of John: the Great Invisible Spirit, Barbelo, and the Unbegotten One, representing Father, Mother, and Son. The Apocryphon of John explains that Autogenes, the Self-Begotten One, is brought into being through the union of the Invisible Spirit and Barbelo, who “became the womb of everything, for it is she who is prior to them all.”[8]

This framework underscores the Gnostic emphasis on cosmological structures and the soul’s progression toward reunification with the divine. The Father, Mother, and Son trinity symbolizes the interplay of creation, emanation, and spiritual completion, guiding the soul’s journey through the Aeons toward ultimate enlightenment.

B. Mingling Myths and Magic

Gnosticism and its texts, including the Books of Jeu and Pistis Sophia, emerged from the cultural and spiritual syncretism of late antiquity. This era witnessed the blending of Greek philosophy, Egyptian cosmology, Hebrew mystical traditions, and nascent Christian thought, creating fertile ground for the development of both Gnostic texts and the corpus comprising the Greek Magical Papyri (abbreviated “PGM” from the Latin “Papyri Graecae Magicae”).[9] The PGM, a collection of texts from Greco-Roman Egypt dating from the second century BCE to the fifth century CE, were primarily discovered in Thebes and acquired by European institutions in the nineteenth century.[10] Written in Greek, Demotic, and Old Coptic, they reflect a deeply syncretic cultural environment where Greek, Egyptian, and other traditions intertwined.[11] Their content integrates deities, rituals, and magical practices from multiple traditions, like Jewish Merkabah mysticism, which describes ascents through celestial palaces.[12]

Both the Gnostic texts and the PGM share similarities with Egyptian funerary texts, such as the Book of the Dead, which guides souls through guarded regions of the afterlife.[13] Ancient Egyptian hry-tp (lector priests) also possessed a rich understanding of spiritual ascent, performing rituals at temples like those at Karnak and Abydos, enacting the soul’s passage through the Duat, the Egyptian underworld, where it undergoes trials and purification before reaching the realm of the gods.[14]

Central to these traditions and practices is the preoccupation with spiritual ascent and the manipulation of cosmic forces. The Books of Jeu, the PGM, and Egyptian funerary texts make extensive use of similar sacred names and magical words (voces magicae), and from them, new traditions emerged, derived from a synthesis of Greek, Coptic, and Hebrew traditions.[15] These texts emphasize divine names, esoteric rituals, and invocations to gain power over spiritual realms and to facilitate interaction with divine forces. While the Books of Jeu focus on detailed cosmological hierarchies and the soul’s ascent through celestial spheres, the PGM incorporate a wider range of magical applications, including love potions, wealth spells, and other rituals, alongside practices aimed at divine communion and spiritual empowerment.

Themes of sacred names, syncretic spirituality, and direct engagement with divine forces in the Gnostic scriptural texts, and the practical magic of the PGM, profoundly influenced later esoteric systems. The blended elements of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman religious traditions offered rituals and invocations meant to harness supernatural forces and attain personal transformation. This period laid the foundation for later developments in Western occultism, including the belief in an underlying, secret wisdom accessible to initiates.

C. Magic and Early Modernity

From these philosophical and religious currents, esotericism in the West evolved significantly during late antiquity, as Christian mysticism began to merge with Hermeticism. Emerging in the second and third centuries CE, Hermeticism is a philosophical and spiritual tradition rooted in the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a legendary figure who blends elements of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.[16] Both Hermes and Thoth are deities associated with wisdom, communication, and the occult, and in Hermeticism, they symbolize the union of Greek and Egyptian thought, particularly regarding knowledge, magic, and the divine.[17] Central to Hermeticism was the belief in the divine ordering of the cosmos and the potential for human ascent through knowledge, a concept that influenced later esoteric traditions.[18]

However, as the Christian Church rose to power, it sought to centralize religious authority and suppress competing beliefs. Non-Christian, unorthodox, and esoteric traditions, such as Gnosticism, Hermeticism, and paganism, were often deemed heretical.[19] These traditions, which emphasized personal revelation and hidden knowledge, came into direct conflict with the Church’s insistence on orthodoxy and the public transmission of doctrine. Consequently, many esoteric practices, texts, and ideas were driven underground. Those who continued to pursue such knowledge risked persecution, and as a result, esoteric knowledge became concealed, or “occult”—from the Latin occultus, meaning “hidden.”

This hidden tradition did not vanish entirely, however. As the ancient world gave way to the Middle Ages, esoteric thought became intertwined with Christian mysticism, Kabbalistic teachings, and alchemical traditions, motivating “not simply a matter of establishing intellectual harmonies, but rather the implication that these traditions sprang from a single, authentic, and divine source of inspiration, thus representing the branches of an ancient theology (prisca theologia).”[20] The Kabbalistic revival in the twelfth century, influenced by earlier Jewish mysticism and Christian theological reinterpretation, brought about an understanding of divine names and sacred geometry, which persisted into the Renaissance.[21] Alchemy, initially practiced as an art of transforming metals into gold, soon expanded into a spiritual discipline with the goal of personal transformation and the pursuit of the philosopher’s stone.[22] During this time, figures such as Paracelsus (1493–1541) integrated Hermetic principles with medical theory, seeing alchemy as a means of spiritual and physical healing.[23]

In the early seventeenth century, the Rosicrucian movement emerged as a fusion of Hermeticism, alchemy, and Christian mysticism.[24] The Rosicrucian manifestos (1614–1617), attributed to figures like Johann Valentin Andreae, propagated a vision of a secret brotherhood dedicated to spiritual enlightenment and scientific discovery, blending mystical and scientific thought.[25] This movement had a profound influence on the intellectual milieu of Europe, sparking a revival of interest in esoteric knowledge.[26]

The Renaissance was also the era of prolific magicians and occult philosophers, such as Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who reintroduced Platonic and Neoplatonic ideas, emphasizing the relationship between human beings, the cosmos, and divine realms. John Dee, the famed mathematician and astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I, blended alchemy, astrology, and mysticism in his quest for divine knowledge, using angelic communication to bridge the gap between the material and the spiritual.[27]

By the eighteenth century, much of the intellectual energy of Western esotericism had shifted toward freemasonry and Rosicrucian-inspired secret societies.[28] These movements, while sometimes oriented toward more social or political agendas, maintained a deep engagement with esoteric symbols, rituals, and the search for spiritual enlightenment. The Enlightenment brought some skepticism toward these traditions, but certain intellectual circles, led by figures such as Éliphas Lévi and the occult revivalists of the nineteenth century, carried the torch.[29]

The early nineteenth century saw the rise of spiritualism, which drew heavily on earlier esoteric traditions. This movement, which flourished in both Europe and the United States, emphasized communication with spirits through mediums and seances. Spiritualism was partly an outgrowth of the fascination with alchemy, magic, and theosophy and was characterized by a belief in the afterlife and the ability of the living to interact with the dead. Figures like Franz Anton Mesmer, who developed the theory of animal magnetism (later known as mesmerism), used psychic energy to heal and influence others, introducing a new form of magic grounded in the human mind and body.

Similarly, prominent leaders and practices of spiritualist movements, from the Fox sisters in New York to the seances of mediums like Andrew Jackson Davis, emphasized communication with the dead and the exploration of unseen spiritual realms. These currents contributed to the development of the so-called “psychic highway,” a region of esoteric belief and magical practice running through New England in the early nineteenth century.[30]

D. Mormonism and the Magic Worldview

Into this milieu, on the winter solstice of 1805, the prophet Joseph Smith was born.[31] In a way, his life can be seen as reflecting a progression through stages or degrees, beginning in Palmyra, New York, as his engagement with folk magic, treasure-seeking, and biblical prophecy marked his search for divine mysteries.[32] In Kirtland, Ohio, Smith constructed his first temple, formalized sacred rituals like the washing and anointing, and established the School of the Prophets to explore theology and mysticism, paralleling esoteric traditions of spiritual mastery.[33] Finally, in Nauvoo, Illinois, Joseph introduced the temple endowment and eternal sealing ordinances, which symbolized spiritual ascent and unity, bridging the material and divine.[34] The Nauvoo Temple, with its sacred symbolism and transformative rituals, epitomized Joseph’s culmination as a spiritual leader and his ability to guide others toward higher realms of understanding. Indeed, “Joseph Smith lived a richly symbolic life—a ritual life, if you will.”[35]

Smith’s work with the Book of Mormon and his translation of the sacred text via seer stones and divine visions parallel the practices of earlier occultists who sought hidden knowledge through mystical and spiritual means. Occult historian Peter Levenda observes that Mormonism arose from “the same root texts . . ., the sorcerer’s workbooks of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.”[36] Through his visionary work, Smith situates himself within the broader Western esoteric tradition, blending Gnostic principles with a uniquely American religious framework.

Codes and Keys: Language, Symbols, and Semiotics

Although Smith didn’t create the Deseret alphabet used in Heretic’s opening title, it was originally conceived as part of his church’s utopian effort to restore linguistic and spiritual purity. The alphabet was rooted in the Mormon belief that language had degenerated from its original Adamic form, the sacred tongue spoken by God to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.[37] For Joseph Smith, the Adamic language represented more than an intellectual curiosity; it was a pathway to recovering divine truths and unlocking latent spiritual power.[38] This pursuit echoes a recurring theme in Western esotericism: the quest for a sacred language capable of unlocking divine mysteries.

The early Mormons’ pursuit of linguistic purity parallels other esoteric traditions, notably the work of the Elizabethan magus John Dee and his scryer Edward Kelley.[39] Dee, in his efforts to communicate with angels and access higher realms of knowledge, used scrying stones to receive what he believed to be an ancient alphabet, later dubbed Enochian—a celestial language said to have been revealed through angelic visions.[40] Like the Adamic language, Enochian was considered a divine tool, a means of restoring humanity’s connection to the ineffable truths of creation.[41]

This focus on language and its meaning connects directly to semiotics, the study of signs, symbols, and their meanings within cultural and social contexts.[42] In a semiotic framework, the interpretation of meaning assigned to different letters varies significantly depending on context, or in some cases, one’s level of initiation. Exoteric understanding—the outer, surface-level interpretation—offers a general meaning accessible to all. In contrast, esoteric interpretation delves into hidden, inner meanings reserved for initiates who have undergone specific spiritual training or rites: things that appear straightforward to the uninitiated may harbor profound significance to those versed in the tradition’s secrets.[43]

Heretic uses a vocabulary of symbols throughout its narrative, which culminates in an ambiguous ending that invites viewers to question what they have seen. Themes of faith, control, and the blurred boundaries between reality and illusion are left unresolved, leaving the audience to interpret the film’s rich tapestry of symbols on their own terms. This lack of resolution highlights the inherently subjective nature of art and symbolism, where meaning is shaped by individual perspective.

Through layers of symbols, Heretic not only critiques institutional power but also illuminates the shared currents between esotericism and Mormonism. Just as the characters in the film confront a labyrinth of signs, so too must viewers seek their own understanding of what these symbols represent. What follows is one interpretation of Heretic and its layered symbolism—a subjective exploration of the meanings that might lie hidden within.

Unlocking Heretic’s Mysteries

When you climb up a ladder, you must begin at the bottom, and ascend step by step, until you arrive at the top; and so it is with the principles of the gospel—you must begin with the first, and go on until you learn all the principles of exaltation. But it will be a great while after you have passed through the veil before you will have learned them. It is not all to be comprehended in this world; it will be a great work to learn our salvation and exaltation even beyond the grave.[44]

—Joseph Smith

In Gnostic traditions, Sophia’s journey represents the soul’s pursuit of divine knowledge, or gnosis. Her initial descent from the Pleroma into the material world, driven by a desire to comprehend the unknowable, leads her to fall through a veil of darkness and ignorance. This fall results in her entrapment within the material realm, symbolizing the soul’s entanglement in the physical world. Through repentance and the assistance of higher divine powers, Sophia embarks on a journey of redemption, gradually ascending back toward the Pleroma. Her ascent reflects the soul’s journey through the veil of material existence, striving to reconnect with the divine source. Thus, Sophia’s narrative illustrates the transformative passage from ignorance to enlightenment, culminating in the reunification with the divine fullness.

It is impossible to say with certainty whether the filmmakers intended for Heretic to align with the Gnostic Sophia myth, but as the following analysis demonstrates, these symbols are undeniably present throughout the film. By examining these symbols through the lens of various currents within the Western esoteric tradition, Heretic can be seen as a version—or iteration—of the Sophia myth, offering a modern retelling of its central tale. Whether deliberate or not, the presence of these symbols enriches the narrative, guiding the viewer toward a deeper understanding of the film’s exploration of faith, control, and the cycle of descent and ascent.

A. Act 1. Initiation

i) The Sacred and the Profane

The first act of Heretic introduces Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes, who are presented in a quiet, introspective moment on a bus bench. Sitting opposite an advertisement for condoms on the bench, they have an awkward yet sincere conversation about Paxton’s experience with a “porno-ographic” movie, which establishes a thematic foundation for the film—one that explores dualities, the sacred and the profane—and foreshadows the spiritual journey ahead.

Soon after, the missionaries ascend and descend a cement staircase, their steps deliberate yet habitual. This movement mirrors recurring esoteric themes of ascent, descent, and transformation. The imagery evokes the journey described in Pistis Sophia, a Gnostic text in which the soul descends into chaos and ascends through realms of light and darkness, ultimately striving for reunion with the divine. The missionaries’ practiced steps suggest a cyclical nature to their journey, hinting that this passage is not a new experience but part of a larger, ongoing spiritual process—and that, perhaps, they’ve done this before.

From this perspective, Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes embody archetypal roles that mirror the Gnostic myth of Sophia and the Redeemer. In Gnostic tradition, Sophia is the embodiment of wisdom who, in her quest for knowledge, descends into the material world, leading to the creation of the flawed physical realm. Similarly, Sister Paxton’s journey reflects a descent into a world of deception and darkness, where she confronts her own beliefs and the nature of reality. Her experiences challenge her understanding, mirroring Sophia’s fall and the subsequent quest for redemption.

Sister Barnes aligns with the Redeemer archetype. In Gnostic narratives, the Redeemer is a divine figure who descends into the material world to impart gnosis, guiding souls back to the divine realm. Sister Barnes embodies this role by offering insight and guidance to Sister Paxton, helping her navigate the challenges they face. Like the Gnostic Savior, Barnes is a figure of action and sacrifice, deliberately entering darkness to bring light and knowledge to those trapped in ignorance. She assumes the role of a protector and teacher for Paxton, and through her eventual sacrifice, empowers Paxton to overcome the illusions and forces that bind her. Through these characterizations, Heretic intertwines Gnostic themes, using the archetypes of Sophia and the Redeemer to explore profound questions of faith, knowledge, and the human condition.

ii) Revelation at the Crossroads

Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes walk their bikes toward an intersection—a literal and metaphorical crossroads—where they encounter three sorority sisters who impede their path.[45] Initially, the interaction seems lighthearted, with Sister Paxton spontaneously declaring, “Oh my gosh, I already love these girls.” The giggling girls surround the missionaries, asking them to pose for a photo, but the playful encounter takes a sharp turn. As the missionaries pose, one of the girls asks, “Is it true?” before another pulls down Sister Paxton’s skirt, revealing her temple undergarment. The three girls cackle as they ridicule her “magic underwear,” a cruel derision that forces Paxton into a moment of not just intense vulnerability but revelation.

The intersection now takes on a liminal quality, serving as a crossroads where Paxton’s journey, beliefs, and sense of self will be tested, challenged, and ultimately defined. In this way, the scene evokes the symbolism of Hecate, the witches from Macbeth, and the Moirai—Greek mythology’s three sisters of Fate, weaving these mythological traditions into a moment of spiritual and existential significance. Hecate is the goddess of magic, witchcraft, and the underworld who stands as the guardian of the crossroads—an archetype of transition and choice.[46] In Pistis Sophia, Hecate is described as a “triple-formed deity,”[47] highlighting her role as a figure of boundaries, offering multiple paths and possibilities, and as the Roman poet Ovid observed, each of her three forms presents a choice of different paths.[48]

Echoing the Fates, the three sorority sisters can be seen to represent the three stages of life: one spins Paxton’s thread by initiating the confrontation, another measures its length through the trial of ridicule, and the third, like Atropos, cuts through Paxton’s illusions, exposing the latent power and magic within her.[49] Together, they weave the threads of fate and free will, pushing Paxton toward a transformative choice that will redefine her path. The scene also recalls the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, who, like Hecate, act as agents of fate. The three “weird sisters” deliver cryptic prophecies that unravel the natural order, guiding Macbeth toward his inevitable end.[50] Likewise, the three sorority sisters at the crosswalk serve as symbolic agents of destiny, posing the question “Is it true?” as a riddle that hints at the larger, unfolding narrative.

iii) The Candidates Present

Following their encounter at the crossroads, the missionaries arrive at the home of Mr. Reed, one of several prospective investigators (and the only one without a first, i.e., “Christian” name). As they head up the path toward Mr. Reed’s house, it is shrouded by darkening skies that portend an impending storm. Sister Barnes locks the bike and places the key securely in her pocket before the sisters approach the arched entrance to the house. There, beneath the arch, they are greeted by Mr. Reed (think Christopher Hitchens, but more polite). The missionaries inform him that pursuant to mission rules, another woman must be present for them to enter the home. He initially responds with feigned confusion before inviting them in, assuring them that his wife is nearby, busy baking pie in the next room.

The missionaries’ approach to the arched doorway of Mr. Reed’s house echoes the symbolic arches of King Solomon’s temple and thereby, inversely, the nine circles of Dante’s Inferno. In Freemasonry, the Royal Arch tradition recounts nine vaulted chambers beneath Solomon’s temple, with the ninth containing the sacred name of deity.[51] The arch, in this context, functions as both a literal threshold and a metaphor for initiation, suggesting that the sisters’ crossing signifies entry into a place where they will receive instruction.

Mr. Reed’s living room is comfortably appointed and well-kept. Decorative statues of birds perch on a shelf: one bird is ascending, the other descending, with an owl at the center, its unblinking eyes observing. A spool of yarn rests in a basket on a nearby chair, and a cross-stitched “Bless this Mess” sign confirms the coziness. Mr. Reed leaves the young women alone while he checks on the pie, and they seat themselves on a sofa situated between two six-sided end tables. A third hexagon appears as a window behind them, where Sister Barnes notices a butterfly struggling against the glass. Mr. Reed returns with refreshments—two glasses of caffeinated cola, which the missionaries demurely decline. Though they toe a fine line, they choose to follow their religion’s Word of Wisdom.[52]

In a pivotal scene, Mr. Reed confronts Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes with a scathing challenge to their faith and the narrative they are sent to share. As Sister Paxton begins her earnest retelling of Joseph Smith’s vision and the restoration of the gospel, Reed interrupts, revealing that he already knows the story. Producing a well-marked Book of Mormon from his cabinet, he dismantles their confidence, citing controversial episodes from early LDS history, including Joseph Smith’s alleged affair with Fanny Alger, often regarded as a shadowy precursor to the Church’s practice of polygamy.[53] Reed’s barrage of questions and accusations cuts through Sister Paxton’s rehearsed fervor, forcing the missionaries to confront the complexities and imperfections of their faith. The moment leaves the sisters visibly shaken, exposing the vulnerability beneath their conviction and setting the stage for deeper questions about belief, truth, and redemption.

With the tension in the room rising, Reed moves deeper into the house. After inventing a reason to stay back momentarily, Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes exchange panicked glances and move toward the door, only to discover it is locked. Paxton twists the knob desperately, her movements growing more frantic with each failed attempt. Their bikes are also secured outside, but the key to the locks is in Barnes’s coat pocket—rendered useless now that Mr. Reed has taken their coats to another room. The realization sets in like a heavy weight: they are trapped. The locked door, an unyielding barrier, seems to mirror their entrapment in a situation far darker and more complex than either had anticipated.

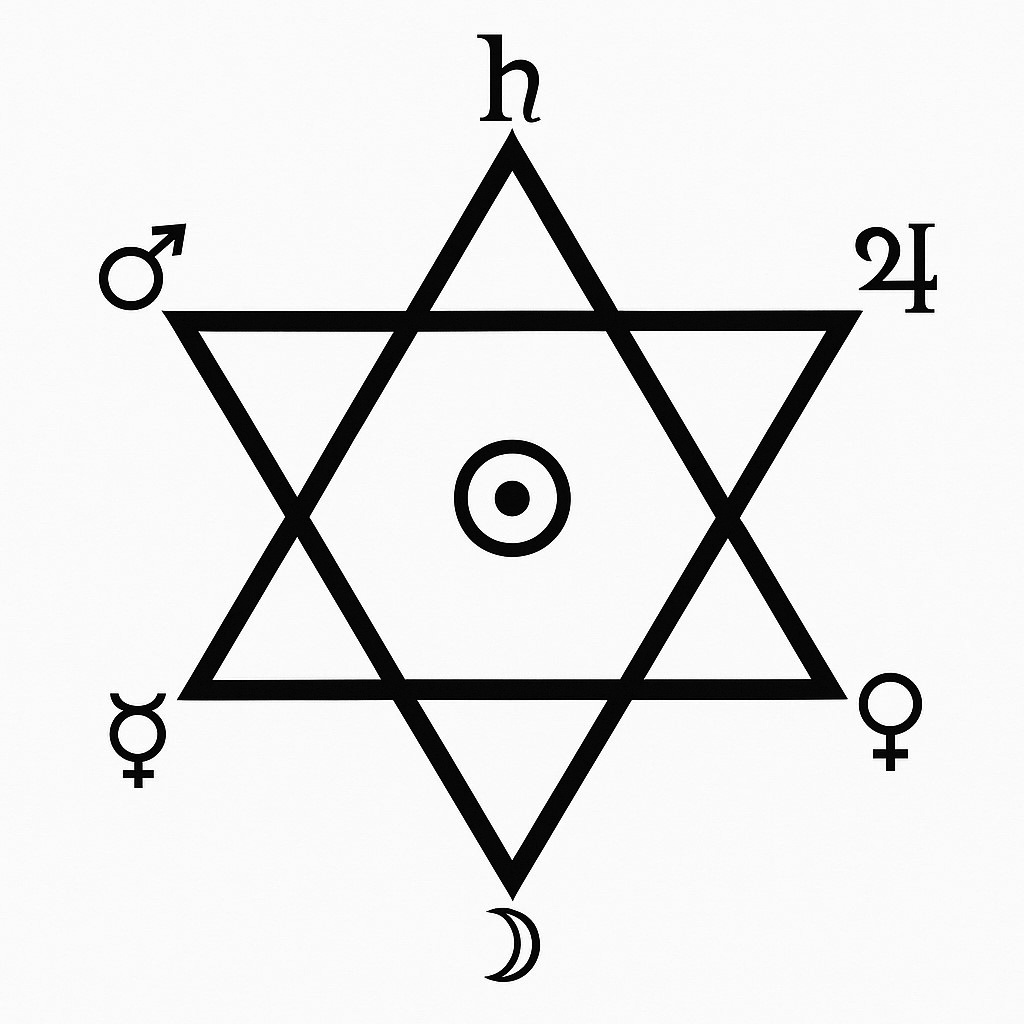

Figure 1. The Hexagram of Nature. J. Daniel Gunther. Initiation into the Aeon of the Abyss (Lake Worth, Fla.: Ibis Press, 2014), 38.

Within esoteric traditions, as well as in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the key—like the one Sister Barnes slipped in her pocket—functions as more than a practical tool. The act of holding or transferring a “key” often reflects the passing of authority and the responsibility to both reveal and conceal hidden truths. This symbolism aligns with Solomonic magic, where King Solomon’s legendary wisdom and control over spiritual forces are said to have granted him access to the universe’s secrets. Collected in grimoires like the Greater Key of Solomon and Lesser Key of Solomon, these practices symbolize the key as a tool to unlock spiritual gateways and command the hidden forces of nature.[54]

The three hexagons add another layer of esoteric meaning, representing equilibrium and transformation in sacred geometry. In Obeliscus Pamphilius (1650), Athanasius Kircher drew connections between the six-sided hexagram, metaphysical principles, and geometrical forms.[55] This symbol, long known as the Seal of Solomon, embodies balance, unity, and the intersection of the divine and the earthly. In esoteric symbolism, the hexagram holds profound significance, representing balance, harmony, and the interconnectedness of the universe, particularly in its association with King Solomon, known for his wisdom.

However, when multiplied or repeated, the hexagon can take on darker connotations, especially within occult traditions. Each hexagon is a six-sided shape, and the repetition of three hexagons—whether as physical objects or symbolic motifs—produces the number 666, commonly known as the “number of the beast” from Revelation 13:18.[56] Thus, in Mr. Reed’s home, the triad of hexagons subtly reinforces the idea that the missionaries have entered a domain governed by illusion, limitation, and a veiled, malevolent force.

The room’s elements—its locked door, ticking clocks, and geometric order—suggest the missionaries are caught within a constructed reality where time and space converge to demand transformation. Meanwhile, the butterfly trapped against the hexagonal window mirrors the sisters’ predicament, symbolizing their struggle to break free. The window, with its liminal placement, becomes not merely a portal but a representation of the paradox of their initiation: they cannot leave the space; they must go through it.

B. Act 2: The Adept Gains Wisdom

i) The Chapel: Sacred Geometry and Transformative Space

The missionaries descend a dark hallway, passing through shadows, into Mr. Reed’s chapel, where the space around them seems to shift and take on a new, otherworldly dimension. Heretic employs spatial dynamics as a symbolic tool, using distinctive shapes and geometry to evoke deeper metaphysical meanings. Through its intricate use of sacred geometry, the film converts physical space into a symbol for spiritual transformation, crafting a narrative grounded in the esoteric principle that space itself can act as a conduit for divine understanding.

The esoteric concept of sacred geometry holds a key to the chapel’s clues. This connection between space, geometry, and spiritual truth echoes a tradition that fascinated figures like King James of England, best known for commissioning the King James Bible.[57] His intellectual curiosity in the esoteric was shaped by scholars like Guy Le Fèvre de la Boderie, whose 1578 La Galliade, ou de la révolution des arts et sciences proposed that Gothic cathedral builders employed “sacred geometry” inspired by Pythagorean and ancient Hebrew mathematical traditions. Sacred geometry, in this context, was not merely practical but a way to unlock divine order, revealing cosmic truths embedded in the structure of the universe.

More recently, the twentieth-century alchemist Fulcanelli further explored this concept of space as a transformative agent in Le Mystère des Cathédrales (The Mystery of the Cathedrals).[58] Fulcanelli argued that cathedrals were far more than religious monuments; they were, in essence, books written on “pages of sculptured stone,”[59] encoded with the secrets of alchemy and the “great work.” The architectural designs of Gothic cathedrals were seen not just as impressive feats of engineering but as physical manifestations of hidden spiritual truths. Sacred geometry, and its accompanying power to transform physical space into a metaphysical conduit, was supposed to link the earthly realm with the divine.

According to these principles, physical environment becomes a medium for accessing higher knowledge, offering pilgrims and seekers a pathway to enlightenment. In this context, spaces such as the LDS temple or Mr. Reed’s house in Heretic can be understood as metaphysical pathways. Each space invites seekers to decode its mysteries, guiding them on a journey of awakening to the divine knowledge it holds. These sacred spaces become sites for the soul’s journey, where hidden truths await those who are willing to embark on the path of spiritual transformation, and new mysteries discovered by those with the eyes to see.

Ultimately, like pilgrims to cathedrals or participants in temple ceremonies, the missionaries find themselves not just surrounded by symbols but standing in one. The house itself, with its deliberately distorted geometry, religious iconography, and interplay of light and shadow, becomes a transformative space. The transition from the living rooms hexagons to the chapel’s three-dimensional cube suggests that this chamber, with its careful proportions and Saturnian symbolism, was not merely a chapel but a liminal space where the boundaries between the profane and the sacred are blurred, and the veil separating the mundane and the transcendent begins to dissolve.

This dimensional shift occurs as the rectangular door through which Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes enter assumes a different shape on the other side. The top of the door frame resembles the top half of a hexagon, though the bottom extends outward, expanding into a large room with pointed arches and ribbed vaults reminiscent of Gothic cathedrals. The room’s hexagonal footprint (evident later in the film) has its dimensions distorted by transepts bearing altars and religious iconography and the presence of two doors—one green and one purple—positioned on either side of an altar that stands at the fore of the apse.

The missionaries enter the warped symmetry of the chapel through a narrow, dimly lit library, its towering bookshelves packed with ancient texts, sacred writings, and esoteric tomes from myriad traditions. At the head of the room, the altar stands illuminated by two candles, their flickering light casting restless shadows across the space. Behind the altar, the chapel’s architectural design reveals a startling feature: the illusion of a three-dimensional cube, with Mr. Reed positioned at its precise center.

The haunting strains of “Just Like a Butterfly That’s Caught in the Rain” drift through the room:

Here I am praying,

Brokenly saying,

“Give me the sun again!”

Just like a butterfly that’s caught in the rain.[60]

Despite the metallic walls of the chapel’s exterior, an unexpected phenomenon occurs—water drips from above, a leak in the ceiling. The droplets collect in a sōzu, a traditional Japanese water fountain, which tips and resets in a steady, unchanging rhythm.

The dripping water serves as a symbolic bridge between the physical and metaphysical realms. In Christianity, the “living water” of Christ represents spiritual renewal and eternal life, flowing endlessly to cleanse and regenerate the soul.[61] In alchemy, water is the elemental force of dissolution, purifying and breaking down base materials to prepare them for transformation. The dripping water embodies both of these roles, suggesting the potential for transcendence while also marking the relentless passage of time—a passage that occurs within a space bound by the leaden constraints of material existence.

The sōzu—which cannot fully stop or contain the flow but merely slows it down—operates with a disciplined precision. Much like the ticking of the two clocks and the structured geometry of the metal-encased house, the sōzu serves as another clue to the presence of Saturn, whose symbolism permeates the narrative.

ii) Six Sides of Saturn

In the occult, the hexagon is intimately connected to Saturn, the planet of structure, discipline, and transformation.[62] This connection manifests in the natural hexagonal storm at Saturn’s north pole, a phenomenon that has fascinated both scientists and mystics alike.[63] Saturn, in alchemical tradition, is associated with lead, representing the unrefined, base material state that marks the early stages of both material and spiritual purification.[64] This association connects Saturn with the nigredo stage of alchemy, known as the “blackening” phase, during which decomposition and putrefaction occur. The nigredo represents the death of the old self, clearing the way for renewal and rebirth—much like the soul’s journey through darkness toward enlightenment. “Thus the Sol niger—Saturn—is the shadow of the sun, the sun without justice, which is death for the living,” writes Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz.[65]

For millennia (or at least since the Books of Jeu), the heavens have been regarded by some believers as a divine map, with the planets embodying higher powers and their movements reflecting cyclical currents of energy that subtly or profoundly shape human experience. Astrology and astronomy have been intertwined within the Western esoteric tradition since the ancient Sumerians first identified the seven classical planets: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.[66] These “wandering stars,” often referred to as deathless powers, have served as symbols of cosmic forces that influence both the material and spiritual realms.[67] This interplay between celestial and terrestrial realms—captured in the Hermetic axiom “as above, so below”—has guided the mystical seeker’s search for meaning, aligning the mysteries of the universe with the rhythms of earthly existence.[68]

Saturn is also connected to Kabbalistic traditions through the third sephirah, Binah, or “understanding.”[69] In the Tree of Life, Binah is associated with Saturn and represents the dark waters of creation—the primordial, flowing essence from which all existence emerges. As the supernal mother and queen, Binah embodies the feminine potency of divinity, standing in co-equal relationship with Chokmah, the sphere of wisdom and masculine creative force. Binah is therefore part of the Elohim, the great feminine aspect of God, in whose image both man and woman are formed.[70] Her connection to Saturn emphasizes discipline, limitation, and structure as essential aspects of creation, framing them not as mere restrictions but as the womb through which divine order manifests.

In this context, the black sun (sol niger) symbolizes the hidden light that emerges through this transformative process. Alchemical tradition holds that this stage of darkness, chaos, and confrontation with the shadow self is essential for attaining a deeper, more refined essence. Only by passing through the darkness—whether literal, emotional, or spiritual—can true enlightenment and transformation occur.

iii) The Veil Presents Itself

These symbolic elements reach their peak when, in a pivotal scene, the film cuts between characters, and the camera pans around the room. As the missionaries take in the surrounding details, they notice a striking alteration: the door through which they entered has vanished, replaced by a shroud of dark red—nearly black—curtains: a dark veil.

Here at the veil, Reed presents a lecture on the nature of religion, suggesting that all religious systems are simply variations of one another (think Christopher Hitchens, just more psychotic). Building his board game analogy, he likens religion’s iterations to Monopoly and its predecessor, The Landlord’s Game. He then presents Barnes and Paxton with the chilling choice between two doors: one for believers and one for non-believers. However, both doors lead to the same horrifying destination: a damp, hexagonal cellar, highlighting the futility of the choice and the inescapable cycle they are trapped within. This mirrors Gnostic teachings, where the illusion of choice is manipulated by the Demiurge, keeping souls bound to endless cycles of suffering and rebirth.

As the black curtain rises, revealing a female form reclining in luminous serenity, flanked by Shiva in his cosmic dance and twelve deities who echo the savior archetype, though confined within static frames—boundaries of tradition and doctrine. Amid twelve framed male deities, Sister Paxton must confront a new and demanding teaching. This is no longer a matter of rote belief or passive learning; it is an invitation to awaken to her own divinity. Sister Barnes dispels Sister Paxton’s doubts, and the pair chooses belief and descends the staircase into another hexagonal space.

iv) The Cellar

After some tension-building interactions between Mr. Reed and a diligent, if insensible, ward mission leader, Elder Kennedy (Topher Grace), Barnes is able to pull a match—a source of light—into the darkness. Earlier, when they first stepped into the basement, she had climbed onto a table like a sacrificial altar and dislodged a wooden plank, embedded with three nails. Right after, she hides the plank behind a pillar and passes a letter opener she retrieved earlier to Paxton, then creates a code phrase, “magic underwear,” to signal their plan. Paxton tucks the dagger into her pocket just as a shrouded figure carrying a lantern enters the room. The figure holds a pie, with the fire of the lantern flickering, illuminating the water, which is now trickling with more force than before.

Reed declares the woman is a prophet who will eat the pie—which he’s poisoned—and die; but, as a miraculous confirmation his is the “one, true religion,” she will be reborn. The missionaries perceive something that appears to Paxton to be the woman’s resurrection, though Barnes challenges Reed on what they actually witnessed.

Confronting Reed about the supposed “miracle,” Barnes starts to say the code phrase. However, as Paxton rushes toward Reed with the letter opener, Reed abruptly slices Barnes’s throat with a razor, the act swift and brutal, leaving her bloodied and vulnerable, marking the end of her guiding presence and the beginning of Paxton’s own inevitable transformation.

C. Act 3: Climax and Transformation

i) The Dungeon

As Barnes lies bleeding out, Reed coldly removes a metal object from her arm, declaring it a microchip that proves the world is a simulation. In a moment of clarity, Paxton recognizes the object as a contraceptive implant, exposing Reed’s elaborate deception. It becomes clear that Reed has orchestrated the entire scenario to manipulate and dominate them, using fear and illusion as his tools. Paxton’s growing awareness culminates in a horrifying discovery: a hidden chamber filled with emaciated women confined in cages—victims of Reed’s twisted power. This revelation cements Paxton’s realization that Reed views religion and spirituality not as paths to truth but as instruments of control and subjugation.

Here, Mr. Reed emerges as a type of Demiurge, the flawed and malevolent creator in Gnostic cosmology. Like the Demiurge, Reed traps souls within his illusory domain, obscuring their path to higher spiritual knowledge. His house, with its oppressive architecture and labyrinthine chambers, mirrors the material world described in Gnostic teachings as a deceptive construct—a prison of illusion designed to ensnare and mislead. The interplay of architecture, ritual, and character within the film’s first act also draws heavily on the esoteric symbols of Saturn, a planetary force associated with adversity, limitation, and ultimately transformation.

Earlier, in the living room, the film cryptically reveals that Paxton is the youngest of eight daughters, inviting an unsettling interpretation: the six caged women and the “prophet” who died after eating the pie may symbolize previous incarnations—or iterations—of Paxton herself, each born, trapped, and destroyed within Reed’s constructed reality. This framing aligns with the Gnostic view of the soul’s imprisonment in the Demiurge’s domain, forever cycling through futile existence without the liberating knowledge of gnosis. Paxton finds herself trapped in an ouroboric cycle—a Möbius strip of existence symbolized by the serpent devouring its own tail—engineered by Reed, who sustains his power through her perpetual entrapment.

In Jewish mysticism, the doctrine of gilgul describes the soul’s reincarnation as a process of rectification or spiritual growth, not too dissimilar from the Hindu and Buddhist cycle of samsara, where liberation (moksha) is the ultimate goal. Similarly, in Western esotericism, metempsychosis explores the soul’s movement between forms as a means of redemption or learning. Yet as Sophia’s fall from the Pleroma into materiality symbolizes humanity’s descent, her eventual redemption represents the possibility of spiritual restoration through wisdom. As a guide, she helps others return to the divine.

After Paxton has figured out Reed’s religion of control, she stabs him with the letter opener and tries to escape but isn’t successful because of the house’s disorienting architecture. Catching up with her, Reed stabs Paxton in the stomach with his box cutter. Not long after, Sister Barnes rises as if from the dead and delivers a decisive blow to Reed’s head with the wooden plank from earlier, giving Paxton an opportunity to escape. Sister Barnes’s self-sacrifice catalyzes Sister Paxton’s ultimate triumph. Her act mirrors the Gnostic savior who illuminates the path to liberation for others. Barnes’s temporary resurrection reflects divine intervention, underscoring the film’s exploration of reclaiming light from darkness. Together, these themes highlight the redemptive power of gnosis, sacrifice, and the pursuit of spiritual liberation

The arcs of Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes mirror Sophia’s archetypal journey. Their suffering and ultimate empowerment reflect the tales of descent and redemption found throughout the Western esoteric tradition: in rejecting Mr. Reed’s oppressive system, they reclaim their divine potential and serve as symbols of the feminine as a source of wisdom and spiritual liberation. Their defiance transforms them into redemptive figures, subverting the systems of control imposed by Reed and reclaiming the divine light.

In the climactic moments, Paxton whispers a prayer and finds an act of kindness within herself, enabling her to survive her ordeal through the indescribable power of prayer. She uses her own wits to solve Mr. Reed’s final puzzle, escaping through a narrow portal, a liminal space that hints at both physical and spiritual release. Heretic ends on an ambiguous note, leaving the audience with unanswered questions. The film resists full decoding, much like the enigmatic forces it portrays, demanding the viewer to grapple with its layered symbols and unanswered mysteries.

The Modern LDS Endowment and its Journey of Ascent

In addition to using LDS missionaries as protagonists, Heretic’s inversion of archetypal ascent journeys draws other parallels to Mormonism, particularly in the LDS temple endowment’s ritualized enactment of ascending from a fallen, earthly state to divine exaltation. The ceremony guides initiates through a symbolic ascent, paralleling the Gnostic tension between the ascent to spiritual realms and the descent into material bondage. Smith’s temple rites similarly transform the structure of the temple into a sacred space, where esoteric truths are encoded within ritual, architecture, and dimensional transformation.

President Russell M. Nelson explained that for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the temple is “a house of learning,” where individuals are taught “in the Master’s way,” which is “ancient and rich with symbolism.”[71] President Boyd K. Packer likewise taught that “if you will go to the temple and remember that the teaching is symbolic,” individuals will find themselves with “a vision extended” and their “knowledge increased as to things that are spiritual.”[72] This perspective reflects the notion that sacred spaces, such as the LDS temple, use symbolic instruction to convey hidden, spiritual truths that are accessible only to those prepared to receive them.

In Heretic, Reed’s home acts as an “anti-temple” and serves as a critique of the perversion of sacred spaces into tools of control and power. In contrast, the modern LDS endowment strives to preserve the integrity of sacred space as a site for spiritual enlightenment and personal communion with God. Paxton’s journey begins with the mockery of her “magic underwear” by strangers for whom she had just expressed innocent love. When she is stabbed at the end, it is in her navel, part of the body commonly associated with health and vitality. In the end, the “magic underwear” that earned the derision and scorn of the girls at the crosswalk may well save her. When she is stabbed, she survives (and awakens), reaffirming the transformative potential of true sacred experience.

Themes of power and redemption run through both the LDS endowment and Heretic, but with contrasting outcomes. The endowment’s “endowment of power” symbolizes spiritual empowerment through divine knowledge and enlightenment, often associated with the Tree of Life. Reed’s perverse “endowment of knowledge” seeks to subjugate participants through indoctrination. Yet, characters like Sister Paxton and Sister Barnes reclaim these symbols, embodying the true empowerment intended by sacred rituals. Their journey reflects a triumph over Reed’s counterfeit power, aligning with the transformative ideals of the endowment.

A. The Temple Ceremony

Designed to instruct participants about God’s plan for humanity, the LDS temple ceremony is a ritualized, transformative experience intended to deepen spiritual understanding and prepare participants for a closer connection to the divine. The endowment unfolds through several distinct stages, each associated with a specific room within the temple. These stages, through their symbolic language and ritualistic progression, chart a path of spiritual purification and ascension.

Participants embark on a spiritual journey through a series of symbolic rooms that reflect the Creation, humanity’s divine purpose, and the plan of salvation. This progression culminates in the celestial room, representing communion with God and eternal life. Each space fosters enlightenment, offering sacred teachings and opportunities for covenant-making.

By contrast, Heretic reimagines this structure with Mr. Reed’s “instruction room,” a distorted counterpart that indoctrinates participants into a twisted “religion of control.” Instead of leading toward divine understanding, Reed’s ritual emphasizes manipulation and despair, subverting the spiritual intent of such rites. This inversion underscores one of the film’s central themes: the corruption of sacred rituals to sustain oppressive ideologies.

The structure of Mr. Reed’s house inverts the symbolic principles and spatial progression of the LDS temple endowment ceremony, creating a distorted mirror of spiritual transformation. The film opens in Mr. Reed’s living room, the best room in his house, a stark reversal of the temple’s progression, where the room representing glory—the celestial room—comes at the end, symbolizing the culmination of spiritual ascent. Instead of moving toward greater light and understanding, participants in Reed’s chapel journey deeper into confusion and darkness, reflecting a deliberate subversion of divine order.

The film’s use of the black veil further emphasizes this inversion. In the temple, the veil signifies the boundary between mortal life and the divine presence, symbolizing spiritual ascent into God’s glory.[73] Reed’s black veil, however, represents the opposite: a descent into a shadowed, corrupted understanding. It denies participants access to transcendent truth, confining them within the material and mortal world. Each space within Reed’s chapel reflects this unsettling reversal, where the intended path of purification and enlightenment becomes a descent into spiritual disarray, twisting the sacred principles into their dark antithesis. Through these inversions, Heretic critiques the misuse of sacred rituals and the fragility of spiritual progress when corrupted by human influence.

Spatial symbolism plays a critical role in highlighting this subversion. The LDS endowment ceremony is an upward journey, symbolically ascending toward divine presence. Participants move from external purification (“washings and anointings”) through rooms that represent Creation, the Fall, and humanity’s spiritual progression, culminating in the celestial room. In Heretic, this ascent is reversed. Participants descend deeper into the earth, moving toward a literal and symbolic hell. The downward progression mirrors spiritual degradation, starkly contrasting the uplifting and aspirational nature of the temple journey. This deliberate reversal reinforces Mr. Reed’s authoritarian worldview, where domination replaces divine communion.

Similarly, the LDS endowment ceremony symbolically represents an ascent toward God’s presence, paralleling the Gnostic journey of spiritual ascent. Participants progress through symbolic stages—Creation, the Fall, and redemption—that culminate at the veil, a gateway to divine communion. This structured journey mirrors the Gnostic soul’s ascent through cosmic barriers to reunite with the divine Pleroma, emphasizing spiritual growth and preparation for eternal life. This structured journey emphasizes spiritual growth and preparation for eternal life.

In contrast, as discussed below, the anti-endowment in Heretic subverts this concept. Upon leaving the outer world and entering Mr. Reed’s prison world, Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton are seated in a room with a hexagonal window. The geometry of the hexagon holds rich symbolic significance within esoteric traditions, where it is often linked to the planet Saturn and its associated themes of structure, limitation, and adversity. The six-sided figure, appearing in nature through patterns like honeycombs and Saturn’s polar hexagonal storm, represents the interplay between order and chaos.

From an esoteric perspective, Heretic engages with archetypal themes of ascent and descent, light versus darkness, and the tension between liberation and subjugation. Reed’s descent into hell reflects an anti-endowment steeped in occult dualities: every act of creation or ascent has its shadow counterpart. This descent into chaos contrasts with Sister Paxton’s eventual empowerment, which embodies the esoteric ideal of self-realization and mastery over external forces.

B. Inverting the Sacred

The progression of rooms in the LDS temple ceremony mirrors an archetypal journey of spiritual ascent and enlightenment, structured to guide participants through layers of symbolic understanding. Beginning in the initiatory room, participants are symbolically cleansed and prepared for the sacred journey. They proceed to the creation room, where the formation of the world and humanity’s entry into existence are reenacted, setting the stage for themes of divine order. The garden room follows, evoking a state of innocence and harmony with God before the Fall. Participants then enter the world room, representing the trials and challenges of a fallen, sinful world. Ascending further, they reach the terrestrial room, a space of greater light and understanding, where spiritual progression culminates in preparation for passing through the veil. Beyond the veil lies the celestial room, symbolizing divine glory and union with God, and in some temples, the Holy of Holies serves as the sacred core of communion with the divine. This journey reflects a deeply Gnostic and esoteric narrative of descent, testing, and ascent, designed to transform the individual by guiding them from the profane to the sacred.

In Heretic, the rooms of Mr. Reed’s house stand as a dark inversion of this sacred journey, critiquing the misuse of spiritual authority and faith. The basement theatre, where Reed conducts his experiments, represents a perverse testing ground—a corrupted counterpart to the temple’s world room—where the labyrinthine structure serves to manipulate and break rather than refine and elevate. Ascending through the house, the occult chamber, filled with trinkets and a skull, echoes esoteric traditions but reduces their transformative potential to tools of power and control. At the center of the house lies the chapel room, with its makeshift altar and religious icons, symbolizing a disjointed, eclectic faith that binds rather than liberates. The design of the chapel, with Reed standing in a cube that echoes the hexagonal window from earlier, underscores the distortion of sacred geometry, transforming symbols of freedom and unity into those of confinement. Like the LDS temple, the structure of Reed’s house reflects a narrative of transformation, but in Heretic, it is deliberately corrupted to critique spiritual manipulation. Together, the temple and the house present parallel but opposing journeys, one seeking enlightenment and unity with God, the other highlighting the destructive potential of misused faith.

Conclusion

The LDS endowment offers a framework for transcendence. Its symbolic teachings—delivered through signs, covenants, and sacred tools like the compass and square—emphasize mastery and co-creation within the divine order. These symbols affirm the potential for individuals to transcend deception and embrace universal truths. Heretic critiques the corruption of such sacred, symbolic frameworks while also reclaiming their transformative potential through its protagonists’ resistance and triumph.

Ultimately, Heretic operates as a meditation on the tension between institutionalized religion and personal spiritual transformation. By subverting the structure and symbolism of the LDS endowment, the film critiques how rituals can be distorted to sustain power. However, it also celebrates the reclamation of spiritual agency, offering a counternarrative to oppression. Sister Paxton’s eventual empowerment and escape shatter Reed’s false veil, revealing its illusory nature and enabling her spiritual liberation.

Through its exploration of Gnosticism, sacred spaces, and Joseph Smith’s religious legacy, Heretic illuminates the universal quest for enlightenment and serves as a modern iteration of the Sophia myth. The collision of the sacred and the profane challenges viewers to consider how rituals, spaces, and individual journeys shape humanity’s search for transcendence, reminding us of the enduring relevance of Gnostic ideas in contemporary storytelling, whether revealed through sacred rites or just a night at the movies.

[1] “Deseret Alphabet,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), available online at https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/EoM/id/5669/; see also Richard G. Moore, “The Deseret Alphabet Experiment,” Religious Educator 7, no. 3 (2006): 63–76.

[2] This essay relies on the frameworks proposed by Wouter J. Hanegraaff and Antoine Faivre, which provide a comprehensive foundation for understanding the broad and varied landscape of Western esotericism. Hanegraaff defines Western esotericism as a form of knowledge that transcends conventional frameworks, offering a counterpoint to traditional religious or scientific discourses. Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). Faivre, in turn, emphasizes the intellectual principles underlying esoteric thought, such as the use of symbolism, correspondences, and the belief in hidden knowledge revealing spiritual truths. Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994).

[3] For this essay, “Gnosticism” is used primarily as a heuristic device rather than in reference to a particularly defined set of communities or beliefs. To this extent, the essay relies on and adopts Roelof van den Broek’s characterization of Gnosticism as a religious worldview centered on “gnosis,” an esoteric knowledge concerning the divine and human existence that offers salvation to its possessors. Rather than categorizing Gnosticism according to specific sects or historical movements, van den Broek focuses instead on the underlying emphasis on esoteric knowledge as the defining criterion. Roelof van den Broek. Gnostic Religion in Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[4] Erin Evans, The Books of Jeu and the Pistis Sophia as Handbooks to Eternity: Exploring the Gnostic Mysteries of the Ineffable, Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies, vol. 89 (Leiden: Brill, 2015); see also Hugh Nibley, “Prophets and Gnostics” and “Prophets and Mystics,” in Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Vol. 3: The World and the Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1987 [first published 1954]), 63–70, 98–107; Hugh Nibley, “One Eternal Round: The Hermetic Version,” in Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Hugh Nibley and Don E. Norton (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 379–433.

[5] Evans, The Books of Jeu and the Pistis Sophia as Handbooks to Eternity.

[6] Dr. Justin Sledge, curator of the “Esoterica” YouTube channel, has produced an informative video that was not only helpful in this essay but is an excellent introduction to the Books of Jeu. “The Only Illustrated Ancient Gnostic Manual of Mystical Ascent After Death – The Two Books of Jeu,” posted Mar. 24, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhGXgegKeSI.

[7] Evans, The Books of Jeu and the Pistis Sophia as Handbooks to Eternity.

[8] Apocryphon of John, 5.5–8.

[9] Hans Dieter Betz, ed., The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation: Including the Demotic Spells (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); see also Georg Luck, Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).

[10] The historical discovery of the PGM in the early nineteenth century coincided with Antonio Lebolo’s excavation of mummies and papyri from the same region. See Michael H. Marquardt. “Joseph Smith’s Egyptian Papers: A History,” in The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri: A Complete Edition, edited by Robert K. Ritner (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2013), 11; H. Donl Peterson, The Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 78–83. The Joseph Smith Papyri, which include “an ancient funeral illustration”—a resurrection spell—“for a deceased Egyptian man named Horus” (Marquardt, 61), became the basis for the Book of Abraham, and Smith’s acquisition of these artifacts represents a curious coincidence, if not a modern link, to these ancient traditions.

[11] Betz, The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation.

[12] Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Schocken Books, 1995), 40–79.

[13] E. A. Wallis Budge, ed., The Egyptian Book of the Dead (London: Penguin Classics, 2008); see also Mark Smith, ed., Following Osiris: Perspectives on the Osirian Afterlife from Four Millennia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[14] “Performed by priests as the technique of religion, Egyptian ‘magic’ cannot be opposed to religion, and the Western dichotomy of ‘religion vs. magic’ is thus inappropriate for describing Egyptian practice.” Robert K. Ritner, The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice (Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1993), 2.

[15] Arthur Versluis, Magic and Mysticism: An Introduction to Western Esoteric Traditions (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007).

[16] Clement Salaman, et al., trans., The Way of Hermes: New Translations of the Corpus Hermeticum and the Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2000).

[17] Florian Ebeling, The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times, translated by David Lorton (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2007).

[18] Roelof van den Broek and Wouter J. Hanegraaff, eds., Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998).

[19] Richard Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

[20] Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 9.

[21] Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism.

[22] Stanton J. Linden, ed., The Alchemy Reader: From Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[23] Charles Webster, Paracelsus: Medicine, Magic and Mission at the End of Time (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008).

[24] Lyke de Vries, Reformation, Revolution, Renovation: The Roots and Reception of the Rosicrucian Call for General Reform (Leiden: Brill, 2021).

[25] Frances A. Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972).

[26] Goodrick-Clarke, The Western Esoteric Traditions.

[27] Jason Louv, John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochian Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2018).

[28] Owen Davies, America Bewitched: The Story of Witchcraft After Salem (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 252.

[29] Goodrick-Clarke, The Western Esoteric Traditions, 184–85.

[30] Mitch Horowitz, Occult America: White House Séances, Ouija Circles, Masons, and the Secret Mystic History of Our Nation (New York: Bantam Books, 2009).

[31] D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, revised and enlarged (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998); John L. Brooke, The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Dan Vogel, “The Locations of Joseph Smith’s Early Treasure Quests,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 197–231.

[32] See Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View; see also Richrd Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Cultural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023); Lance S. Owens, “Joseph Smith and Kabbalah: The Occult Connection,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 117–94.

[33] Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005).

[34] Matthew B. Brown and Paul Thomas Smith, Symbols in Stone: Symbolism on the Early Temples of the Restoration (American Fork, Utah: Covenant Communications, 1997); David R. Crockett, “The Nauvoo Temple: ‘A Monument of the Saints,’” Nauvoo Journal 6, no. 1 (1994): 5–28; Kenneth W. Godfrey, “The Importance of the Temple in Understanding the Latter-Day Saint Nauvoo Experience: Then and Now,” Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lecture Series, no. 6, Oct. 25, 2000, available online at https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_lecture/5/.

[35] George L. Mitton, “The Book of Mormon as a Resurrected Book and a Type of Christ,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 392.

[36] Peter Levenda, The Angel and the Sorcerer: The Remarkable Story of the Occult Origins of Mormonism and the Rise of Mormons in American History (Lake Worth, Fla.: Ibis Press, 2012), 78; see also John R. King IV, The Faculty of Abrac: The Tradition, Training, and Techniques of Commanding Spirits (Lulu, 2021). King explores the lesser-known esoteric influences on Joseph Smith, highlighting his familiarity with apocryphal writings, noting that Smith not only possessed esoteric talismans but also engaged in treasure-seeking aided by spirits. According to King, Smith’s method of dictating the Book of Mormon, which involved mystical revelations received through scrying stones, parallels the practices of occult figures, claiming “his entire religion was dictated in a method reminiscent of John Dee and position[s] Smith within a broader tradition of esoteric mysticism” (King, 84). See also Massimo Introvigne, “The Beast and the Prophet: Aleister Crowley’s Fascination with Joseph Smith,” in Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism, edited by Henrik Bogdan and Martin P. Starr (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 255–84.

[37] Samuel Morris Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation: The Words and Worlds of Early Mormonism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 21–22. Brown notes that the language is called “Adamic” by convention alone; he proposes “Edenic as more accurate, since the language was spoken by all in Eden, not just the first man” (21).

[38] See Moses 6:5–6. The Book of Moses, produced by Joseph Smith in 1830, says that says Adam kept a book of remembrance “in the language of Adam” and that his children “were taught to read and write, having a language which was pure and undefiled.” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Book of Moses,” in The Pearl of Great Price (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981).

[39] If Dee and Kelley’s Enochian is the Monopoly of magical languages, Hildegard of Bingen’s Lingua Ignota could be its Landlord’s Game. Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), a German Benedictine abbess, mystic, and polymath, created the Lingua Ignota (“Unknown Language”) as part of her visionary works. This constructed language, comprising unique vocabulary and a corresponding alphabet, was intended for divine praise and spiritual expression. Hildegard described the Lingua Ignota as a holy tongue revealed to her in visions, reflecting her innovative theological insights and her belief in the unity of divine creation, while standing as one of the earliest known examples of a constructed language in Western history. Though the language and its purpose remain a mystery, some theorize it “may have been an attempt to reproduce the pure, virginal tongue spoken by Adam and Eve in paradise.” Barbara Newman, ed., Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 16; Barbara Newman, Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

[40] Deborah E. Harkness, John Dee’s Conversations with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

[41] Aaron Leitch, The Angelical Language, Volume I: The Complete History and Mythos of the Tongue of Angels (Woodbury, Minn.: Llewellyn Publications, 2010); Louv, John Dee and the Empire of Angels.

[42] Daniel Chandler, Semiotics: The Basics, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 2017).

[43] Patrick Dunn, Magic, Power, Language, Symbol: A Magician’s Exploration of Linguistics (Woodbury, Minn.: Llewellyn Publications, 2008).

[44] Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, compiled by Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1976), 348.

[45] The roles are credited as “Teenagers,” but the screenplay identifies them as “sorority girls,” i.e., sisters. See Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, Heretic, available online at https://a24awards.com/assets/Heretic-screenplay.pdf.

[46] Sarah Iles Johnston, Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate’s Roles in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature, American Classical Studies 21 (Atlanta: Scholar’s Press, 1990).

[47] Hecate “appears a great archon[ ] of the Midst, tormenting the souls of sinners.” She “is described as three-faced; this is in keeping with Greco-Egyptian magical tradition, which frequently depicts her as three-formed.” Evans, The Books of Jeu and the Pistis Sophia as Handbooks to Eternity, 118.