Articles/Essays – Volume 46, No. 4

Early Mormon Priesthood Revelation: Text, Impact, and Evolution

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

Joseph Smith’s revelation texts carved out a complex system of ranks, offices, jurisdictions, and judicial bodies that implicitly rejected the feminization of Protestantism, while forwarding a selective blend of biblical terminology, Book of Mormon-defined praxis, and antebellum legalisms in organizing an exclusively male “priesthood” structure.

The purpose of this paper is to examine some early Mormon revelation texts on priesthood, to begin to understand those texts in the context of their time and place, and to briefly observe how those texts influenced later Mormonism.The textual foundations of Mormon liturgy are not just the seed of praxis, they also created doctrine, even if some of it was temporary. Joseph Smith’s narrative of angelic visits and handbook-like revelations systematized and organized a hierarchy that gradually became self-sustaining even through the shock wave of his own death. His apostolic successors took these durable texts and fading memories of early contexts to form an ever-evolving picture of governmental structure that paralleled reinterpretations of the purposes of that structure.

The essential texts and innovations that outlined and generated this evolution began with the 1830 Articles and Covenants of the Church of Christ. This initial text was followed by the ordination of a Church bishop in 1831. The nature of this office and those established in 1830 caused difficulties in understanding their relative positioning in the hierarchy. A new office, high priest, was introduced in June 1831, and following it in November 1831, revelations provided the beginnings of a skeletal structure that limited the bishop in several ways and formally placed Joseph Smith in a supervisory role. The revelation of November 11, 1831, went through some revision, and I present a possible proto-text for that pivotal revelation to help in understanding how revelations delivered early in 1832 further enriched this structure. The fall of 1832 saw revelation that opened a richer, if intermediate, hierarchical structure. At the beginning of 1835, more offices were added to the Church: the twelve apostles and the seventy. A revelation incorporating these offices in the hierarchy appeared in April 1835. These founding texts are studied in some detail below, together with consideration of how this hierarchy was reinterpreted in the decades after Joseph Smith’s death.

Summary of the Article

Specifically, I will treat these texts and developments as they center around what is now Doctrine and Covenants section 107. Sections of the paper and their contents are:

1. Defining Revelations. Here I discuss, among other issues, parts of the Articles and Covenants of the Church of Christ, an early document now found essentially in section 20 of the Doctrine and Covenants.

2. High Priesthood—Catalyst for Change. This section opens the discussion of some of the leadership dynamics between Church officers mentioned above.

3. A Possible Proto-Text for the John Whitmer Portion of the Revelation of November 11, 1831. I deliver a close reading of the text of a November 11, 1831, revelation that later became a part of Doctrine and Covenants section 107 (there were at least two, perhaps three revelations delivered on November 11). In this case, I use the Revelation Book 1text redactions to reconstruct a possible proto-text of the first portion of the revelation. This revelation introduced a new hierarch, the president of the high priesthood.

4. The Beginning of Church Discipline Structures—A Possible Proto Text for the Oliver Cowdery Portion of the Revelation of November 11, 1831. This section of the paper notes and contextualizes the segment of revelation begun in the previous section. Church discipline was outlined in the revelation, responding to a further need for behavioral boundaries in the new Church.

5. Guarding against Prelate Tyranny. Church discipline provisions outlined by the November 11 revelation extended to procedures for dealing with a president of the high priesthood. These procedures were important at the time and can be seen in part as responding to Protestant fears of prelate tyranny.

6. What Did “Priesthood” Mean in 1831 Mormonism? This section briefly discusses the beginning of an ongoing theme in the paper: how the word “priesthood” evolved from reference to office to category to liturgy. At this point, the reader may wish to consult Appendix 2 of the paper, which lays out by parallel genetic text the relationship between the proto-text of the November 11 revelation and a later manuscript edition found in Revelation Book 2.

7. Interregnum—The Beginnings of Internal Structure—“Appendages.” The current section 107 of the Doctrine and Covenants is a compilation of revelations, beginning with the November 11, 1831, revelation itself. As Appendix 2 and the proto-texts suggest, the November revelation may have been at least two revelation episodes. Between the major manuscripts of the November revelation (s) there exist several important conceptual expansions. These were initiated or at least codified in a September 1832 pair of revelations, now represented as section 84 of the Doctrine and Covenants. Between the November 1831 and the September 1832 revelations, several steps were taken to implement the establishment of the Presidency of the High Priesthood, an important hierarchal step later meshed with practical developments in an April 1835 revelation. The following year further revelation texts expanded the presidency’s purpose.

8. The April 1835 Revelation. A revelation delivered at the request of the newly ordained apostles reads as a lecture-summary of the way Smith had been thinking about theological foundations of official taxonomy. It became the initial segment of what is now section 107. A close reading of this revelation appears here and captures much of the ongoing use of name/terms such as Melchizedek and Aaronic and relative status of new priesthood groups, including patrilineal descent narratives for various officers and particular bishops who were now written into a new grouping, the Aaronic order.

9. Holy Protologies—Holy Descendants. This part of the paper responds to the mythos announced in the 1832 and 1835 revelations in the context of holy families, a meme that links to both ear lier and later revelations, as well as to the adoption theology that expanded in the post-Joseph Smith era.

10. Eras in Collision—Editing the November 11, 1831, Revelation. With the decision to attempt another issuance of Joseph Smith’s revelations (realized in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants) came the publication of the November 11 revelation, not as an independent text, but as a subtext following the April 1835 revelation. However, the priesthood theories presented were based in different eras of thought and usage in Mormonism. This part of the paper shows how the November revelation was redacted in the attempt to link the two eras.

11. Kirtland and Missouri Dissent and Canonical Modifications. Disciplinary procedures for a Church president were encoded in the November 1831 revelation. With dissent at Kirtland, Ohio, those procedures were now in play. Three revelations in 1838 responded to this situation, revamping the original procedures in ways that made it much more difficult for a single arena to decide the fate of the highest Church leaders. The revelations were “canonized” but never became part of Church-published revelation collections.

12. The Deprecation of the High Priesthood and Its Legacy—A Case Study. The 1835 publication of the November revelation gave textual authority to the superiority of the High Priesthood among fellow Church offices by making the Presidency of the High Priesthood the textual equivalent of the newly evolved title of First Presidency (see section 7 of the paper). With the death of Joseph Smith, there were several ways for Mormonism to find its new leader. The ascendancy of the apostles carried with it a necessity to read the revelation texts in a different way. This part of the paper discusses some of these developmental issues and offers part one of a case study in Joseph F. Smith’s response to the tensions inherent in Church discourse between 1831 and 1918.

13. Ordination Practice and the Revelations. The second part of Joseph F. Smith’s impact on ecclesial priesthood is studied here. Smith’s views in the 1870s gradually changed as he began to read D&C 107 in a new way, finding in the April 1835 revelation a new liturgical imperative. The effect of Smith’s ideas eventually bore fruit in the 1960s as Church liturgy absorbed those ideas on ordination.

14. The Genesis of Mormon Clerical Structure. In this part of the paper, I return to the evolution of ecclesial priesthood with an office overview and review of referential change and the meaning and use of “quorums” in rereading the early revelations for the needs, practicalities, and policies of the Church in Utah.

15. Discipline and a President of the Church. One of the key points of the November 11 revelation was a provision for recalling the President of the High Priesthood. That provision changed in both text and possible implementation through the next century. I discuss the realities of such discipline in terms of the revelation.

16. Epilogue: Elijah, Sealing, and a Summation of Successional Realities. The self-vision of the Mormon leadership is founded in more than the 1830s revelations. Much of the 1840s involved an empirical realization of the theological promise of the 1830s. Several developments set the course for succession after Joseph Smith. These were deeply connected to temple theology and polygamy. The interplay of the revelations and Nauvoo realizations is important in understanding the foundations of current Mormon narratives of why and how present praxis exists.

Appendices. There are two appendices. Appendix 1 is a stemma for D&C 107, illustrating the contributing threads of the section. Appendix 2 compares texts of the November 11 revelation and its later Revelation Book 2 incarnation. The textual changes are intermediate to those found in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants (see section 10 of the paper).

1. Defining Revelations

Section 107 of the Doctrine and Covenantshas historically played a major role in both defining and proof-texting government in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as well as some other manifestations of Mormonism following Joseph Smith’s death. It is a remarkable document for many reasons. No discussion of early Mormonism can be complete without an understanding of this and Smith’s other revelations that explicate Mormon priesthood; this requires a careful deconstruction of those texts, including their historical context, genesis, and eventual interpretation.

The introduction of a formal “priesthood” and the development of a corresponding ecclesial structure in early Mormonism began with early revelations that took officers called teachers, priests, and elders (the word “apostle” is used, but the new Church’s Articles and Covenants defined this as an elder) from the pages of the Book of Mormon.At some early date, perhaps with the text of D&C 20 following Church organization, another office, deacon, was added. There was no division of authority (no “Aaronic Priesthood” or “Melchizedek Priesthood” in later terms), merely named offices with different permitted practice for each one (except in the case of deacon—allowed to do the duties of the teacher, as required). A teacher would head a congregation where no other officers were present. A priest functioned as meeting chair in the absence of elders. In practice, congregations or impromptu meetings often selected the presiding officer or moderator from among the eligible office holders.

Duties of the various offices were close to those found in branches of Protestantism, such as home visiting of members, performing baptisms, administering the Lord’s Supper, etc. The basic organizational structure consisted of Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery as “first and second elder” together with the mentioned pecking order among the early offices.

2. High Priesthood—Catalyst for Change

In June 1831, the office of high priest was introduced during a multi-day conference.The office was added to the list of those already given, and was regarded as a higher office with du ties that had not surfaced previously, particularly in the area of salvation assurance. Previous to this, the office of bishop had been established with certain open-ended duties whose relationship to other Church officers was unclear. Edward Partridge was ordained a bishop February 4, 1831. Partridge was ordained a high priest in June, but the relationship of his bishopric to that circumstance was not clear at the time. Local groups of Church members selected their leaders from the group, or those leaders were appointed by missionaries preaching in the area.These groups are often referred to as “churches” in the revelations. But priesthood offices were still without a formal internal structure: no architecture like “Aaronic Priesthood,” no “quorums,” or quorum presidents, etc.

Organization was added in 1831 with a revelation given on November 11, in Hiram, Ohio. The “autograph” of the revelation may be lost, but a very early copy is found in Revelation Book 1. This copy is in the handwriting of John Whitmer and Oliver Cowdery. It was intended for the Book of Commandments; complete typesetting failed by virtue of the destruction of the printing office in Independence, Missouri, in 1833. The revelation was a foundation for D&C 107. Its importance as textual precursor to much of Mormon praxis and both formal and informal administrative thought cannot be overemphasized. Given that importance, I have constructed a version of this text that may be an early form, based on Revelation Book 1.

3. A Possible Proto-Text for the John Whitmer Portion of the Revelation of November 11, 1831

The Revelation Book 1 text of the November 11 revelation appears in the hands of John Whitmer and Oliver Cowdery. The portion immediately below corresponds essentially to the Whitmer text.

A Revelation given at Hiram Portage Co Nov 11th 1831

To the Church of Christ in the Land of Zion in addition to the Church Laws respecting Church business verily I say unto you, saith the Lord of hosts there must needs be presiding Elders to preside over them who are of the office of an Elder: & also Priests over them who are of the office of a Priest; & also Teachers over them who are of the office of a Teacher, & from Teacher to Priest, And also the deacons; wherefore from Deacon to Teacher, & from Teacher to Priest, & from Priest to Elder; severally as they are appointed, according to the Church Articles & Covenants: then cometh the high Priest hood, which is the greatest of all: wherefore it must needs be that one be appointed of the high Priest hood to preside over the Priest hood: & and he shall be called President of the

hoodhigh Priest hood of the Church; or in otherhighwords the Presiding high Priesthoodover the high Priesthood of the Church; from the same cometh the administering of ordinances & blessings upon the Church, by the Laying on of the hands: wherefore the office of a Bishop is not equal unto it; for the office of a Bishop is in administer ing allthingstemporal things: nevertheless a Bishop must be chosen from the high Priesthood, that he may be set apart unto the ministering of temporal things, having a knowledge of them by the Spirit of truth; & also to be a Judge in Israel to do the business of the Church, to sit down in Judgement upon transgressors upon testimony it shall be laid before them according to the Laws, by the assistance of his councillors whom he hath chosen or will choose among the Elders of the Church.

This portion of the revelation resolves (in part) several of the issues outlined above. It creates a new hierarch, the president of the high priesthood, who would preside over the other priesthood offices of the Church.It acknowledges that the Articles and Covenants (again, essentially D&C 20) did not cover the necessary ground. The high priesthood is designated “the greatest of all.” In the ordering of offices in D&C 20, this places the high priest above the other offices—deacon, teacher, priest, elder. That ordering is based primarily on who takes charge in groups. Joseph Smith kept that ordering intact as further priesthood offices were introduced. Even so, the office of high priest still constituted the office that “presides” but it was a status that became less meaningful with the development of bureaucratic structure.

The president of the high priesthood became what the Latter-day Saints later called the “president of the Church.” The revelation also partially mapped the office of bishop, an important feature, since Edward Partridge had been a bishop for nearly a year.

The revelation makes clear that the bishop should be a high priest though he may have counselors selected from the elders at this point—it was not until 1877 that bishops’ counselors were required in practice to be high priests. By 1877, Church leaders saw the judicial aspects of the bishopric as requiring the high priest hood. In the revelation, the bishop ranks below the president of the high priests, and this resolved an important difficulty in Church administration (i.e., where did the bishop’s dictates stand in relation to Joseph Smith, for example). The revelation intro duces the idea of “keys” (in the sense it came to be used decades later) without actually using the word, by designating the president of the high priesthood as the office which controls administration of ordinances, and “blessings on the Church by the laying on of hands” (perhaps a nascent reference to the future office of “patriarch” as well as further defining where the bishop stood in relation to the president).

Two other matters are suggested by the preamble of the revelation. This revelation is an addition to the law of the Church. And it applies particularly to the Church in Zion (Missouri). At least part of the reason for the latter provision was the fact that Bishop Partridge became a resident of Independence, Missouri, months prior to this revelation.Finally, the role of the bishop in Church discipline is briefly outlined. In the second part of the revelation, there is further information on Church discipline and the role of the president of the high priesthood in that.

4. The Beginning of Church Discipline Structures— A Possible Proto-Text for the Oliver Cowdery Portion of the Revelation of November 11, 1831

The November 11, 1831, revelation divides naturally into two segments, properly corresponding to what may have been two separate revelations. The first revelation begins with the portion quoted in the previous section in the hand of John Whitmer and concludes in the Oliver Cowdery portion given below with the word “Amen.” This “Amen” terminates judicial discussion of the revelation and begins a discussion of internal official structure. Therefore, if we include the base text of D&C 69 at least three revelations were dictated by Joseph Smith on November 11. When the terms “first” and “second” revelations of November 11 are used below, they do not refer to the base text of D&C 69, but to the combination of the portions of the proto-text given in this section and the previous section of the paper, as separated by the first “Amen” below.

thus shall he [the bishop] be a judge even a common judge among the inhabitants of Zion until the borders are enlarged, & it becomes necessary to have other Bishops or judges. & inasmuch as there are other Bishops appointed, they shall act in the same office. & again, verily I say unto you, the most important business of the church, & the most difficult cases of the church, inasmuch as there is not

suffi cientsatisfaction upon the decsision of the judge, it shall be shall be handed over, & carried up unto the court of the church before the president of the high Priesthood & the president of the Court of the high priesthood shall have power to call other high priests, even twelve to assist as counsellors, & thus the president of the high priesthood, & his councellors, shall have power to decide upon testi mony, according to the laws of the church; & after this desision it shall be had in remembrance no more before the Lord; for this is the highest court of the church of God & a final desision upon controverses, all persons belonging to the church are not exempt from this court of the church & inasmuch as the president of the high priesthood shall transgress, he shall be had in remembrance be fore the common court of the church, who shall be assisted by twelve councellors of the high Priesthood, & their desicision upon his head shall be an end of controversy concerning him. thus none shall be exempt from the justice of the Laws of God, that all things may be done in order, & in solemnity before me, to truth & righteousness. Amen. A few more words in addition to the Laws of the church. And again, verily I say unto you, the duty of the president over the office of a Deacon, is to preside over twelve Deacons, to set in council with them, & to teach them their duty, edifying one another as it is given according to the covenants.And also the duty of the president over the office of the Teachers, is to preside over twenty four of the Teachers, & to set in council with them, & to teach them the duties of their office as given in the covenants. Also the duty of the presi dent over the priesthood is to preside over forty eight priests, & to set in council with them, & to teach them the duties of their office, as given in the covenants.And again the duty of the president over the office of the Elders, is to preside over ninety six Elders, & to set in council with them, & to teach them according to the covenants. And again the duty of the president of the office of the High Priest hood, is to preside over the whole church, & to be like unto Moses. behold here is wisdom: yea, to be a Seer, a revelator, a translator, & prophet, having all the gifts of God, which he bestoweth upon the head of the chuch: Wherefore now let every man learn hisdulyduty, & to act in the office in which he is appointed., in all diligence. he that is slothful shall not be counted worthy to stand. & he that learneth not his duty & sheweth himself not approved, shall not be counted worth to stand; even so: Amen.

The establishment of Church courts begins here. There is a court of common pleas (headed by the common judge), a mimic in terminology and duty of the common law courts of antebellum America, particularly in Ohio and New York. The word “common” takes its meaning from a standard name for lower state courts of the period (and their British common law counterparts), which heard civil and minor criminal cases.

The bishop is assigned the role of judge in the lower court. There may be a “jury” attached to a case in certain instances. The courts of common pleas typically handled civil disputes, and the bishop’s court would do the same. Cases where a Church member had a complaint against another member might be handled by this common court. The name implies that lesser infractions were the province of the bishop and that any Church member had access to this court for redress of complaint.

Following the setup of the lower court system, the revelation continues with the establishment of a superior court structure. The superior court is attached to the president of the high priesthood and functions as both an appeals court (indeed, the court of final appeal at this point) as well as one of original jurisdiction in complex or serious cases. This court may not function without what is essentially an ad hoc twelve-man jury, made up of high priests, who have no permanent status beyond a given court session, at least on paper. Again, this superior (supreme) court handles difficult cases of Church discipline, disputes between Church members, or cases on appeal.

5. Guarding against the Abuse of Authority

As a final provision, the president of the high priesthood may be tried, obviously not by the superior court system, but in the companion lower court, the “common council.” This is an augmented common court (i.e., the bishop) with a twelve-man jury (again they are to be high priests). The bishop together with his jury would pass judgment on the president of the high priesthood.One glaring lack in the provision exists. If the president of the high priesthood is disciplined, perhaps removed or even cut off (excommunicated), then how is he to be replaced? It was some time before this gap in the system was addressed. Late in the Kirtland period (1837), the president of the high priesthood would go before the common court. However, by then there was some provision for succession.As the revelation says, “none shall be exempt from the justice of the Laws of God,” a phrase which defines the jurisdiction of these courts as applying to Church matters, or at least involving Church members.

The establishment of the president of the high priesthood changed some provisions in revelations given earlier in the month of November 1831. For example, a revelation given November 1 outlined provisions for selecting new bishops, who were now to be high priests. They were to be selected by a “conference of high priests.” The text of that revelation would evolve considerably by the time of its publication in the Doctrine and Covenants (1835). Those changes were deployed largely in response to the establishment of the president of the high priesthood and other provisions of the November 11 revelation.

The last portion of the revelation sets out group organization for existing priesthood offices: deacon, teacher, priest, elder, and high priest. There is no provision for presidencies in the revelation. Each office gets a president. The sizes of these groups (“quorum” would not be used for some time) seem small (twelve for the deacons), but this was not a real issue at the time; most men, when ordained at all, were ordained elders up to the June 1831 conference. Church conferences, where records exist in this period, documented small numbers. The October 25, 1831, conference at Orange, Ohio, noted twelve high priests, seventeen elders, four priests, three teachers, and four deacons. The idea of having multiple quorums of deacons, teachers, priests, and elders is not addressed but is perhaps suggested by the numerical restrictions. In any case, quorum size was not carefully observed. The Kirtland elders quorum grew to 300 members at one point. Quorum membership and leadership were generally a matter of election prior to 1841.The high priests have no numerical restriction, but they form a group as suggested in the establishment of the president. Joseph Smith did become president of the high priesthood, but not until the following year. The establishment of a presidency (counselors) had to wait for several months.

6. What Did “Priesthood” Mean in 1831 Mormonism?

The revelation shows something of the way the early Church used titles. The phrase “Also the duty of the president over the priesthood is to preside over forty-eight priests” signals that the word “priesthood” was used in exactly the same way that “high priesthood” was: priesthood referred to the office of priest. There was no concept of Aaronic and Melchizedek divisions at this point.When Smith quoted John the Baptist saying, “Upon you my fellow servants, in the name of Messiah I confer the Priesthood of Aaron” this meant that Smith and Cowdery were thereby made “priests.”“Priesthood” was gradually understood differently after 1835 and the original usage was essentially lost by the twentieth century. But in revelations prior to 1835, phrases like “lesser priesthood” (for example D&C 84:30) referred to the office of priest.Reading the revelations without that in mind has generated acontextual readings over time.

The November 11 revelation outlines regulation of the priests group. It was to have a president from among its number. This was modified in 1835: the presidency of the priests group (later, “quo rum”) would eventually fall to the office of bishop, without the benefit of counselors (see below).

7. Interregnum—The Beginnings of Internal Structure—“Appendages”

D&C 107 is a compilation of revelations. There are two major parts in the compilation, one from November 1831 that I have briefly considered above, and another from April 1835. In D&C 107 these are arranged in reverse chronological order. It will be apparent later that the 1835 segment has a rather different character than the 1831 segment and may itself be seen as a historical compilation. As these two revelations were combined in the 1835 D&C, still other revelations and regulations were interleaved in these texts to form what we now know as D&C 107. The period between 1831 and 1835 exhibited rapid developments in Mormon leadership structure.

Between the various texts of the November 11, 1831, revelation and the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants text (section 3 of that first edition, 107 of the 1981 edition) there were several developments. Among these were the two important revelations of September 22, 23, 1832,combined as LDS D&C 84. In this text we see the beginnings of a taxonomy of Mormon priesthood, more nuanced than previous classifications, but not yet mature. The September 1832 revelations review the two “priesthoods” in the Church at this point.

It is useful to recall that:

1. the lesser priesthood (or just “priesthood” in 1831) = the of fice of priest,and

2. the high priesthood (or occasionally, just “priesthood” in the following text) = the office of high priest.

Within modern Mormonism, it is very common in Church literature and discussion referencing D&C 84 passages to assume that lesser priesthood references the concept of the Aaronic order and high priesthood is the Melchizedek order, but this is incorrect.In 1832 the more refined and paradigm-shifting notions of Melchizedek Priesthood and Aaronic Priesthood had not surfaced yet in any well-defined way. As one can see, this both rationalizes but also changes the currently assigned meaning of passages like this one (D&C 84:31–42):

31 Therefore, as I said concerning the sons of Moses—for the sons of Moses and also the sons of Aaron shall offer an acceptable offering and sacrifice in the house of the Lord, which house shall be built unto the Lord in this generation, upon the consecrated spot as I have appointed—

32 And the sons of Moses and of Aaron shall be filled with the glory of the Lord, upon Mount Zion in the Lord’s house, whose sons are ye; and also many whom I have called and sent forth to build up my church.

33 For whoso is faithful unto the obtaining these two priesthoodsof which I have spoken, and the magnifying their calling, are sanctified by the Spirit unto the renewing of their bodies.

34 They become the sons of Moses and of Aaron and the seed of Abraham, and the church and kingdom, and the elect of God.

35 And also all they who receive this priesthood receive me, saith the Lord;

36 For he that receiveth my servants receiveth me;

37 And he that receiveth me receiveth my Father;

38 And he that receiveth my Father receiveth my Father’s king dom; therefore all that my Father hath shall be given unto him.

39 And this is according to the oath and covenant which be longeth to the priesthood.

40 Therefore, all those who receive the priesthood, receive this oath and covenant of my Father, which he cannot break, neither can it be moved.

41 But whoso breaketh this covenant after he hath received it, and altogether turneth therefrom, shall not have forgiveness of sins in this world nor in the world to come.

42 And wo unto all those who come not unto this priesthood which ye have received, which I now confirm upon you who are present this day, by mine own voice out of the heavens; and even I have given the heavenly hosts and mine angels charge concerning you. [Emphasis added.]

“Sons of Aaron” is synonymous with priests, “sons of Moses” is a similar title for those ordained high priests.Thus the “oath and covenant,” as this passage is commonly called, really applies to those of the high priesthood. However, consider the more detailed authority architecture introduced by the revelation:

29 And again, the offices of elder and bishop are necessary appendages belonging unto the high priesthood.

30 And again, the offices of teacher and deacon are necessary appendages belonging to the lesser priesthood, which priesthood was confirmed upon Aaron and his sons.

Here, two subgroups of priesthood offices are now defined, one headed by the office of high priest, the other by the office of priest. Other offices are defined as “appendages” to these two— that is, something added to the principal idea or object, but not necessary. We see here the beginnings of the more mature taxonomy to be laid out in 1835. But that reclassification was consider ably more radical in a number of ways.

Making the office of elder an appendage to the high priesthood brings the elders, riding the coattails of the high priests, into the covenant cycle mentioned above. The April 1835 revelation (and major contribution to D&C 107) alters this relationship still further.The bishop, while still an appendage to the high priesthood, is different from the elder. No elder is required to be a high priest first, before acting as an elder (whatever that might mean), while the office of bishop began and remained an ordained office, later seen in the September 1832 revelations, as growing out of the high priesthood. But a bishop, both in theory and in practice, must also be a high priest. This duality of ordination eventually made its way into other offices beyond the lesser priests (where the bishop was theologically located in 1835), for example, patriarch, seventy, and, according to Joseph F. Smith, apostle.

The revelation of November 11, 1831, was accepted in Zion (Missouri) as an addition to the law of the Church on July 3, 1832, but remained unpublished to the body of the Church.The office of president of the high priesthood stood vacant until a January 25, 1832, conference at Amherst, Ohio, when Joseph Smith was elected to fill the office. Sidney Rigdon “ordained” Smith at the time (Joseph Smith was ordained a high priest in June 1831). Between that time and March 8, 1832, Smith became acquainted with the idea of having counselors, forming a “presidency” of the high priesthood. A revelation received on March 5, 1832, reads in part,

unto the office of the presidency of the high Priesthood I have given authority to preside with the assistence of his councellers over all the concerns of the church wherefore stand ye fast claim your priesthood in authority yet in meekness and I am able to make you abound and be fruitfull and you shall never fall for unto you I have given the keys of the kingdom and if you transgress not they shall never be taken from you. Wherefore feed my sheep even so Amen.

On March 8, 1832, Jesse Gause and Sidney Rigdon became Smith’s counselors.Gause was the subject of a revelation at the time, which now appears as D&C 81, outlining his duties. At a subsequent conference in Missouri in April, the presidency was also sustained. The establishment of the Presidency of the High Priesthood was interrupted during the summer of 1832 when Gause left on a mission, never to return, and Rigdon had a mental break down, in part over his continuing issues with Edward Partridge, and was removed from office for a time.Rigdon was reinstated that fall but no successor to Gause was chosen until 1833.

In January 1833 Joseph Smith received the following revelation:

Behold I say unto you my Servent Frederick, Listen to the word of Je sus Christ your Lord and your Redeemer thou hast desired of me to know which would be the most worth unto you. behold blessed art tho[u] for this thing. Now I say unto you, my Servent Joseph is called to do a great work and hath need that he may do the work of translation for the Salvation of Souls. Verily verily I say unto you thou art called to be a Councillor & scribe unto my Servent Joseph Let thy farm be consecrated for bringing forth of the revelations and tho[u] shalt be blessed and lifted up at the last day even so Amen.

Williams was not formally set apart (ordained—the terminology was fluid) until March 18.

On March 8, 1833, a revelation (D&C 90) was received which directed that Rigdon and Frederick Granger Williams be Joseph’s counselors. Moreover, the revelation directed that they hold the “keys” jointly with Joseph. Their role in the presidency was outlined:

6 And again, verily I say unto thy brethren, Sidney Rigdon and Frederick G. Williams, their sins are forgiven them also, and they are accounted as equal with thee in holding the keys of this last kingdom;

7 As also through your administration the keys of the school of the prophets, which I have commanded to be organized;

8 That thereby they may be perfected in their ministry for the salvation of Zion, and of the nations of Israel, and of the Gentiles, as many as will believe;

9 That through your administration they may receive the word, and through their administration the word may go forth unto the ends of the earth, unto the Gentiles first, and then, behold, and lo, they shall turn unto the Jews.

Rigdon then requested that Joseph do as the revelation stated and on March 18 both he and Williams were “ordained” to stand with Joseph, holding the keys of the priesthood. The meaning of this morphed over time, and that change made it possible for the apostles to send Rigdon packing in the August 1844 succession disputes. Smith used “keys” in a number of ways as temple cosmology came to the forefront of Nauvoo teaching. The Book of Abraham publication in 1842 supported these ex pansions as did the incorporation of Masonic world-views into Nauvoo rhetoric. Keys were not just associated with hierarchical position. They were also sacred words and signs and other sacral knowledge.

Further evolution in the Presidency of the High Priesthood took place the following year (1834) with the coming of a permanent (standing) council of high priests, the “high council.” Members of the presidency were designated as supervisors of the body who in some sense acted as both attorneys and jurors. Organizational minutes suggest these officers were to give lifetime service, absent removal from the jurisdiction of the council, death, or transgression. In the founding document of the institution, the presidency receives some further refinement in regard to the counselors or assistants as they were sometimes called in Church minutes.They are able to function alone, without the president, perhaps acknowledging the 1833 revelations. Indeed, all three were designated presidents, a tradition that passed to stake presidencies and derived from their essential equality of authority in the D&C 102 minutes.

In the meantime, there was a terminological shift, as well as a succession provision. Early New York convert David Whitmer was identified as successor to Smith, should he fall, and the Presidency of the High Priesthood at Kirtland began to be referred to as the First Presidency. The reason for the change of reference was no doubt the anticipation of other presidencies, like the Zion presidency (July 1834). The identifier “First” left no doubt which group was referred to. A number of documents was back-written to include the new name. All understood that the First Presidency was the Presidency of the High Priesthood (of the Church). However, in this case, the terminology was not applied to Smith’s apostolic successors. The apostles were not identified with high priesthood directly (though they were called the traveling high council). Later Church administrations have sometimes ignored and sometimes claimed the title, Presidency of the High Priesthood.

In anticipation of the temple in Kirtland and Joseph Smith’s removal to Far West, Missouri, a close cooperation, an interleaving of officers, began between the Missouri and Ohio presidencies and councils. The Ohio high council might operate with any of the presidents or assistants and any twelve of the twenty-four councilors making up the council. With 1837 bringing dissent in both Ohio and Missouri, the cooperative equality disappeared and the term First Presidency was strengthened as the preferred term for the Presidency of the High Priesthood in Ohio. By 1841 the assistant presidents were again called counselors with one final exception, John C. Bennett, where the term now suggested a kind of reduced status.

Joseph Smith’s revelation of April 1835 was received at the request of the newly formed Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. This revelation was a shift in the textual landscape of Mormonism and created fascinating terminological fault lines.

8. The April 1835 Revelation

Joseph Smith founded two new priesthood groups early in 1835, the Twelve Apostles and the Seventy. While the apostles had been presaged before the formal organization of the Church (D&C 18), the first ordinations took place in February 1835. After their first attempt at functioning as a “traveling high council” and missionary force, the apostles felt the need for some more detailed direction regarding their standing and duty in the Church and asked Joseph Smith for this direction. Heber C. Kimball reminisced about the experience in his journal: “One evening when we were assembled to receive instructions, the revelation contained in the thirdsection of the Doctrine and Covenants, on priesthood was given to brother Joseph as he was instructing us and we praised the Lord.”

The text of the April 1835 revelation takes the form of a lecture, settling different questions, establishing terminology and the ordering of offices, and appealing to both Old Testament and New Testament-related narratives, a tradition with Joseph Smith, as well as combining several revelatory threads. The text of the revelation was printed as section 3 of the first edition of the Doctrine and Covenants in August 1835, a project that had been underway for some time. Since it will be more efficient to comment on a text form that is familiar, I will use the form of the currently printed version in the LDS Doctrine and Covenants corresponding to D&C 107:1–57.

1 There are, in the church, two priesthoods, namely, the Melchizedek and Aaronic, including the Levitical Priesthood.

2 Why the first is called the Melchizedek Priesthood is because Melchizedek was such a great high priest.

3 Before his day it was called the Holy Priesthood, after the Or der of the Son of God.

4 But out of respect or reverence to the name of the Supreme Being, to avoid the too frequent repetition of his name, they, the church, in ancient days, called that priesthood after Melchizedek, or the Melchizedek Priesthood.

5 All other authorities or offices in the church are appendages to this priesthood.

6 But there are two divisions or grand heads—one is the Melchizedek Priesthood, and the other is the Aaronic or Levitical Priesthood.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of this passage in modern ecclesial Mormonism. One hundred and twenty years later, it was still at work as it redefined the liturgy of ordination. Conceptually the revelation establishes two authority “pools” from which all Mormon priesthood offices are drawn. These pools are the Melchizedek Priesthood and the Aaronic Priesthood. This revelation marks the first time this revised architecture appears in detail. The remark about the Levitical priesthood is curious, since it folds the order into the Aaronic pool, while the Old Testament suggests a hierarchical difference. However, it is certainly a nod to the Mosaic era, where the Levites and the family of Aaron formed two different priestly castes. The revelation formalized a trend in the referential struggle to allow a way to speak both of groups of offices as a superset of particular officers and of individual ranks in the system. Terms like “Melchizedek High Priesthood” were being used at this period, along with other hybrids, to get some flexibility of language. Even with the April revelation that language would continue to evolve. Tracing and making useful sense of the way the rank and file spoke of Mormon authority in these early years are a frustrating and probably unhelpful enterprises in trying to draw conclusions about “doctrine.” The best that can be said is referential language had not settled into a uniform lexicon. The April revelation represents a codification of developing semantic clusters and, by the beginning of the twentieth century, a restrictive and solidifying scheme, though sometimes exegetes would force seams of historical meaning to appear consistent.

7 The office of an elder comes under the priesthood of Melchizedek.

This short sentence addressed a question resulting from early practice and revelation. It seems familiar from D&C 84, but recall that the system there was quite different. Its import is that the office of elder is no longer a tag-along to the high priesthood. It formally sections out a bit of the reminted category, “Melchizedek Priesthood.”

8 The Melchizedek Priesthood holds the right of presidency, and has power and authority over all the offices in the church in all ages of the world, to administer in spiritual things.

9 The Presidency of the High Priesthood, after the order of Melchizedek, have a right to officiate in all the offices in the church.

10 High priests after the order of the Melchizedek Priesthood have a right to officiate in their own standing, under the direction of the presidency, in administering spiritual things, and also in the office of an elder, priest (of the Levitical order), teacher, deacon, and member.

11 An elder has a right to officiate in his stead when the high priest is not present.

12 The high priest and elder are to administer in spiritual things, agreeable to the covenants and commandments of the church; and they have a right to officiate in all these offices of the church when there are no higher authorities present.

Some of the important phrases here are “The Presidency of the High Priesthood, after the order of Melchizedek” and “High priests after the order of the Melchizedek Priesthood.” By themselves they are not new expressions in Mormon discourse, but in the context of verses 1–5 they take on a new meaning. The high priesthood is no longer the fount from which the offices of elder and bishop spring according to the April revelation, and the high priesthood itself lives under the umbrella of the Melchizedek Priesthood.The ordering phrase suggesting that an elder has the right to officiate when a high priest is not present is an artifact of the official pecking order of D&C 20. This ordering of offices effectively depends on the principle of common consent and later practice seems to negate it. The early Church struggled enough with traveling ministries interfering with local Church administration, reorganizing branches, or contravening the instructions of local officers, to the point where appointed ecclesial leadership often trumped office ordering. That, and the desire to flatten this “latent authority,” led to a certain demotion of the high priesthood.

13 The second priesthood is called the Priesthood of Aaron, because it was conferred upon Aaron and his seed, throughout all their generations.

14 Why it is called the lesser priesthood is because it is an appendage to the greater, or the Melchizedek Priesthood, and has power in administering outward ordinances.

15 The bishopric is the presidency of this priesthood, and holds the keys or authority of the same.

16 No man has a legal right to this office, to hold the keys of this priesthood, except he be a literal descendant of Aaron.

17 But as a high priest of the Melchizedek Priesthood has authority to officiate in all the lesser offices, he may officiate in the office of bishop when no literal descendant of Aaron can be found, provided he is called and set apart and ordained unto this power by the hands of the Presidency of the Melchizedek Priesthood.

Here we have a new definition of “lesser priesthood.” It no longer refers just to the office of priest, as it does in D&C 84 for example, and the offices of deacon and teacher are not styled as appendages to it. Instead, all are now drawn from the pool of the Aaronic order. An important addition here is the office of bishop. It is now a part of the Aaronic order, not an appendage to the high priesthood. Moreover, the Old Testament notion of patrilineal heritage attaches to the bishopric. If a literal descendent of Aaron can be identified, he may officiate without being ordained to the high priesthood (which may still officiate in the other offices). During Joseph Smith’s lifetime, no man was identified by the presidency as being in this category. Its meaning was not practical, and its religious value lies in the linkage it creates to the ancient pre-Christian world. In Joseph Smith’s view, the “priest hoods” of all former dispensations would be included in this last restoration.

One more item related to the terminology of this portion of the revelation: the presidency of the Aaronic Priesthood. This has an interesting connection to the 1832 revelations contained in D&C 84. With the priesthood architecture of the 1832 revelations, the priest is a kind of parent office, the teacher and deacon offices characterized as outgrowths of the priestly office. By the 1870s at least, some had started to use the language of verse 15 above to consider the bishop the “President of the Aaronic Priesthood.”This kind of speech is curious. Focusing one eye on 1832 and another on 1835, there is a perfectly rational explanation for such language. But, this bridge between the two worlds is unstable, and then paradoxical, in a broad sense. On the other hand, crossing that bridge brings into view the office of a functioning bishop in current praxis: he is presiding priest(in 1835, no longer part of the high priesthood) and presiding high priest at the same time. In 1832 “bishop” was seen as an outgrowth of the high priesthood—though Partridge was ordained before the high priesthood was announced. This figures into the 1835 revelations and redactions in complex ways.

18 The power and authority of the higher, or Melchizedek Priesthood, is to hold the keys of all the spiritual blessings of the church—

19 To have the privilege of receiving the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven, to have the heavens opened unto them, to commune with the general assembly and church of the Firstborn, and to enjoy the communion and presence of God the Father, and Jesus the mediator of the new covenant.

20 The power and authority of the lesser, or Aaronic Priesthood, is to hold the keys of the ministering of angels, and to administer in outward ordinances, the letter of the gospel, the baptism of repentance for the remission of sins, agreeable to the covenants and commandments.

Joseph Smith repeated the quotation from Hebrews 12 in sermons touching on a maturing temple concept and its ritual. In a sense, this passage affirms that the ideas of D&C 84 are still valid, simply expressed in a new context. In an important way, the revelation takes what was once the sole province of the high priesthood, and spreads it out into the new authority pool, the Melchizedek Priesthood. This language is clearly reflective of the book of Hebrews as a whole and Smith saw the book as particularly useful and important in a number of ways.

21 Of necessity there are presidents, or presiding officers growing out of, or appointed of or from among those who are ordained to the several offices in these two priesthoods.

22 Of the Melchizedek Priesthood, three Presiding High Priests, chosen by the body, appointed and ordained to that office, and upheld by the confidence, faith, and prayer of the church, form a quorum of the Presidency of the Church.

The Presidency of the High Priesthood is molded into the new formalism with a new title: the Presidency of the Church or, as it had already become known, the First Presidency.This is both a new and a continuing construct.

23 The twelve traveling councilors are called to be the Twelve Apostles, or special witnesses of the name of Christ in all the world—thus differing from other officers in the church in the duties of their calling.

24 And they form a quorum, equal in authority and power to the three presidents previously mentioned.

While early practice following this revelation evidences otherwise, the language here suggests that we look back to the twelve counselors in the court of the president of the high priesthood. Indeed, so did the establishment of the high council in 1834. In fact, the apostles are a traveling high council as later text announces. The word “quorum” appears again, which now replaces less specialized terms used in earlier revelations. The apostles as a group are equal in authority to the presidency “quorum.” The word “equal” here has never been taken seriously, except in terms of succession—with the possible exception of the financial difficulties during the Wilford Woodruff administration.

25 The Seventy are also called to preach the gospel, and to be especial witnesses unto the Gentiles and in all the world—thus differing from other officers in the church in the duties of their calling.

26 And they form a quorum, equal in authority to that of the Twelve special witnesses or Apostles just named.

27 And every decision made by either of these quorums must be by the unanimous voice of the same; that is, every member in each quorum must be agreed to its decisions, in order to make their decisions of the same power or validity one with the other—

28 A majority may form a quorum when circumstances render it impossible to be otherwise—

29 Unless this is the case, their decisions are not entitled to the same blessings which the decisions of a quorum of three presidents were anciently, who were ordained after the order of Melchizedek, and were righteous and holy men.

The seventy are addressed and again the word equal is applied to their standing in regard to the apostles. By transitivity, the seventy are equal to the presidency, but again, the meaning is typically seen as relevant only in terms of succession. The Church presidency is here given an ancient (Old Testament) basis. This meshing of Old and New Testaments was again typical of Joseph Smith’s ideas, later characterized by him as “welding” former revelatory epochs into one.

30 The decisions of these quorums, or either of them, are to be made in all righteousness, in holiness, and lowliness of heart, meekness and long suffering, and in faith, and virtue, and knowledge, temperance, patience, godliness, brotherly kindness and charity;

31 Because the promise is, if these things abound in them they shall not be unfruitful in the knowledge of the Lord.

32 And in case that any decision of these quorums is made in unrighteousness, it may be brought before a general assembly of the several quorums, which constitute the spiritual authorities of the church; otherwise there can be no appeal from their decision.

The judicial character of these groups is hinted at here, and also a new judicial body is founded, the “several quorums.” The meaning here is vague and has never been tested, although it could refer to the “solemn assembly” motif. Perhaps it also appears in the approval schemes of new policy or revelation, as in the 1978 priesthood change.A group like this functioned in Kirtland for a time during 1836, where “the several quorums for Church business” constituted a general quorum or council. In that case it included the presidencies of Kirtland and Far West, the two high councils, the apostles (as traveling high council), the two bishoprics, and the seven presidents of the seventies.

33 The Twelve are a Traveling Presiding High Council, to officiate in the name of the Lord, under the direction of the Presidency of the Church, agreeable to the institution of heaven; to build up the church, and regulate all the affairs of the same in all nations, first unto the Gentiles and secondly unto the Jews.

34 The Seventy are to act in the name of the Lord, under the direction of the Twelve or the traveling high council, in building up the church and regulating all the affairs of the same in all nations, first unto the Gentiles and then to the Jews;

35 The Twelve being sent out, holding the keys, to open the door by the proclamation of the gospel of Jesus Christ, and first unto the Gentiles and then unto the Jews.

The authoritative ordering not implied in the earlier text is given here. Functionally, the presidency directs the apostles, who direct the seventies in turn. Actual praxis has never been that pure, however.

36 The standing high councils, at the stakes of Zion, form a quorum equal in authority in the affairs of the church, in all their decisions, to the quorum of the presidency, or to the traveling high council.

The high councils en masse form a quorum. There are possible alternate readings (each high council forms a quorum, etc.), but intentionally, this one is suggested by other revelations dis cussed later, and text to follow. Never truly tested as an issue of government, it could be interpreted as a safety valve, available if the unthinkable happened.

37 The high council in Zion form a quorum equal in authority in the affairs of the church, in all their decisions, to the councils of the Twelve at the stakes of Zion.

This curious passage seems to place the Zion high council on a level, by themselves, with the Twelve Apostles (and it also tends to work against the alternate interpretation for high councils above). Since there is no designated Zion high council at present, the point is moot perhaps, but interesting.Moreover, the apostles, as a body, were, in this era, barred from interfering in stakes. That would begin to change in Nauvoo as Joseph Smith began to trust Brigham Young and the apostles, removing their activity restrictions and placing many of them in his inner circle in terms of liturgy, polygamy, and politics.

38 It is the duty of the traveling high council to call upon the Seventy, when they need assistance, to fill the several calls for preaching and administering the gospel, instead of any others.

39 It is the duty of the Twelve, in all large branches of the church, to ordain evangelical ministers,as they shall be designated unto them by revelation—

40 The order of this priesthood was confirmed to be handed down from father to son, and rightly belongs to the literal descendants of the chosen seed, to whom the promises were made.

The canonical regulation of Church “patriarchs” is here. Joseph Smith allowed that the New Testament “evangelist” was equivalent to the Mormon office of patriarch. The revelation indicates that they are to be called by the apostles in all large branches of the Church.The patrilineal descent trope already mentioned in regard to bishops reappears here for patriarchs but as a continuance of the Genesis 1–11 ancients. It was never enforced except in the case of descendants of Joseph Smith Sr. relative to the “Pa triarch to the Church,” a now deprecated office. The text telegraphed more apostolic intrusion in established Church zones. The patriarchal ordinations created important emotional loyal ties. Those loyalties were influential among Latter-day Saints on a social level beyond formal Church structure.

41 This order was instituted in the days of Adam, and came down by lineage in the following manner:

42 From Adam to Seth, . . .

53 Three years previous to the death of Adam, he called Seth, Enos, Cainan, Mahalaleel, Jared, Enoch, and Methuselah, who were all high priests, with the residue of his posterity who were righteous, into the valley of Adam-ondi-Ahman, and there bestowed upon them his last blessing.

54 And the Lord appeared unto them, and they rose up and blessed Adam, and called him Michael, the prince, the archangel.

55 And the Lord administered comfort unto Adam, and said unto him: I have set thee to be at the head; a multitude of nations shall come of thee, and thou art a prince over them forever.

56 And Adam stood up in the midst of the congregation; and, notwithstanding he was bowed down with age, being full of the Holy Ghost, predicted whatsoever should befall his posterity unto the latest generation.

57 These things were all written in the book of Enoch, and are to be testified of in due time.

An excerpt here or perhaps a condensation from the Enoch mythos first explored in the early 1830s, the text gives the lineal descent of the ancient patriarchal authority that provides a background mythology for the 1834 office of patriarch. The revelation is linked to a vision of Adam-ondi-Ahmanand it suggests the compiled nature of the April revelation. These priesthood genealogies of the Aaronic (D&C 68, 107), patriarchal (D&C 107), and high priesthoods (D&C 84) not only provide for, or subscribe to, the legitimacy of ancientness, they form a part of the narrative of gathering both in holy communities and in the Elijah-mediated chain of salvation.

The effect of the April 1835 revelation is difficult to fully quantify. It gradually changed the discursive world of Mormonism in many important ways. Perhaps the most curious part about the April revelation was not internal, but was the decision of the 1835 editorial committee to include the November 11, 1831, revelation as a continuing text in publication, even leaving in the special directive to Zion (and probably directed to the sometimes recalcitrant Partridge in 1831). The semantic tension between the two texts is evident. But there were certain important elements of the November revelation not found anywhere else. Smith was sensitive to charges in the past that he produced revelations at need. Preserving the text of the November revelation was important to all concerned, and useful given the rigid nature of the faith of many.

9. Holy Protologies—Holy Descendants

As noted already, patrilineal descent of bishops had no practical discernible application, so what is its purpose? While it may be interpreted as offering the office of bishop as a restoration from the ancient world, securing Mormon exceptionalism in yet another way, it also offers a look at the way early Latter-day Saints saw themselves. Their religion was not just a reappearance of the ancient order of things. The Saints were descendants of the ancients in body as well as in spirit. The idea that they might be seen as children of Aaron (an image that appears prominently in the September 1832 revelations in both a literal and an adoptive sense) conferred a kind of immortality that was strengthened through Joseph’s career. Modern biology tells us that if Aaron’s line didn’t die out, then we are all descended from him—but patriarchal blessings continue the powerful adoption theology from the earliest years of the restoration.

The 1832 and 1835 revelations each capture within them holy genealogies for Mormon priesthoods and use those protological foundations to regularize and sacralize office. The September 1832 revelations linked the high priesthood to and simultaneously legitimized the Mosaic dispensation by providing a way for the great prophet to fit into an authoritative pathway. Such pathways formed a vital part of the message of Mormonism. Ordination to the ministry was not by the authority of the community—through believer priesthood—but by legal actors legitimized by ordination through a traceable line of predecessors: a line that had either to terminate with the first man, Adam, or God himself. The great Mormon apologists found in this the justification for Mormonism. The linkage to the ancient legal actors was lost. It could only be reestablished through an angelology—the Eliasmotif—that allowed the ancients to return, bringing with them a restoration of lost connection to the Adamic era, a continuing theme that broadened, solidified, and flowered with the Elijah doctrine. One of the tributaries to the 1835 revelation rewrote the office of priest as Aaronic and the office of bishop as the high priesthood of the Aaronic order, giving the bishopric an ancient legitimacy that simultaneously matched and restructured the 1832 “priesthood” in the office of bishop. The 1834 patriarch, Joseph Smith Sr., found his holy genealogy and legitimacy within the genealogy of Genesis 1–11 as the 1835 revelation read his office back to the Adamic generation. Each of these founding myths and protocols placed the various branches of Mormon priesthood in a landscape that did not simply mimic the King James language of ancient office but provided both justification and legal foundation for the new Mormon revelation. Inevitably this drew on and then emphasized the “priesthood restoration” narratives for angelic encounters with John the Baptist, Peter, James and John, Moses, “Elias” and Elijah.This sets the stage to consider how Joseph Smith and his fellow editors treated the text of the November 11 revelation when they published it as “part 2” of the April 1835 revelation in the first edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.

10. Eras in Collision—Editing the November 11, 1831, Revelation

When D&C 107 was printed (as D&C 3) in late summer 1835, it contained both the April 1835 revelation and the November 11, 1831, revelation conjoined. However the terminology and priesthood architecture of the two revelations were not the same. Meanwhile, the November 11, 1831, revelation was heavily modified in D&C 107 to reflect at least some of the organizational development in the bishopric and president of the high priesthood offices as well as the new office of seventy. But the terminological inconsistencies were not made coherent. The 1835 publication committee felt some urgency in having the November 1831 revelation in print, at least in modified form. It provided direction in a number of circumstances, integrated new priesthood offices (apostles, seventies) with old (Presidency of the High Priesthood), and provided a platform to disseminate several new revelations effecting organizational topology, which were essentially unknown or at least unpublished up to that point.

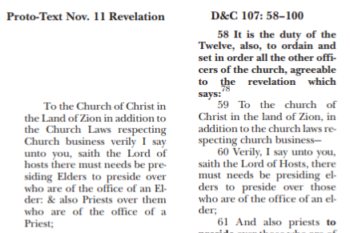

In the excerpts below, the portions of the D&C version of the November 11 revelation that are new are shown in bold, while omitted portions of the November 11 revelation are highlighted in italics. Pronoun changes and accidentals are generally ignored. To make reference easier, the text and verse numbering from the current (1981) LDS Doctrine and Covenants is used as comparator to the 1831 proto-text.

| Proto-Text Nov. 11 Revelation To the Church of Christ in the Land of Zion in addition to the Church Laws respecting Church business verily I say unto you, saith the Lord of hosts there must needs be presiding Elders to preside over who are of the office of an El der: & also Priests over them who are of the office of a Priest; & also Teachers over them who are of the office of a Teacher, & from Teacher to Priest, And also the deacons; wherefore from Deacon to Teacher, & from Teacher to Priest, & from Priest to Elder; severally as they are appointed, according to the Church Articles & Covenants: then cometh the high Priest hood, which is the greatest of all: wherefore it must needs be that one be appointed of the high Priest hood to preside over the Priest hood: & and he shall be called President of the | D&C 107: 58–100 58 It is the duty of the Twelve, also, to ordain and set in order all the other officers of the church, agreeable to the revelation which says: 59 To the church of Christ in the land of Zion, in addition to the church laws respecting church business— 60 Verily, I say unto you, saith the Lord of Hosts, there must needs be presiding elders to preside over those who are of the office of an elder; 61 And also priests to preside over those who are of the office of a priest; 62 And also teachers to preside over those who are of the office of a teacher, in like manner, and also the dea cons— 63 Wherefore, from dea con to teacher, and from teacher to priest, and from priest to elder, severally as they are appointed, according to the covenants and commandments of the church. 64 Then comes the High Priesthood, which is the greatest of all. 65 Wherefore, it must needs be that one be appointed of the High Priesthood to preside over the priesthood, and he shall be called President of the High Priesthood of the Church; 66 Or, in other words, the Presiding High Priest over the High Priesthood of the Church. 67 From the same comes the administering of ordinances and blessings upon the church, by the laying on of the hands. 68 Wherefore, the office of a bishop is not equal unto it; for the office of a bishop is in administering all temporal things; 69 Nevertheless a bishop must be chosen from the High Priesthood, unless he is a literal descendant of Aaron; 70 For unless he is a lit eral descendant of Aaron he cannot hold the keys of that priesthood. 71 Nevertheless, a high priest, that is, after the order of Melchizedek, may be set apart unto the ministering of temporal things, having a knowledge of them by the Spirit of truth; 72 And also to be a judge in Israel, to do the business of the church, to sit in judgment upon transgressors upon testimony as it shall be laid before him according to the laws, by the assistance of his counselors, whom he has chosen or will choose among the elders of the church. 73 This is the duty of a bishop who is not a literal descendant of Aaron, but has been ordained to the High Priesthood after the order of Melchizedek. 74 Thus shall he be a judge, even a common judge among the inhabitants of Zion, or in a stake of Zion, or in any branch of the church where he shall be set apart unto this ministry, until the borders of Zion are enlarged and it becomes necessary to have other bishops or judges in Zion or elsewhere. 75 And inasmuch as there are other bishops appointed they shall act in the same office. 76 But a literal descendant of Aaron has a legal right to the presidency of this priesthood, to the keys of this ministry, to act in the office of bishop in dependently, without coun selors, except in a case where a President of the High Priesthood, after the order of Melchizedek, is tried, to sit as a judge in Israel. 77 And the decision of either of these councils, agreeable to the commandment which says: 78 Again, verily, I say unto you, the most important busi ness of the church, and the most difficult cases of the church, inasmuch as there is not satisfaction upon the deci sion of the bishop or judges, it shall be handed over and car ried up unto the council of the church, before the Presidency of the High Priesthood. 79 And the Presidency of the council of the High Priest hood shall have power to call other high priests, even twelve, to assist as counselors; and thus the Presidency of the High Priesthood and its counselors shall have power to decide upon testimony according to the laws of the church. 80 And after this decision it shall be had in remembrance no more before the Lord; for this is the highest council of the church of God, and a final decision upon controversies in spiritual matters. 81 There is not any person belonging to the church who is exempt from this council of the church. 82 And inasmuch as a Presi dent of the High Priesthood shall transgress, he shall be had in remembrance before the common council of the church, who shall be assisted by twelve counselors of the High Priesthood; 83 And their decision upon his head shall be an end of controversy concerning him. 84 Thus, none shall be exempted from the justice and the laws of God, that all things may be done in order and in solemnity before him, according to truth and righteousness |

The bulk of the textual changes here have to do with the information on patrilineal descent of the bishopric. The text links the family of Aaron with the bishop, who fills the role of the Mo saic-Aaronic high priest, an office requiring lineal descent from Aaron. The rules here are reminiscent of the Levitical rules for the tabernacle priest. Observe also the substitution of the word “council” for “court.” That same substitution eventually took place in Church instructions on Church courts in the 1990s.

Next, consider the remainder of the revelation and the corresponding changes in the 1835 text. The second part of the November 11, 1831, revelation/D&C 107 was altered in interesting ways when published in 1835 and like the first part, these changes also reflect otherwise unknown revelation(s).

| Proto-Text of November 11, 1831 A few more words in addition to the Laws of the church. And again, verily I say unto you, the duty of the president over the office of a Deacon, is to preside over twelve Deacons, to set in council with them, & to teach them their duty, edifying one another as it is given according to the covenants. And also the duty of the president over the office of the Teachers, is to preside over twenty four of the Teachers, & to set in council with them, & to teach them the duties of their office as given in the covenants. Also the duty of the president over the priesthood is to preside over forty eight priests, & to set in council with them, & to teach them the du ties of their office, as given in the covenants. And again the duty of the President over the office of the Elders, is to preside over ninety six Elders, & to set in council with them, & to teach them ac cording to the covenants. And again the duty of the pres ident of the office of the High Priesthood, is to preside over the whole church, & to be like unto Moses. behold here is wisdom: yea, to be a Seer, a revelator, a transla tor, & prophet, having all the gifts of God, which he bestoweth upon the head of the chuch: Wherefore now let every man learn his | D&C 107:85–100 85 And again, verily I say unto you, the duty of a president over the office of a deacon is to preside over twelve deacons, to sit in council with them, and to teach them their duty, edifying one another, as it is given according to the covenants. 86 And also the duty of the president over the office of the teachers is to preside over twenty-four of the teachers, and to sit in council with them, teaching them the duties of their office, as given in the covenants. 87 Also the duty of the president over the Priesthood of Aaronis to preside over forty-eight priests, and sit in council with them, to teach them the duties of their office, as is given in the covenants— 88 This president is to be a bishop; for this is one of the duties of this priesthood. 89 Again, the duty of the president over the office of elders is to preside over ninety-six elders, and to sit in council with them, and to teach them according to the covenants. 90 This presidency is a distinct one from that of the seventy, and is designed for those who do not travel into all the world. 91 And again, the duty of the President of the office of the High Priesthood is to preside over the whole church, and to be like unto Moses— 92 Behold, here is wisdom; yea, to be a seer, a revelator, a translator, and a prophet, having all the gifts of God which he bestows upon the head of the church. 93 And it is according to the vision showing the order of the Seventy, that they should have seven presidents to pre side over them, chosen out of the number of the seventy; 94 And the seventh president of these presidents is to pre side over the six; 95 And these seven presi dents are to choose other sev enty besides the first seventy to whom they belong, and are to preside over them; 96 And also other seventy, until seven times seventy, if the labor in the vineyard of necessity requires it. 97 And these seventy are to be traveling ministers, unto the Gentiles first and also unto the Jews. 98 Whereas other officers of the church, who belong not unto the Twelve, neither to the Seventy, are not under the responsibility to travel among all nations, but are to travel as their circumstances shall allow, notwithstanding they may hold as high and responsible offices in the church. 99 Wherefore, now let every man learn his duty, and to act in the office in which he is ap pointed, in all diligence. 100 He that is slothful shall not be counted worthy to stand, and he that learns not his duty and shows himself not approved shall not be counted worthy to stand. Even so. Amen. |

The compiled versions of the November 1831 and April 1835 revelations served as a foundation for much of LDS organization and became a litmus test for change and expansion.

11. Kirtland and Missouri Dissent and Canonical Modifications

D&C 107 was a long time in the making and contains many separate revelations woven together into a whole. Witness: The November 11 revelation, itself perhaps two separate revelations, the vision of the Seventy, the vision of Adam, the esoterica of bishops, the “Enoch” text and others (see Appendix 1 for a stemmatic treatment). The story is one worth telling, not only to understand the process of revelation, but also to understand the way Latter-day Saints speak and how that speech and its understanding were effected by the processes of textual influence.

In spite of the publication of the November 11, 1831, revelation as a “part 2” of D&C 107 in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants, that was not the end of it. The trial procedures for the president of the high priesthood that appear in the November 1831 revelation (or as it was altered in D&C 107, “a” president of the high priesthood) were given in terms of the common council: a bishop plus twelve high priests selected for the purpose.

Two kinds of issues drove the evolution of this concept:

1. The deterioration of the Kirtland economy and the increasing criticism of Joseph Smith for the failure of the Mormon “bank,” led to charges of financial duplicity from apostles Lyman Johnson and Orson Pratt.

2. In Far West, Missouri, the excommunication of Oliver Cowdery (a member of the Presidency of the High Priesthood) took place. Cowdery claimed the court was illegal, but it appears that the bishop at Far West (Edward Partridge) did take part.

With a first brush with Church discipline and the possibility of others looming, Joseph Smith sought clarification. The result was three revelations, given January 12, 1838. These revelations may have been relevant to the Cowdery case, but they were not reported to the Church at large until July 6, 1838. Since they are relevant to D&C 107, I give two of them here: