Articles/Essays – Volume 56, No. 1

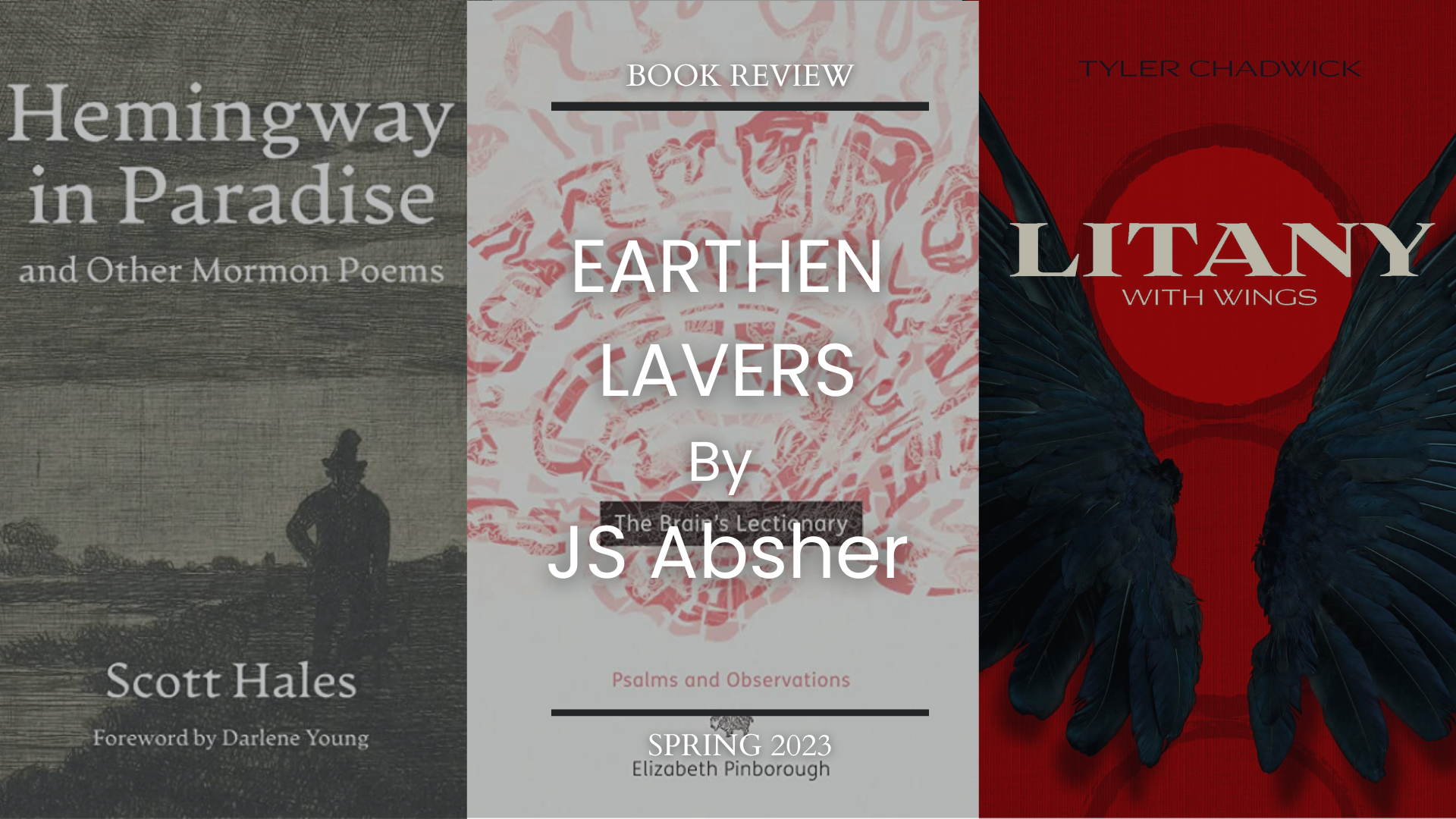

Earthen Lavers Tyler Chadwick, Litany with WingsScott Hales, Hemingway in Paradiseand Other Mormon PoemsElizabeth Pinborough, The Brain’s Lectionary:Psalms and Observations

A few years ago, William Logan wrote, “Poetry has long been a major art with a minor audience.”[1] We could more accurately call it a major art with many minor audiences grouped, like the poets, around region, identity, ideology, and artistic affiliations—a fragmentation that makes generalizations difficult. It is not easy to place in a larger context the three books I am reviewing here—Tyler Chadwick’s Litany with Wings, Scott Hales’s Hemingway in Paradise and Other Poems, and Elizabeth Pinborough’s The Brain’s Lectionary. The collection most explicitly tied to Mormon culture is Hemingway in Paradise. But suppose “Afterlives” were called “The Modern Purgatorio”? Or “Primary Activity” became “Vacation Bible School”? They would work about as well. Litany with Wings and The Brain’s Lectionary have affiliations with feminism’s goddess poetry, and both borrow heavily from the liturgical language of Catholicism, though probably in ways that suggest their non-Catholic origin. Poetry by neurodivergent poets has recently received increased attention; The Brain’s Lectionary is a brilliant example and deserves to find an audience beyond LDS circles.

Each book reviewed here is well worth the reader’s time. I enjoyed them and as a practicing poet learned much from them.

Litany with Wings

Tyler Chadwick’s Litany with Wings has five sections of thirteen poems, with an introductory and concluding poem. The publisher’s designers, D. Christian Harrison and Andrew Heiss, have designed a beautiful volume. Many of the poems are ekphrastic, based on artworks by J. Kirk Richards and others; Chadwick’s debt to these works is acknowledged in unobtrusive marginal notes, a fine design feature. The poet’s biography, as depicted in the poems, suggests he aspired to be a plastic artist until his twenty-third year (“Triptych for My Twenty-Third Year . . .”); his artist’s eye is evident is his exploration of the works that have inspired him as well as his renderings of landscape.

The language of Litany is often demanding and dense, drawing heavily on the language of the senses and of traditional Christian worship and liturgy. To see how Chadwick mixes the liturgical and the sensuous, consider the beginning lines of “Litany (in Forty Short Stanzas)”:

Ah! to tongue, snakelike,

your subtle psaltery. Totaste your staves profane

as the Ave Mariastonguing my cheek. . . . (69)

The most noticeable use of language peculiar to LDS history is the evocations of the peep stone / seer stone as object and metaphor. But the density and heightening of the language are a product of the poet’s attempt to express the unique LDS understanding that spirit and body constitute the soul. The emphasis is often on the corporeal. For instance, in depicting speech, the poems often resort to the organs of speech production also used in eating, especially the tongue, lips, and palate. Breath mingles with the flesh we consume. The poet is acutely aware of longing, appetite, and hunger in their many forms, spiritual as well as bodily. In the section devoted to recollections of his mission in New Zealand, Chadwick explores the hungers his younger self did not know how to recognize.

Perhaps the most direct statement of this theme occurs at the end of “Big Bang, with Sternutation and Seer Stones,” where the Creation and the Fall are a single event. Heavenly Father and Mother carry on a conversation that

seared the drupe-stone

seared the open palm of the adamah’s

peeping. The seed cracked wide, sighedflaming tongues of quanta through

the holy book of appetence and consciousness. (134)

“Big Bang” is the final poem in the concluding section, “Goddess in Repose: Psalter for the Eternal Mother.” Her presence is felt throughout the book in sensuous language that draws on traditional imagery of the nursing Mother of God as well as Greek descriptions of their goddesses. But Chadwick’s goddess can be more accessible and human than the Greek pantheon, as in the delightful unrhymed sonnet beginning “Goddess stirring something up, folding light.”

Hemingway in Paradise

Scott Hales’s Hemingway in Paradise and Other Mormon Poems is accessible and entertaining, effectively mixing comedy, pathos, nostalgia, and satire. The poems invite the reader to turn the page—and to turn back, too, to savor the insights and emotions. After an introductory poem, Hemingway has two sections—seventeen poems in “Afterlives,” twenty-one in “Lives.”

That Hemingway is entertaining does not mean it is not also serious. I found the poems in “Afterlives” helpful in understanding a spiritual question: in the spirit world, why would one choose to remain in a fallen state rather than accept rescue? The poems on several of the dead figures Hales writes about—Hemingway (“Hemingway in Paradise”), Clyde Barrow (“Immaterial Matter”), and Dale Carnegie (“Self Help”), for example—show how attachment to earthly habits and ideas, especially one’s self-image and worldly thriving, can block conversion. Of particular interest in this regard is the poem on Columbus, “A Man Among the Gentiles”; though in life he sometimes acted under divine inspiration, he committed grave crimes and in spirit prison cannot understand his punishment. The poem on Nathan Bedford Forrest (“Nathan”) imagines how hard repentance and forgiveness can be for those whose lives were hateful in thought and deed; the imagery faintly recalls that of the unredeemable beasts in the introductory poem, “Babylon.” Most surprising and comical to me is the state of Jonathan Edwards, the Calvinist preacher and theologian, who discovers in ping-pong the joys of exercising human agency:

Rather than look

in the sky or the dust beneath his feet, he cast

his eyes across the net, unafraid of the moment. (11)

The variety of characters and situations in “Afterlives” is impressive, but not far behind is the variety in “Lives.” This section begins with a poem on W. W. Phelps’s observations on the comet Donati (“When W. W. Phelps Observed Donati”), then proceeds to the poet’s impromptu and hilariously rendered moonwalk while he was attending a Primary activity night (“Primary Activity, 1984”):

I shimmy once and spin

on my heel. And though I know

I shouldn’t, I spring to my tippy-toes,knees bending at the tight right

angles, and grab my tiny crotch

with the green-mittened hand. (37)

The next poem imaginatively recasts the relationship of King Noah and Abinadi as beginning with boyhood friendship and ending in their fiery deaths (“As King Noah Burned”).

Reading Hemingway in Paradise brought to mind a saying of Nietzsche: “Everything that is good is light. All that is divine runs on delicate feet.”[2] These poems are light on their feet and divinely full of understanding, wit, and love.

The Brain’s Lectionary

Elizabeth Pinborough’s The Brain’s Lectionary: Psalms and Observations is another beautifully designed book from By Common Consent Press. Drawn from the poet’s experience with traumatic brain injury, it is addressed especially to “anyone in extremity,” including “those living with the long-term consequences of brain injury, chronic health concerns, or any trauma that shatters the body and the relationship with the self” (“Introduction,” xvii). But its appeal is broader. The experience of losing so much—the grasp on language, one’s relationships to God and to ordinary life, and so much else constitutive of the self—is movingly and imaginatively told. Unlike many who undergo such experiences, Pinborough has returned to tell us all.

Lectionary is a hybrid volume with shape poems, prose poems, a short verse play, psalms, typographic experiments, and linocuts by the author and others. Each form has a purpose. For example, “shape poems serve as strange devotions for inexpressibly hard times” (xv). The typographical experiments mimic “the way eighty billion individual neurons in the brain communicate across synapses to become functional networks.”

A lectionary is a collection of scripture readings appointed for a given day, often in a two- or three-year cycle. The Brain’s Lectionary has fifty-two poems, presumably one for each week of the year, weeks described in “The Psalmist Inquires, Under what moon?” as “the / rimrock round of lunar / canyons (fifty-two / cycles complete)” (111). As in Litany with Wings, many of the poems are ekphrastic, but Lectionary includes the images for our consideration—twenty graphic works in all, some repeated and some spread over two pages.

In expressing the experience of brain injury and recovery, Lectionary encompasses a vast range of existence, from undersea life to galaxies, with the brain’s cells and electrochemistry at the center. The slipperiness of language and imbedded metaphor as well as visual resemblances between unlike life-forms enables the poet to yoke these heterogeneous levels of existence. “Big Bang Neurogenesis” describes how “astrocytes died”—astrocytes are star-shaped brain cells—and how their “remains . . . emerged as new matter—a kind I cannot see but know // to name since stars spin alike at center and circumference in galaxies” (42). “Purkinje ekphrasis” is a meditation on an image of Purkinje cells:

Purkinje looks like

a little heart,

leafingfrom aorta into

seaweed

fronds. (73)

Some of the poems that resonate most deeply depict the injured self as lost at sea—“I drifted in quarter consciousness like a raft on the sea” (“Threshing with God,” 128)—or deep in the ocean; in “Pseudoliparis swirei,” the traumatized mind is a ghostlike snailfish deep in the Mariana Trench. Perhaps my favorite is “Jared’s Answers”; in response to the Lord’s question, “What will ye that I should do that ye may have light?” (Ether 2:23), Jared requests the light and signals found in sea life:

Give me blue paths, bioluminescence

across the waters. Give me constellations

dotting firefly squid. . . .

Give me . . .

dinoflagellates flashing on,

off. (63)

In reading and pondering these books, I have been impressed by their worlds of “earthy spheres, invisible lives, miraculous / micro-architectures” (“Klaus the Diatomist . . .,” The Brain’s Lectionary, 83) that will move, challenge, and inspire the careful reader. The publishers, By Common Consent and Mormon Lit Lab, deserve praise and support for nurturing these writers and publishing their works in such well-designed, affordable editions.

Tyler Chadwick. Litany with Wings. By Common Consent Press, 2022. 158 pp. Paper: $9.95. ISBN: 978-1948218566.

Scott Hales. Hemingway in Paradise and Other Mormon Poems. Mormon Lit Lab, 2022. 93 pp. Paper: $9.99. ISBN: 979-8797250760.

Elizabeth Pinborough. The Brain’s Lectionary: Psalms and Observations. By Common Consent Press, 2022. 180 pp. Paper: $11.95. ISBN: 978-1948218474.

[1] William Logan, “Poetry: Who Needs It?,” New York Times, June 14, 2014.

[2] Original German: “Das Gute ist leicht. Alles Göttliche läuft auf zarten Füßen.” This aphorism appears on the first page of Der Fall Wagner, translated as The Case of Wagner in English. See Friedrich Nietzsche, The Case of Wagner / Twilight of the Idols / The Antichrist / Ecce Homo / Dionysus Dithyrambs / Nietzsche Contra Wagner, edited by Alan D. Schrift (Redwood City, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2021).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue