Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 2

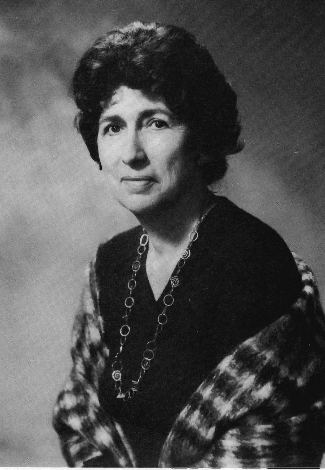

Fawn McKay Brodie: An Oral History Interview

The following is excerpted from a longer interview conducted by Shirley E. Stephenson as part of the Oral History Program at California State University at Fullerton, November 30, 1975.

Mrs. Brodie, to begin, I would like you to tell me about your early background.

As you doubtless know, my parents were devout Mormons and I was brought up in a small Mormon town of very great beauty in Ogden Valley which is just through Ogden Canyon and east of Ogden. There are three small towns there. One is called Huntsville and there is where my grandfather and grand mother, David McKay and Jeanette Evans McKay, built a house which is now over one hundred years old. Last summer [1975] we celebrated what would have been his one hundredth birthday, had he lived. He was born in 1875 in Huntsville, Utah. The children, grandchildren, and great-children gathered for this occasion. It was great fun. My grandfather was one of eight children. There were ten all together but two older sisters died of diptheria in an epidemic. So this was very much the ancestral home; a big, old farmhouse with fourteen rooms and no bathroom.

My father divided his time between city jobs—he was at heart a politician. He was, for a time, president of the Senate in the Utah State Legislature. He then had a job as chairman of the State Utility Commission, so we lived in Huntsville, which we loved madly, despite the difficulties of living in this ancient farmhouse which was hard to heat, hard to clean, but wonderfully spacious and a great place to grow up. There were barns, a creek where we, swam, and a river where we swam when we were older. It was an idyllic childhood as far as the freedom and the affection and the sense of belonging to a community was concerned. It was also very parochial.

How large was your family?

I was one of five. There were four girls and I was the second daughter. The son came in the middle.

How large is the family now, with grandchildren?

Well, there were fifty-six at the reunion. I think there are about sixty-four of us all together.

Would you continue about your family influence and the religious influence?

Well, we were all brought up as very devout Mormons, and I was devout until I went to the University of Utah. Then is when I first began to learn important things. I had no anthropology but I had psychology and sociology. I think most importantly—my field was English literature—what was really important, as I realize now looking back on it, was that one ceased, or one began to move, at any rate, out of the parochialism of the Mormon community. At least I did by being exposed to the great literature of the past. This was a very quiet kind of liberation; there was nothing very spectacular about it. There was no active trauma. It was a quiet kind of moving out into, what you might call, the larger society and learning that the center of the universe was not Salt Lake City as I had been taught as a child.

But this was slow, and it was not really until I went away to graduate school at the University of Chicago that I understood how much of a liberation the university experience in Salt Lake City had been, because then the con fining aspect of the Mormon religion dropped off within a few weeks. As I’ve said before, “It was like taking off a hot coat in the summertime.” The sense of liberation I had at the University of Chicago was enormously exhilarating. I felt very quickly that I could never go back to the old life, and I never did. Even though I loved going home, it was going back into the past.

My father really never understood the nature of my break with my past. I think he tried to, but it was always very painful for him. He was always pulling me, trying to pull me back into the Mormon community, the Mormon society, back into the brotherhood. But he couldn’t. I told him the university world was my world and not the church. He finally accepted it, but with a lot of pain because he was very devout and a Mormon preacher of considerable talent. He was rather high in the church hierarchy. As a matter of fact, he was, finally, what we call an assistant apostle and later his brother David became a president of the church, so the church was very important in the family life. My uncle was very much the family patriarch who dominated all of the McKay family, to an extraordinary degree, just like an old Chinese patriarch.

Was this David McKay?

David O. McKay.

What about your mother’s reaction?

Mother was a kind of quiet heretic which made it much easier for me. Her father [George H. Brimhall] had been nominally devout but as president of the Brigham Young University he had brought in people like G. Stanley Hall and John Dewey as lecturers, and philosophers and psychologists who were fascinated by the Mormon scene. He was a very open-minded man and a fine educator. Some of this rubbed off on my mother and so I say, “My grandfather was not a heretic, but his children were,” or rather some of them were.

Her heresy was very quiet and took the form, mostly, of encouraging me in a quiet way to be on my own. But that made for some family difficulties, too.

What about your brother and sisters?

Well, my brother is still a devout Mormon but my sisters are all, what we call, “Jack Mormons,” since they are still technically in the church but they are not active and they don’t go along with the Mormon dogma. They still count themselves Mormons.

Do you?

Oh, no. I am an excommunicated Mormon. I was officially excommunicated when the biography of Joseph Smith was written and published. About six months after publication, there was a formal excommunication.

Would you care to explain more about that?

I was excommunicated for heresy—and I was a heretic—and specifically for writing the book. My husband was teaching at Yale at the time and we were living in New Haven [Connecticut]. Two Mormon missionaries came to the door and presented me with a letter asking me to appear before the bishop’s court in Cambridge, Massachusetts to defend myself against heresy. I simply told them, or wrote a letter telling them, that I would not go because, after all, I was a heretic. So then I was officially excommunicated and got a letter to that effect.

This was because of writing the book No Man Knows My History?

This is right.

Were you allowed ample access to records and manuscripts when you were writing the book?

Almost all of the material in the book came from three great libraries. At the University of Chicago, where I was working after I married Bernard, there was really a great collection of western New York State history. By going through the material I was able to find out something about the sources of Joseph Smith’s ideas, particularly the ideas which went into the writing of the Book of Mormon. I finally ended up going to Albany, New York, where all the newspapers were kept which were published in Joseph Smith’s own hometown in Palmyra, New York. So I was able to read the newspapers he had read as a young man. This turned out to be an absolute gold mine! A lot of the theories about the American Indians being descendants of the Lost Ten Tribes and the descriptions of what were being found in the Indian mounds were in the newspapers. The speculation was there. That was extremely important as was the anti-Masonic material. The anti-Masonic excitement was very strong at that time. Then I went to the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. The New York Public Library has the best Mormon collection in the country outside of Salt Lake City.

I did go to the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at Independence, [Missouri], and I did go to the library of Salt Lake City for some periodicals, early Mormon periodicals that I couldn’t get anywhere else. I was permitted to see those, but I was not permitted to see any manuscript material.

Are those [church archives] open now? I read a comment indicating that it was believed that your book would open archival material.

It had just the reverse effect. The archives were largely closed to scholars after my book came out.

Was there a fear that someone else would do the same thing you did?

That’s right. I think I should be very exact in my statement. It is not quite true to say the manuscript sources were denied to me. I had been told that there was a diary of Joseph Smith in his own handwriting, written when he was in his early twenties. I knew one man at the Brigham Young University, who is now dead, who had seen it and read it. But when I asked to see it, I was told I could not see it. Then I had a very long, and very difficult interview with my uncle, David O. McKay. Afterward, he told me I could see the manuscript, but by this time the family situation had become so delicate that I felt that I would rather not take advantage of my uncle’s name to use this material. I wrote to him saying I would not ask for any more material and I never went back to the church library. So, technically, I was given access, but I didn’t use it. It was made very clear to me that it was an extremely difficult family situation, so that is the way I handled it.

Was this after you began a career in writing? Had you thought about this long before your days at the university?

Oh, I had always wanted to write fiction. I discovered after writing numerous short stories that this was not my forte. Then after I was married, my husband, who is Jewish and totally new to the Mormon scene, was very fascinated by it. In answering his questions, this stimulated the desire in myself to find out the roots and sources of what Joseph Smith’s ideas were. In any case, I started out not to write a biography of Joseph Smith but to write a short article on the sources of the Book of Mormon.

In my research in the University of Chicago library, I thought I had found some answers. But, having done that, I had by that time done enough research to realize first of all there was no good biography of Joseph Smith and also I had to answer the questions myself. If the Book of Mormon came out of his own background in western New York, which he insisted came from golden plates, then what kind of man was this? The whole problem of his credibility, I thought, was crying out for some explanation. So then I moved into the much more difficult task of writing the biography. It was a piece of detective work that I found absolutely compelling. It was fantastic! I was gripped by it. I spent seven years doing the research and writing and I was fascinated the whole time. I was baffled by the complexities of this man and remained somewhat baffled even after the book was finished. It wasn’t until fifteen or twenty years later when I had done a lot of reading in psychiatric literature that I felt I had some more explanations. I have tried to put a little bit of this in the supplement which came out in the second edition, in 1971.

If I were to write it over again, knowing what I know now about human behavior, I think I would do a better job; but on the whole, it holds up quite well. I am really proud of the book and stand by everything in it.

What did you include in your supplement that you didn’t have in the original edition?

Mostly, it was a matter of trying to let the reader know what had happened in the Mormon research in the twenty to twenty-five years since the first edition. Some very important material had come out of the church library about the so-called “first vision” of Joseph Smith. It turned out there are three versions of the first vision, each one quite different from the other. This bore out my theory of the evolutionary character of the first vision.

Then there were some very important new data about the holy book called the Book of Abraham. I had been told, and everybody thought that the papyri which Joseph Smith is supposed to have translated of the Book of Abraham had been burned in the Chicago fire. It turned out that it had not been, that Emma Smith had sold it and it had ended up in the New York Metropolitan Museum. When that was discovered, it was given back to the church and when the material was translated, it turned out to be just ordinary funereal documents, which is what most scholars had believed from the beginning. This was extremely important and that I put in.

But also, I felt that I had made some speculations about the nature of Joseph Smith’s relations, and with his brothers in particular, and with his father and how that got into the Book of Mormon. That was something I had not realized before. I had not paid enough attention to his childhood, to his relations with his mother and his father, particularly his relations with his five brothers, because the Book of Mormon is a story of fratricide. It is brother killing brother all the way through. I felt this was an important idea which I had not sufficiently thought out before. I had skirted on it; that kind of thing. I felt, too, that there was more material on his mother and father that I had not used. So as I said, if I had it to do over again, the earlier portion would be more thoughtfully done. And, I think, too, I would discuss the nature of his identity problem, which I think was severe, in psychiatric terms. I could not have done it then because I did not know anything about it.

Would you care to comment a little more on that?

Well, it is just that I think he falls into a psychological pattern which had been written with very great skill by Phyllis Greenacre, a psychoanalyst, who did a wonderfully perceptive article called “The Imposter.” She defines the “imposter,” clinically, in a way that one doesn’t normally think of an imposter. She discusses the identity problem the imposter has, the degree to which he needs an audience, and the degree to which the audience, you might say, connives in the impostership; they want to believe his claims. In this case, I think the audience wanted to believe that he was truly a prophet. So the two work together.

But it is not fair to describe him as a simple imposter. This was a very special, complicated story. I don’t like to use models, but I would have used some of her material, I think, because it is extremely illuminating. I may go back and do a serious article on it someday.

Do you feel that you answered, or rather, that you really did write his history in contrast to this statement, “that no man knows my history?”

Well, I think I did much better than anybody else had. I assumed that there would be a better biography come along. It is astonishing to me that there has not been. But the book has stood up very well and perhaps one of the reasons that there hasn’t been another biography is that not enough new material has come along to make it worthwhile. The new material that has come along has tended to verify my thesis rather than to destroy it. This has been very gratifying.

In the new material that you have been able to obtain, or get access to, has . . .

It all verifies the original thesis, that his was an evolutionary process from the very beginning, that the visions probably began in some kind of child hood dream and, at any rate, were very, very different from the way he described them when he began writing his history. The fraudulent nature of the Book of Mormon is, I think unmistakable; that has not changed. The devout Mormons still believe it to be the work of God. The “Jack Mormons” are pretty certain it is not, but still respect the organization of the church and feel that it does a great deal of good, so they stay with it. I can see that there are many things about the brotherhood that are very rewarding. But I think there is no question that the Book of Mormon was fraudulently conceived. This will always be a stumbling block to people who are trying to make converts.

Was this part of your change? Did this contribute to your getting away . . .

I was convinced before I ever began writing the book that Joseph Smith was not a true prophet—to use an old Mormon phrase. Once I learned about the scientific evidence, which is overwhelming, that the American Indians are Mongoloid, I was no longer a good Mormon. That was relatively easy. It seemed to me that it was decisive.

What really prompted you to write about him at that time instead of someone else?

Well, as I say, looking back, it was a rather compulsive thing. I had to. It was partly that I wanted to answer a lot of questions for myself. There were many questions that no one had answered for me. I certainly did not get any of the answers in Utah. Having discovered the answers and being excited about them, I felt that I wanted to give other young doubting Mormons a chance to see the evidence. That, plus the fact that I had always wanted to write, made it possible—not made it possible—made it imperative that I do a serious piece of history. I found the detective work exciting, but there was always anxiety along with it because I knew it would be difficult for my family.

Were you still at the University of Utah at that time?

No, when I was writing the book, I had a job at the University of Chicago library.

As a librarian?

I was never a trained librarian but I was handing out books in the Circulation Department. I loved it; the women for whom I worked were very sweet, and I had a certain time for reading, especially when I was on the night shift. My husband was getting his doctoral degree at the university, so I had about two and one half to three years working the library where I was deeply involved in this major research.

How long, totally, did it take you to do research?

Seven years. But I had a job and was working most of that time. And then the last two years I had a baby, therefore, I never had full time to work on it.

Did you have your master’s degree at that point?

Yes, in English literature. As an historian, I am completely self-taught. At that time, at the University of Chicago, the emphasis in English literature was on the historical method so I got very good training. Later, it changed and the emphasis was on criticism rather than on history. I received excellent training in historical method.

Do you restrict yourself to biographies, exclusively?

Yes, except for an occasional thing like the speeches here and there which are on more general historical topics. But I find biography is what I love and I am more comfortable with it. I am happier with the narrative technique than I am with the topical method. Essentially, I am a storyteller.

And in this way you manipulate your heroes . . .

All historians manipulate by virtue of the selection of the material. “Manipulate” is a nasty word. The good historian tries not to manipulate deliberately but to let the material shape itself. I found, especially with the Joseph Smith book, something fascinating. I was working with non-Mormon, anti-Mormon, and Mormon material and I would get three different versions of the same episode—always two, sometimes three—and when I put them together a picture emerged that I believe had nothing to do with me, nothing to do with my selection. I was just putting all the versions together and then, as I say, it was a little like building a mosaic: you don’t create the materials, the materials are there. But somehow they fell into place, partly like a jigsaw and partly like a mosaic. It was not totally mosaic, it was a combination. It was not totally jigsaw either, but a picture emerged so often as I wrote these chapters that I thought this must be the way it happened. It was different from both the anti-Mormon and the Mormon version, but so often the mate rials fitted nicely. But what I wrote, of course, has been hotly contested by the Mormons, the devout Mormon historians, who have questioned every single line and who have gone back and read everything I wrote and found every small error and checked every footnote. But, this is the fate of anyone who writes controversial history.

The same thing is happening with the Jefferson book. I feel as if I am living my life over twice because it, too, is very controversial and the Jefferson establishment is very hostile. The book is not sold at Monticello, just as the other book was not originally sold at the church bookstore in Salt Lake City— I mean the Joseph Smith biography. But I think in time, the Jefferson establishment is more likely to come around to my point of view than the Mormon authorities in Salt Lake City.

Do you get a lot of “anti” mail from devout Mormons?

No, I have had surprisingly little over the years. I have had a great deal of mail—some of it very touching—but mostly from the young people who are on their way out of the church, are doubting, are unhappy, and are running into trouble with their families, and are writing for a little moral support. I have had many letters like that.

Are they using this as a basis for their own beliefs?

The young people who are moving out of the church find the book sometimes very traumatic and sometimes very valuable. Many of them write asking me about specific material in it. They want to go back and read what I have read. They don’t “buy” it totally; they are influenced by it, but they want to go back and redo my research and this is very healthy.

You have told me what prompted you to write about Joseph Smith. What about some of your other heroes?

The reasons that any biographer settles on any specific topic are extremely complicated. Some of the reasons are unconscious and one never knows what leads one to choose; at least, one does not know right away. I would say that, at least theoretically, or superficially, the reason I chose Thaddeus Stevens was that my husband was teaching at Yale and I had two small children and wanted to write something out of the Yale Library. I would have liked to have done a biography of Eleanor Roosevelt but that was impossible; I was too confined, so I would stay in the nineteenth century. I had looked at numerous people and rejected them all. Roger Shugg, who was working with Knopf [Alfred A. Knopf], and then later became the head of the University of Chicago Press, suggested Stevens. So I began reading about him and again I became fascinated and I felt that this was the one I wanted to write about. Those are the superficial reasons. The fact that I had tumbled headlong into the Negro problem in writing about Stevens was not an accident; I felt it was important. Any historian has to come to grips with it sooner or later, but the more I read about Stevens, the more I felt he had been abused and vilified, that this man really had elements of greatness. So, in a way, it was the reverse of the Joseph Smith.

Here, I was rebuilding a reputation that had been abused. With Joseph Smith, I felt this man whom I had been brought up to respect as a deity did not deserve that reputation. It was a total about face in terms of intention. It was good to be doing a positive thing rather than the destructive thing, because I had always felt guilty about the destructive nature of the Joseph Smith book. Although non-Mormons reading the book would never count it as being destructive, devout Mormons did, and quite properly from their point of view. The non-Mormons’ response was extremely favorable, and the historians felt this was the first really fair biography of Joseph Smith. I gave him credit for his genius as a leader as well as exposing his feet of clay.

When and why did you get into psychohistory or psychobiography, or has this been a trend all the way along?

I would say that there is none of it in the Joseph Smith book except by inadvertence. I did read a lot about paranoia when I was writing about Joseph Smith because Bernard De Voto had called Joseph Smith a paranoid, and I felt that he did not follow the classical picture of the paranoid at all, as I read the literature. So I moved back and out of the field of psychological investigation because I was not satisfied with anything that I found. Then, as I say, there have been much better things done since. The article by Greenacre on the “Imposter” [Psychoanalytic Quarterly]; much more important research is available now than there was to me then. I still say Joseph Smith was not a classical paranoid, although it may be said that, eventually, he ended up somewhat paranoid because of persecution. But the persecutions were real! If the persecutions are real you cannot say a person is paranoid; it’s only when they are unreal that you say he is paranoid. So I still would not say that he fit into that particular type. His problems were different.

With Jefferson, in handling this very controversial question of whether or not’he had a slave mistress, I looked with great interest, for example, in one of his journals written when he was living in France. He had taken a trip to Germany and to Holland. I found that in his descriptions of the landscape he used the word “mulatto” eight times: mulatto hills, somewhat whitish, mulatto land. I thought this was very extraordinary since he used the word mulatto only twice in an earlier journal. Although the word mulatto was used to describe landscape in the southern part of the United States, still, I felt it showed a special preoccupation for him since the use of it appeared eight times after the arrival of Sally Heming in Paris; whereas, the earlier journal had been written before her coming. That is the kind of thing that is the window into the unconscious. It is very treacherous, that kind of material. I have been bitterly attacked by some reviewers for that. I think it is valid data. One must be careful with it, but I do think it is an important window. There are many other kinds, slips of the tongue, for example. It is extremely useful with Nixon who makes so many of them, because he is so tense.

With Burton, there were what you might call “free associations.” Obviously, no historian can put anybody “on the couch.” When a person is dead, we must make do with what we have. But when Burton wrote about his mother, in his short autobiography, if you look at the paragraphs in which he mentions his mother and note what he said before and afterward, you will find he talks immediately about cheating, decapitation, mutilations, smashing—all the stories and metaphors are violent, negative, and hostile. After he began to write about his mother he was reminded of a mother who killed her children and was guillotined. He saw this woman executed. The immediate association to her from his own mother is very intersting. Again, that is the psychoanalytic approach. It is listening with the third ear. Again it is treacherous, but I think it is an important technique.

You keep using the terms inner versus the intimate, would you . . .

You mean, the inner life and the intimate life. Well, intimate life usually refers to the sex life, or the marriage, or relations with children and family. But the inner life is related to the intimate life. It is obviously bound up with it, but the inner life, insofar as one can get close to it, has to do with the inner conflicts that are at work in the unconscious, that are driving a person—man or woman—driving him to do whatever he is doing without being aware of these inner forces.

The presence of the unconscious has been known for generations, for centuries. When you read Shakespeare’s Macbeth and the sleepwalking scene, you will see that he understood the unconscious mind. But it was Freud who learned how to tap it scientifically and to use it in therapy. We have learned a great deal from him and the clinicians who followed him, about tapping the unconscious mind and looking at inner conflicts. This is different from the so-called intimate life.

You commented that with Smith you did not utlize this as much. There was one article written by Fisher that referred to the epilepsy in Smith’s background and “that you rather dismissed the subject.” He commented that it would be interesting to know what kind of relationship between the epilepsy and psychosis existed in your mind.

Well, I did a lot of reading on epilepsy and decided right away that he was not an epileptic. To me it is inconceivable that anyone who knows anything about epilepsy and reads Joseph Smith’s descriptions of his visions would say epilepsy was involved. An epileptic fit invariably ends in amnesia. The man or woman who has a fit remembers nothing about what happened. So to say that these visions of Joseph Smith were epileptic, is an absurdity. Epilepsy is a disease of the brain which is extremely well-known and a great deal of research has been done on it. Even fifty years ago, enough was known about epilepsy so you could not say these were epileptic fits. I think it was I. Woodbridge Riley who suggested it. He was supposed to have been a psychologist. He obviously did not know anything about epilepsy.

One of the first things I did working with Joseph Smith was to go through all the literature I could find to satisfy myself that it was not a factor. These were not fits that he had. They were dreams or visions. He mixed up dreaming and vision and dreaming and having visions. In the Book of Mormon, he has a character say, “I dreamed a dream, or, in other words, I had a vision.” I think he mixed up his own dreams and later came to call them visions as indeed his father had. His father was a visionary man, and his mother thought the dreams were so important she wrote them all down. His father’s dreams got into the Book of Mormon. That is one of the reasons why his mother’s volume is so important as a source material because you can compare her descriptions of his father’s dreams and the dreams of Lehi in the Book of Mormon, the great original “Father” of all these sons. They are strikingly similar. At least, I noted that when I wrote the book. I was sufficiently sensitive, at that point, to pick that up right away.

Did he include dreams of his brothers at anytime? Or misconstrue them?

We don’t know. If his brothers had dreams, he did not report them—or, at least, his mother did not report them. If he dreamed about his brothers, I don’t know, but certainly the Book of Mormon is a remarkable fantasy, as I said, about brothers killing brothers. But we do know, and again this is one thing I missed when I wrote it, Joseph Smith was very nearly killed when he was a teenager. Someone shot a gun and barely missed him and hit a cow instead. Nobody knew who did it. What’s more, his older brother died—this I did mention—and for some reason, the body was dug up by the father later, because rumors spread in the town that somebody else had unearthed it. So the death of the older brother, again, I think, was terribly important in his life and I underestimated the importance of it. And the shooting, the near shooting—who was shooting at Joseph Smith? Why? There were all sorts of mysteries here that I didn’t begin to try to explore.

Have you thought about exploring them now?

No, that is too far away. I am interested in other things. Certain things you put behind you and they somehow stay behind you.

It was a terrible ordeal to just go back into the literature and write the supplement. I had been collecting material for twenty years, but I did not want to do it. Friends kept pressuring me so I decided I must do it. I am very glad I did, but it was like walking back into a swamp. Mormon historiography is a swamp. You get up to your neck right away, it is so complicated. What is a fact? That is a big question. No devout Mormon and non-Mormon can agree on what is a fact. So it is terribly hard.

It depends on who does the writing.

Right. Because if you believe that Joseph Smith is a true prophet, you write in one way, and if you believe he was not, you are going to write in another way. There is simply no meeting of minds; there never will be.

What about later leaders of Mormonism?

It is easier, I think, to come to some understanding about them.

Have you anticipated writing about any others . . . ?

No. But as I told you, I thought about writing about Brigham Young many times but I always backed away from it feeling that I had gone the road with the more complicated and more interesting man. I still think Joseph Smith was one of the most fascinating men in American history.

About how long a period of time does it take you, usually, to do a book?

The Jefferson book took five years. The Burton book took five years. I won’t tell how long the Thaddeus Stevens book took except to tell you a story about my second son. When Nancy Hitch, who was the wife of the former president of the University, Charles Hitch—they happened to be good friends of ours— asked my son, “Bruce, how long did your mother spend writing on Thaddeus Stevens?” He said, “I don’t know, Nancy, but it seemed to take all my life.” (laughter) In fact, it took all his growing up [years]. I started when he was, well, just after he was born and it took a very long time. Then we had another child and we moved several times, we built two houses and I put it away for a long time. I decided I was through writing. I had three children which was enough. Three children is enormously fulfilling. It wasn’t until my daughter was three or four that I went back to the manuscript and picked it up again and decided I could not leave all those notes unused. I had done a tremendous lot of work and I was not going to stop.

Have you ever thought of writing on women?

Eleanor Roosevelt is the only one I ever wanted to write about. I spent about six months researching her and then my publisher said, “Don’t do it because Lash is doing it and he was her very good friend and had a much better opportunity to meet and know many of her friends and members of her family.” My publisher was right; it was very good advice. I am very glad I didn’t, because I could not have done what Lash did, not without infinitely more work at any rate. But then I went on to do Jefferson and that turned out to be in many ways the most rewarding of all my books. He was an authentic genius in every way, though Burton was a genius, too. Stevens and Joseph Smith had elements of greatness, but nothing like Jefferson. The richness there is beyond belief.

Do you feel that there are females “important” enough, shall we say, that they should be written about?

Oh, yes. There are many that are wonderful and there are books being written about them. There is Golda Meir and Indira Ghandi, two women who are going to be written about extensively by biographers.

In American history, I must say, the president’s wives are not a very impressive group of women. Most of them fall into the category described in the old cliche about women in Washington: “Washington is made up of talented men, and the women they married when they were very young.” I would say this is true of most presidential wives. What a dreary group they are! But a part of the problem, of course, is that there is a tradition that they must not meddle in politics. They must be dutiful wives and mothers and they must not speak out. One did speak out; Mary Lincoln did, and she was bitterly and furiously criticized for it. It was not really until Eleanor Roosevelt that we had a woman who could speak out and did speak out with distinction and talent. She was widely hated but she was a great force for good. We have not had one since. Lady Bird [Johnson] comes the closest with her beautifi cation program, but that is a nothing compared to Eleanor Roosevelt’s record.

I don’t find the suffragettes terribly exciting . . .

I have some students working with them, and they are writing some very interesting things about suffragettes, but I have not as yet settled on one that I thought I would want to spend five years with. I just find someone like Nixon far more exciting, or more challenging.

How about the modern feminists? Do you go along with some of the actions of the feminists?

People have been so kind to me. I really have managed to get so many rewards without asking for them. I was asked to join the faculty at UCLA by Eugen Weber when I was between books. I didn’t have the academic background in terms of a doctor’s degree in history. I had a great publication record—great in my eyes—and, apparently, they thought it was good enough to be asked to come into the department. So I have been treated well; I didn’t have to fight my way up the ladder. It is only now when I see the trouble my young women graduate students have that I understand what all the complaining is about. For myself, I did not have to get in there and yell. I have worked extremely hard. I worked much harder than most of the women I know have had to work, but that is because of some kind of mad, inner compulsion which has to do with God knows what. I think I have had the perfect life because I was able to raise my three children and work at home, and not have to abandon them to nursery schools or baby-sitter’s. I not only had the pleasure of raising them myself, which was wonderfully rewarding, but I was able to write at the same time. When I see my graduate students having babies and teaching and trying to write, it is an intolerable burden! I think everybody is suffering, the husbands are suffering, the children are suffering, the wives are suffering. I think it is sad. I would like to see some kind of part time teaching arrangement worked out but that seems to be impossible.

Do you go along with some of the actions of the feminists?

I don’t pay very much attention to them, really. A lot of them are shrews. I guess I am terribly old-fashioned in that respect. I agree with my husband when he quotes, I guess it’s King Lear, “Her voice was ever soft, gentle, and low, an excellent thing in a woman.” And yet, I can’t help but admire what they are doing. I believe that women have been abused and are still being abused. I go along with this, it is just that I am not a joiner or an organizer— I work alone.

You are not a feminist exactly in the way they feel?

I am a feminist, yes. I am all in favor of everything they are agitating for, I really am, because I see definite discrepancies in pay. I get paid about one third less than my husband. We are both full professors and my publication record is as good as his. It came late, but I don’t think I would ever have as much. There are very real discrepancies in pay, in the system.

People have been so kind to me. I really have managed to get so many rewards without asking for them. I was asked to join the faculty at UCLA by Eugen Weber when I was between books. I didn’t have the academic back ground in terms of a doctor’s degree in history. I had a great publication record—great in my eyes—and, apparently, they thought it was good enough to be asked to come into the department. So I have been treated well; I didn’t have to fight my way up the ladder. It is only now when I see the trouble my young women graduate students have that I understand what all the com plaining is about. For myself, I did not have to get in there and yell. I have worked extremely hard. I worked much harder than most of the women I know have had to work, but that is because of some kind of mad, inner compulsion which has to do with God knows what. I think I have had the perfect life because I was able to raise my three children and work at home, and not have to abandon them to nursery schools or baby-sitter’s. I not only had the pleasure of raising them myself, which was wonderfully rewarding, but I was able to write at the same time. When I see my graduate students having babies and teaching and trying to write, it is an intolerable burden! I think everybody is suffering, the husbands are suffering, the children are suffering, the wives are suffering. I think it is sad. I would like to see some kind of part-time teaching arrangement worked out but that seems to be impossible.

On your awards, I noticed that you had a fellowship and another award with the Commonwealth Club.

Oh, the Commonwealth Club of California. It is up in San Francisco. They give an award to books published by Californians every year. That was for the Stevens book, I think. My first was a Knopf fellowship in biography; that was before the book was finished. Knopf, in those days, was giving $2,500 to young scholars as a combination. Part of it was an outright grant and part of it was an advance against royalties and I won that before the Joseph Smith book came out. So I was able to spend some money doing traveling to research Joseph Smith which was very nice.

They didn’t consider you a Utah resident?

I was living in Washington at the time, as Bernard was in the Navy; that was during the war. The book came out in 1945.

I didn’t realize he had been military.

Yes, he was a Navy Lieutenant.

I guess you didn’t say too much about him. You started with your family.

That’s true. Well, Bernard is marvelous. He has encouraged my writing. Without him I would have never been able to do it. If I had had a husband who was hostile to my writing, as many husbands are, I think it would have been impossible. As it is, he was fascinated—I think he was by Burton, both Joseph Smith and Burton . . . also Jefferson. He was never as interested in the Stevens book, but he was a very good editor. I would give him my chapters to read when they were written as well as I could do them. He has a fine sense of style and can catch a bad sentence and improve a word here and there. He really read them with great care. He is a very, very fine editor but essentially, it was the encouragement that I got from him which was wonderful. I wouldn’t say he coached me, he’s never been a women’s libber ever, but there was this understanding of how important it was for me to keep doing this. He knew I was a lot happier when I was writing than when I was not writing. When the children were born, he recognized that. So that has been wonderful.

Is your husband from Utah?

No, he is from Chicago. I met him when I went back to do graduate work at the university. I got married the same day I got my master’s degree. We married in the morning and I went to the graduation ceremony in the after noon. I was so exhausted I slept through the whole thing! I don’t know what was said or who said it. (laughter) I was just there in my cap and gown.

What of his writing career?

He had published two books by then. His doctoral dissertation, which was Sea Power in the Machine Age, and his second book, which he wrote while we were at Dartmouth, was Guide to Naval Strategy. He has been a very productive scholar in military history and national defense.

More military than political?

It is a combination of the two. He belongs to that group of what they call the “scientific strategists”: Henry Kissinger, my husband, Robert Wolstetter, Herman Kahn and a whole group of people, who, especially after the A Bomb, began to write about the defense systems, the effect of the A-Bomb on world strategy, or national strategy. He joined Rand Corporation after he left Yale. Some of these men were gathered together at Rand and then they all went various ways. Henry Kissinger was never at Rand; he was a consultant. Bernard was one of the earliest of the scientific strategists.

Are there any articles on your list of publications that you highly recommend I read?

If you have read through my books, that’s enough. The most important things are in my books. These others are all incidental. I have very mixed feelings about one article on presidential sin. I don’t think my husband likes it too well.

Didn’t you give a paper like that in Utah?

Yes, I gave it at Utah. There is nothing psychoanalytic in this. It has to do with an old concept: lying and sin. I talk about the Ten Commandments and the Seven Deadly Sins and Quaker Sins. From one point of view, at least.

The Mormon group liked it?

Yes, they were very responsive.

Mrs. Brodie, I certainly thank you for being so gracious. I have really enjoyed the time with you.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue