Articles/Essays – Volume 55, No. 2

England’s Life of Paradox

The attacks of September 11, 2001 are a spectacular reminder that the struggle between religion and politics is alive and well in the twenty-first century. Eugene England’s life, which ended just weeks before those attacks, was very much engaged in that struggle. Although England was not a politician or even especially political in his opinions, he sought a life committed to Christian discipleship as well as intellectual freedom and integrity. These commitments, as Kristine Haglund shows in her illuminating book about England and his times, often run up against the internal politics of a religious community as well as the external relationships of a religious community with wider publics. Haglund recounts the painful personal costs of navigating an ethical life in relationship with institutions that are always pursuing their own interests. She frames this tension as a political one, and rightly so, because politics is the art of sharing a life with other human beings and with the institutions they create. Haglund captures the immense depth and breadth of this thoughtful and committed Mormon, giving us a picture of a man devoted to a Christian mission by way of dialogue.

At the base of England’s life was a commitment to dialogue, as evidenced in his act of founding this journal, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, as well as his body of published scholarship. In his works, readers can discover for themselves a writer committed to tolerance and constantly manifesting a spirit of conversation and compromise. England never seemed to write as if it was his right or anyone else’s to have the last word on a subject. His writing evinces that openness to possibility that is a key characteristic of all good conversation. An openness to possibility as well as clearly reasoned discourse make his work accessible and enjoyable. One can sense that England truly believes in and practices the “I might be wrong” persona that emerges from his writing. His style is part and parcel of the expansive version of Mormonism that allowed him to make room for “antiwar protests, antinuclear actions, feminist activism, and working for greater academic freedom at BYU” (18). While Haglund traces how many of England’s attempts at peacemaking and dialogue failed, her artful treatment of these failures acts as proof of concept that England’s attempt to live peacefully in dialogue has great merit.

It is difficult to belong to an institution of twelve million persons, roughly the number of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when England died, without experiencing some degree of difficulty wrestling with the demands of personal conscience vis-à-vis an organization that often calls for great personal sacrifice from its members. One directly senses in Haglund’s narrative the anguish of a man who is sincerely trying to do the right thing, sincerely trying to understand those with whom he disagrees in spiritual matters, including Bruce R. McConkie, a Church apostle. Haglund’s treatment of these disagreements offers a rich picture of the growing pains of Mormonism in the 1980s and 1990s and the struggle to maintain orthodoxy in a movement that emphasizes personal revelation and the dictates of individual conscience. England’s disagreement with Bruce R. McConkie “lays bear the sometimes extreme difficulty of real dialogue between authoritative doctrinal interpretation and a lay member’s earnest questions about ambiguities in the scriptural and prophetic canon” (63). Haglund highlights how productive this tension was to England and how sincerely he himself did not want it to be resolved too perfectly. After all, much is to be gained as we work through answering the call to be a Christian disciple in the midst of trials, traumas, tribulations, and tears. Without offering easy answers, without shying away from the sometimes ugly truths of institutional power, Haglund helps readers appreciate the need, in England’s words, “to live maturely as flawed persons in a flawed world” (41).

Although the case Haglund makes for treating England as a liberal is mixed, she masterfully treats the controversies in his life. It cannot be denied that England was a devoted Mormon and a sincere believer in Jesus Christ, and the best part of the book may well be Haglund’s treatment of England’s ideas on atonement. What England demanded, consistent with Latter-day Saint theology, was the freedom to bind himself to God, the conscientious ability to assent to key doctrines, to thereby maintain “both integrity and loyalty” (88). Haglund’s analysis underscores the way England practiced his religion in ordinary ways. “England’s characteristic response,” Haglund writes, “to the irresolvable tensions he articulates is action, and particularly religious practice. The argument England never quite makes explicitly is that religious practice integrates unanswerable questions into a life of meaningful action—of trying, essaying, proving contraries. Paradoxes that resist rational resolutions can nevertheless be meaningfully lived” (90). By insisting that we live with paradox, England gestures toward a measured view of the Atonement. This measured view does not place limitations on the possibilities of salvation and exaltation, but it does take seriously the need to see ourselves harnessed to the work of improving the world alongside “a weeping, compassionate God” (98). England emphasized lived religion and saw that “Mormonism’s genius lies in refusing to conflate faithfulness and orthodoxy” (101).

Readers of Eugene England: A Mormon Liberal will discover a Mormon who was as committed to dialogue and intellectual discovery as he was to faithfulness to the atonement of Jesus Christ. Those commitments necessarily involved England in his own personal tensions with authorities. Haglund is wise enough to trace those tensions and remind us we are better off with them than without them, that living in paradox is always to be preferred to living in the comfort of oversimplifications. As one of the first in an exciting new series published by the University of Illinois Press, Haglund’s book delivers on the promise of providing readers short and accessible introductions to important figures in the intellectual life of Mormonism.

There were two books about Eugene England published this past year. The other is Terryl Givens’s Stretching the Heavens: The Life of Eugene England and the Crisis of Modern Mormonism, published by the University of North Carolina Press. Both of these books present us similar views of the same man. Both books address the wrestle disciples have with their own conscience as it relates to institutional pressures and imprimaturs. Both books, and Eugene England’s life, are gifts to us as we struggle to make sense of our own agency and accountability.

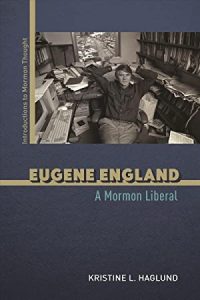

Kristine L. Haglund. Eugene England: A Mormon Liberal. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2021. 152 pp. Paper: $14.95. ISBN: 9780-252-08600-7.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and biographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue