Articles/Essays – Volume 26, No. 2

Each in Her Own Time: Four Zinas

A family story provides an image which well expresses Zina Young Card. On the portico over the main entrance to the Lion House, built by her father Brigham Young for his large family, rests the stone lion, couchant, which gave the building its name. The sculpture served as railing to a second-floor balcony, accessible from the south rooms. As the story goes, mother Zina Young was looking for the active little girl, calling through the corridors, “Ziney! Ziney,” as she went.

“Here I am, Mama,” came the answer, and the fearful mother followed the voice through the curtained French doors to where the child sat proudly astride the lion, a precarious twenty feet above the ground below. “Ziney” clambered safely off the beast, and the crisis passed. But the image remains, the daughter of the ruling household astride the lion emblematic of her father as he was perceived by his followers. If Brigham Young was the “lion of the Lord,” young Zina was certainly his whelp.

There was something imperious in the character of Zina Presendia Young Williams Card. Her approach to her family, her co-religionists, her society, seems, if not regal, certainly aristocratic. In childhood she felt herself a particular favorite, even though she was one of thirty-one of her father’s daughters, ten of whom were born within three years of her. Of her mother’s treatment of Zina, her only daughter, Emmeline B. Wells, wrote “no princess of royal blood was ever more fondly beloved, or more tenderly cared for than this little one.” This third in a series of six Zinas in one family fits in the succession of mothers and daughters each of whom provides a window on the lives of her contemporary Mormon sisters, on Mormon women generally.

More than a decade ago, listening to Jan Shipps’s lecture, “In the Presence of the Past,” later revised and included in her Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, I acknowledged with her the vast differences between nineteenth- and twentieth-century Mormonism. My further study of the lives and experiences of Mormon women leads me to conclude that not only century by century, but generation by generation the religion changes. However stable the theology of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints may have been, or not been, experiential Mormonism has been radically diverse for each generation. It is easily evident that no two generations of Latter-day Saints experience the same church and culture.

Seven generations of many families have participated now in the Mormon movement. What the differences have been, and how they have affected individual lives is a question far too involved for one person’s study. But let me here make a tenuous beginning, narrowing the field for an initial glimpse by dealing with one gender, female, and one line of descent, the first four Zinas of the Baker-Huntington-Young-Card line.

Why these? Because each in her time was of her time. Because of, or despite, her originality, her personal authenticity, each represented her generation of Mormon life and experience. Born successively in 1786,1821, 1850, and 1888, they passed through the major phases of Mormon history: conversion, gathering, migration, settlement, outward colonization, diaspora, and re-gathering. The story continues: there are two more Zinas, both still living, who in similar ways represent twentieth-century movements. This essay will leave them to finish out their lives, however, and a historian of the twenty-first century to discover their parallels.

Let me first provide a thumbnail sketch of each woman in her turn. Like her daughters after her, Zina Baker was born on what was then the frontier, the village of Plainsfield on the New Hampshire side of the border near Windsor, Vermont. She was a twin, of her mother’s third of ten birthings. At the age of twenty, Zina married William Huntington, whose parents had already migrated the next step westward, to Watertown near Lake Ontario in northern New York. Of their ten children, seven survived. Zina Diantha was their eighth child, and last girl.

When the Huntingtons converted to Mormonism in 1835, Zina Baker, as we shall call this first Zina, was forty-nine years old. Her childbearing complete, her grandchildren were growing in number. Zina Diantha was then fourteen. Selling the farm, the Huntingtons followed the church to Kirtland, Ohio, where the family participated in the settlement of the town and the dedication of the temple. Through a land scam, William and Zina lost their property and had to borrow of Oliver Snow to travel with that family to Missouri. Not a year later the Huntingtons were again crossing Missouri, this time back to Quincy, Illinois, then to Nauvoo. By then they were depleted in health as well as wealth; mother Zina Baker died and was the third Mormon buried in the new gathering place.

Of his sister Zina Diantha, her younger brother Oliver remembered, “Zina kept house for us, and a good mother she was to us all.” Their father William, with three children yet at home, married and merged families with Edward Partridge’s widow Lydia, who had five. Six months later, in 1841, Zina Dinatha married Henry Bailey Jacobs and bore Zebulon in 1842. In the meantime she was sealed for eternity to Joseph Smith but remained wife to Henry. In Nauvoo Zina participated in the early development of the Relief Society, became fast friends with many of the women there, and developed a reputation for her healing gifts.

As the Saints prepared to leave Nauvoo and the temple, her original sealing to Joseph Smith was confirmed, and at the same time, Henry Jacobs present and approving, she was sealed for time, as were others of Joseph’s wives, to Brigham Young. With Henry she began the trek west, giving birth on the Chariton River to a son whom they named for his birthplace. From Mount Pisgah, Henry went on a mission to Britain; on his return he married his second wife Aseneth, and Zina became in fact as well as by sealing a wife to Brigham Young.

Once in Utah, Zina gave birth in 1850 to her own daughter Zina, the child “Ziney” of the lion’s back, best known as Zina Card. She was her mother’s only child by Brigham Young. Zina Diantha reared her, her two Jacobs boys, and, on the death of their mother in 1858, four children of Brigham Young and Clara Ross. Once the children were raised, Zina Diantha increased her work among the women, extending her healing services well beyond the walls of the Lion House. She served as counselor and traveling companion to her sister wife Eliza R. Snow, and in 1888 succeeded Sister Snow as general president of Relief Society and matron of the Salt Lake temple, which offices she held until she died in 1901.

Young “Ziney” grew up in her father’s household, one of his “big ten” daughters in the Lion House. Educated with her sisters, she acted from age thirteen on in the Salt Lake Theatre. There she met and married the treasurer of the theatre, one of her father’s scribes, Thomas Williams. He was forty, and already twice married; she was eighteen.

Two years later their son Sterling was born and, in another three, Thomas. He had not yet turned one when his father died, leaving Zina, with her mother’s help, to raise the boys. She enrolled at Brigham Young Academy in Provo, where she soon became a faculty member, then head of the young ladies’ department of the school.

In 1884, at the height of the raid against polygamists, she married Charles Ora Card, president of Cache Stake in Logan, Utah. They spent much of the next three years “on the underground,” he to avoid arrest for “unlawful cohabitation,” and she to avoid having to testify against him (she bore Card’s son Joseph in 1885). In 1887 Zina joined Card in his settlement of the Southern Alberta colony which became Cardston. There, on 12 June 1888, her own Zina was born, “another new settler for the Mormon settlement on Lee’s Creek,” as the Lethbridge News reported, and later one more son, Rega. “Aunt Zina” Card was the unquestioned female leader of the Alberta colonies. Through her roles as wife to the community’s founder and president of the ward and later stake YLMIA, she directed much of the social and ecclesiastical life of the group; entertained distinguished visitors; and traveled to and from Utah to assist her mother in the Relief Society work.

In 1903, because of her husband’s failing health, Zina Card took him back to Logan, where he died in 1906. Once more widowed, Zina, with her three Card children, set up housekeeping again in Salt Lake City. There she became matron of the LDS College and travelled to wards and stakes as Primary board member. Eventually she became a worker in the Salt Lake temple.

In the meantime, her “little Zina” had met young Hugh B. Brown in Cardston. He followed the Cards to Logan, living in their home where, to support himself at Brigham Young College, he helped care for the aging Card. Following his mission to Britain, he became engaged to the twenty year-old Zina. They were married in 1908, just over a hundred years from the marriage of our first Zina and her William.

Zina Brown’s role was immediately circumscribed by her husband’s entrepreneurial activities: retail sales, investments, ranching, insurance, and eventually the study and practice of law. His church and civic responsibilities took him often from home. During both world wars Zina was left to care for home and family—they had eight children—while he served first in the Canadian Army, then as LDS servicemen’s coordinator. She served with him the third time, when he was called in 1937 to preside over the British Mission. In 1966, however, when Hugh was functioning in the First Presidency of the LDS church, Zina suffered a stroke. From then to her death, she was almost totally bedridden, her capacity for speech lost. She died in 1974.

So there they are, in brief outline, the first four Zinas. They share many common qualities, not the least of which is an overwhelming fondness of each for her mother: Zina Baker’s letters to her mother Dorcas back in New Hampshire are replete with pleading that she come visit; Zina Diantha was so distraught at the death of her mother that when her body was exhumed four years later, Zina was still in deep mourning; Zina Card was so close to her mother that, as well as living with her during her own first marriage, she had her come the more than 800 miles from Utah to Canada to attend her at the births of her children, and returned the visits for months at a time. As Emmeline B. Wells observed in a letter addressed to both in Canada, “in a certain sense you two, mother and daughter, are one.” And Zina Brown, even after her marriage, spent many weeks with her mother in Salt Lake City, beginning with her first Christmas as a wife. The pain of separation was reciprocated from mother to daughter: asked by Hugh if he might propose to her daughter, Zina Young Card replied, “You can’t have her. I won’t let her go back to Canada.”

That the women bonded so completely was not unusual in nineteenth century America, where women’s world was gender-contained, their clos est affections being expressed among their own sex. The twentieth-century-born Zinas would demonstrate a more modern sensibility which expects of marriage partners the emotional intimacy their fore mothers shared within their gender.

Documents extant demonstrate in each of these women the qualities archetypally attributed to the Mormon pioneer woman: enduring, hard working, bright, attractive (though the present age would probably find Zina Baker, as she wrote her family, grown too large), articulate, inventive, compassionate, possessed of great faith, able to lead in their own spheres, yet unquestioningly obedient to priesthood authority. To a woman they exemplified the nineteenth-century model of “true womanhood”: they were pious, pure, domestic, and submissive.

Controlling, in a sense, for those qualities, let us look now at the difference it made for each woman to have been born when she was, to have experienced that part of Mormonism that was available to her. Only a segment of each woman’s life can be treated in so small a space, but hopefully that much will suggest the larger issues and those which throw light on the history of Mormon women generally.

Begin with Zina Baker. She married and moved to New York in 1805, the year Joseph Smith was born in Vermont. Obviously there was no Mormonism to touch her as she began her adult life. Like the boy prophet, however, she was a seeker; like him, she took what of religion she could get in her sparsely populated neighborhood, including the revival fervor of the 1820s. Unlike him, however, she was of Presbyterian bent, and sought assurance of her “calling and election” through basically Calvinist paths. In as much detail as small space permits, I would like to trace her spiritual path, not only for what light it throws on Zina Baker as an individual, but because so many women who later joined with the Saints followed similar routes before confronting Mormonism.

A splendid correspondence extant contains the letters received by Zina’s mother Dorcas Baker between 1806 and 1831. Most are from Zina Baker Huntington herself, with some from William. In them one can find a gauge to the spiritual development of the two as they relate to the distant parents the state of their souls. The early letters, 1806 to about 1816, report not much denominational activity in Watertown; it is “a time of dullness as to religion.” Zina finds herself “growing stupid,” experiencing a time of spiritual dryness. Anticipating the approaching death of her sister, she writes to know whether Lina “felt resigned,” to the will of God. For herself, Zina is not sure: “I believe in some measure,” she writes, “and pray that my heart may not be deceived.” The War of 1812 intervenes, with battles at nearby Sacket’s Harbor; the family moves five miles to Burrs Mills, several children are born, William’s fortunes dip, and little is said of religion, except to observe again “a remarkable dying time,” a “general time of coldness.” Then, in 1817, a change comes in the letters. No general reformation, Zina writes, but “we have reason to bless God for a few drops of his grace and mercy.” The Calvinist process of sanctification, an inheritance from the Great Awakening, is still with Zina as she recounts William’s approach to conversion: “the Saviour of our souls… has opened the eyes of my husband to see his dreadful situation by nature and to realize his transgressions…” He “is about to join the Church,” having “obtained a hope” four months earlier. Caught in her belief that one can but wait upon God, Zina adds: “I think sometimes I am fitting for the approach of some great event, but hope I shall ever be prepared for all that awaits me, and ever feel reconciled to God’s will and rejoice in his government.”

William’s letters reflect his state of faith: “We have reason to hope that the latter day glory is drawing nigh.” Secure now in William’s affirmations, Zina in 1820 writes a brief sermon to her family, this time in the rhetoric of a preacher, suggesting that she has been hearing the language of the revivalists. By 1822, “there is revivals of religion all around us.” Picking up the fervor, Presendia, Zina and William’s eldest daughter, age eleven, “has experienced the saving change of heart, I believe,” Zina writes.

There comes creeping into Zina’s discourse a sense that one need not wait helplessly for the own good time of the Lord; that one may take a hand in one’s own salvation. Expecting her mother’s disapproval, she has at tended a Methodist revival: “The power of God was there,” she confesses. “I tell you the way is to labour yourself.” Nevertheless, in her last extant letter she affirms once more the Calvinist path of her spirit:

The Lord called me to look about myself last spring before the revival began and O, what a situation I found myself in. I felt almost in despair. Oh, what darkness I experienced, I cannot describe it. O, the goodness and mercy of God. . . His mercy has . . . made me feel deep repentance such as I thought I never felt…. I think, dear Mother, I can tell you that I never felt that deep work of grace in my heart before.

Throughout the letters, and from Zina Diantha’s later description, it is apparent that where William studies, listens, and eventually accepts, Zina moves from state to state, searching her own soul for signs of grace. Her testimony comes from within; her faith is in her sense of God’s presence.

One year from that last writing the Book of Mormon was published in Palmyra, a hundred miles away; four years after that, Mormon missionaries visited the Huntingtons, bringing the restored gospel, the one which William had sought in scriptures and Zina had anticipated through the spirit. But before then Zina’s letters had ceased. Zina Baker’s final process of conversion to Mormonism remains lost to us; we can only interpolate from her spiritual autobiography as traced here that her conversion came through the spirit; that having learned humility and an openness of soul, she was teachable to the new message, and, as her actions show, received it wholeheartedly.

It is theologically important for each person to have her own religious experience, and for her to find expression of that experience in ways learned from, and acceptable to, her co-religionists, to be validated in the eyes of other believers. Hence the same spirit which manifested itself to Zina Baker in terms of an inward calm when “Everything appears right and just and my feelings are such as my pen cannot describe” would lead Zina Diantha to express her faith in the gifts of the spirit, in tongues, interpretation of tongues, prophecy, and the healing gifts. A generation later still, Zina Card, reaching for her mother’s gifts, found them beyond her grasp until she was in circumstances similar to those her mother experienced in Winter Quarters and early Salt Lake City: surrounded in their wilderness isolation by a group of her sisters, and in need of assurance of God’s mindfulness. Accounts of blessing meetings, healings, and washing and anointings are found in the early Cardston Ward record, and Zina Card is central to the practice. Those gifts faded as the corporate church with its large wards and planned programs replaced the settlement communities, and Zina Brown found her chief expression in devotion to her husband and family, and service to them and to the church, which by the 1930s had spelled out a more formal and restrictive structure for women.

Zina Diantha became an adult in Mormon Nauvoo in one of the most exciting, most developmental, most troubled times of the church’s history. Her young husband Henry Bailey Jacobs was a charismatic, enthusiastic missionary and embryonic church leader. Dashing in dress and manner, he was happiest proselytizing, preaching, conducting the affairs of the kingdom at large. Content with her smaller sphere, Zina cared for young Zebulon, attended meetings, visited with other women, and carried on the usual household tasks of the day.

A diary recently unearthed by the sixth of the Zinas, my friend and near contemporary Zina Elizabeth Brown, provides a window on the young Zina Diantha from June 1844, just prior to the death of Joseph Smith, until August 1845, as anti-Mormon mobs are beginning the violence which will drive the Saints west the following spring. The picture it paints of the little family is one of uncertainty, poverty, sickness. Henry suffers twice in the year with bouts of the “chills and fever”; Zina is afflicted for ten days with a painful swelling in her face, an “ague” she calls it, which finally “dis charged wonderfully” when the skin broke; and three-year-old Zebulon contracts scarlet fever which continues to “prey uppon the child” for nearly three weeks. At other times Zina nurses others in her home: Apostle Amasa Lyman; a lone woman whom her brother William brought her; her brother Oliver; a child who eventually dies there.

The nursing service Zina offers seems to boost the family’s meager income, along with the school she teaches for three weeks, the spinning she does “to procure an honest living,” the sewing for sister Grible and others “until 12 o’clock at knight,” and the palmleaf hats she learns to braid. Even so there is not enough to eat: she prays blessings on Joseph Young for the gift of a pan of flour, affirming that “if God ever blesses us with means, may we go and do likewise.” She purchases a lot on which Henry plans to build a house, but short of “drawing the frame and stone for his house,” he never completes the task, and they move from place to place in the city. During the fifteen months of the diary Henry becomes a Mason; goes on two missions within the state; is ordained president of the 15th Quorum of Seventy and attends its meetings; accompanies Zina and Zebulon to Lima for the berry-picking; and goes “to the fencing school or sword exercise.” It is difficult to ascertain what else either spouse did; certainly there was more required of both to sustain life, but diarists typically do not elaborate on routine tasks.

Central to Zina’s concern in her diary, however, is her faith. Daily entries often end with small prayers of thanks or longer psalms of praise. She summarizes sermons from the “stand” and once or twice from Henry’s quorum meetings which she has attended. A most disconcerting note in the diary is an entry on 3 May 1845. Zina begins with a preamble which reads, “God onely knows my heart this day. The thoughts of my heart or the emotions of my minde causes my very head to acke.” Then follows the most discouraged of all her psalm-like sentiments:

O God be merciful unto me and let me find grace in Thine eyes and those that fear Thee. O save my sole from ruin, my body from destruction, for they handma[i]d feels to put her trust in Thee. Enlighten my minde and give my sole understanding. Let not my hart think evil, not my tongue speak vanity. O let the trew seed remain in my heart and bring forth much fruit.

The next day, Sunday, she notes “I am at home, not able to go to meting but God will be there, or his Speret, and O may the saints be edified. Amen.” Friday following she makes this enigmatic comment:

Never to be forgotten at 11 oclock, O then what shall I say. At or after 4 I went to sleep. O Lord have mercy uppon my Sole. Teache me the ways of eternal life. Give me that gift above all others. Behold this is the desire of my hart. Comfort us, yes, Henry in his trouble, for he has not repined a word. . . .

On 11 June Zina notes that Henry “went to see Pres. B. Young to be councel[ed] upon his and families situation.” She follows the notation with “O God be merciful unto us,…” linking her own fate to that of her husband.

On 2 February 1846, as the Saints were preparing to leave Nauvoo, Zina stood in the temple, with Brigham Young as proxy for Joseph Smith, to ratify her earlier sealing to Joseph Smith. Then she was sealed to Young “husband and wife for time.” “Henry B. Jacobs [present at the time] ex pressed his willingness that it should be so in presence of these witnesses.”

However less than ideal Zina’s and Henry’s marriage may have been, her dissatisfaction with her lot explains her sealing to the two prophets. And Young’s statements justifying a woman’s leaving her husband “if she can find a man holding a higher Priesthood than her husband that will take her” came much later. My reading of Zina’s accounts finds in her unwavering obedience, unquestioning faith in priesthood authority. “Hasten thy work O Lord in its time,” she wrote in her diary, “and may I be prepared to receive all Thy Words and Obey them, even thy Celestial Law and thy Name shall have the Honour and Glory.” She would have been sealed to Joseph Smith because he asked her to, and he was the prophet. What his reasons were, and why Jacobs consented, is another question for another time.

More frequent than references to her husband in the little diary are Zina’s accounts of women friends, those who visit her, and whom she visits—sisters, these, in kin or in faith, with whom she shares her work, her thoughts, her gifts. With them she continues a religious practice which will later bear the fruits of comfort and sisterly solidarity. Begun among the women in the early meetings of the Female Relief Society, the reception and exercise of pentacostal gifts was not limited to them. Speaking and singing in tongues, interpreting tongues, prophesying, blessing and healing one another, however, were more practiced among women than among men, and Zina, especially after learning their value to her sisters in the wilderness of Winter Quarters, would encourage their practice by her example for the rest of her life.

For most of her life, Zina was self sufficient, the one on whom others depended. After her mother’s death, she took over at home; when her father remarried, she moved to her older brother Dimick’s house, presumably to help Fanny with the children and the household. Married to Henry, she supported herself while he was on missions or involved in other things at Nauvoo. Left at Mt. Pisgah with her boy and new baby in her father’s care while Henry filled yet another mission, she then cared for her father until his death there. Alone of her family, she could but watch over her child and her newborn infant, hearing the wolves howling from the nearby grave yard, “those hungry monsters, who fain would have unsepulchred those sacred bones!” Finally Brigham Young sent his son-in-law Charlie Decker to collect the little family and bring them to Winter Quarters where she became part of “the girls,” Young’s plural wives, “welcomed by President Young into his family.”

Even in Utah, secure under Brigham’s roofs, Zina carried her share, teaching school, doctoring his family, and caring for his orphaned children. First, in the old “log row” in 1850 she gave birth to the daughter Brigham named for her mother. In 1856 they, as well as Zebulon and Chariton for a time, moved into the comfort of second-story rooms in the new Lion House, but once the children were grown, she left the Lion House to share a dwelling with her daughter, and then to live alone. Even then she took boarders to help with expenses. Perhaps such labor was not necessary for the wife of one of Utah’s richest men; perhaps it was just an independent streak in Zina herself, one that Brigham admired, and attempted to instill in Zina’s daughter. In any case, many women of her time exemplified it.

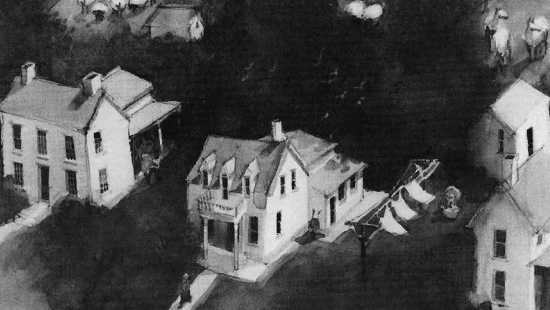

The children who grew up behind the stone walls of Brigham Young’s estate seem to have had little in common with other frontier children. Nowhere in Elliott West’s Growing Up With the Country: Childhood on the Far Western Frontier does one find anything resembling life as the child Zina experienced it. Where their contemporaries in less favored circumstances would have been essential to the work of the family farm, house and barn, field and pasture, Brigham Young’s daughters of the Lion House grew as young princesses whose main employment was to learn and to play. Clarissa Young, ten years younger than Zina, has left an account of a child’s life in the household, where, as she put it, “Life for us was one continual joy. There were so many of us to plan picnics in the hills, picking wild flowers, hunting pretty mossy places to play with our dolls, and build houses with sticks and stones, that the days never seemed long enough to do all the things we planned.” Only at fruit harvest does Clarissa remember long hours of picking strawberries for preserves, of paring and drying peaches. But even then it was only a day at a time, since each family would be assigned its turn in the “upper garden,” where the heavy work had all been done by employed gardeners. Susa Young, writing later about their lives as sisters told of Zina’s teaching them to “fashion clay dishes,” to make “whole armies of paper dolls with bright colored dresses,” telling stories of “blue-eyed, silver-tressed fairy queens and brown-eyed, curly-haired princes” to her wide-awake sisters on the sleeping porch.

From Zina’s own accounts comes the picture of herself and her sisters, especially the ten of them so near in age, putting on “theatres” in the yard or the barn; going to school to Karl G. Maeser, whose work they made difficult by defending one another against his discipline; taking lessons in dance and elocution; and finally acting for real in the Salt Lake Theatre.

From the time she was thirteen until her marriage at eighteen, Zina was a favorite there. Among her admirers was the intelligent and urbane T. B. H. Stenhouse, then editor of the Daily Telegraph and ardent and articulate defender of the faith, including plural marriage. In his first wife Fanny’s account, we are told that her husband pursued the young actress, and for fifteen months they courted, until the day was fixed, the wedding dress made. For whatever reason, her father’s growing suspicion of Stenhouse’s involvement with the schismatic Godbeite faction, or her own intuition, Zina broke off the engagement, and married instead the staid and secure Thomas Williams.

The bare facts of their life together have been noted above; what happened shortly after his death is less well known. For a time the young widow stayed on with her mother in the little house on Third South and State streets, consoled by their neighbor Emmeline B. Wells. Her father, however, concerned over the boys’ future, sent Zina to join her brother Chariton in Sevier County, where she could take up a homestead preemption of a quarter section. “Proving up” required that she build a house and other improvements and stay a year. George Washington Bean, a leader in the United Order enterprise there, noted in his account that his own wife Elizabeth refused to join him in the remote spot where Monroe and Glen wood now stand; that Zina lasted as long as she did does her credit.

The winter was more than she could take, however. Family memory tells of the one dark night when the wind blew so fiercely through the chinks in the log cabin that no candle would stay lit, and the young widow was left with only her three- and six-year-old boys for comfort through the long dark hours. One is not surprised that by spring Zina’s letter to her mother was written from Chariton’s house, where she spent her remaining time. The image remains; this experience was not a frivolous adventure, but an ordeal about which Zina herself seldom spoke, a “dark night of the soul,” as it were. The documents are silent as to what she learned from it.

That was 1877, and Brigham Young and entourage, including Zina Diantha, would be travelling to St. George for the dedication of the now finished temple. Zina and the boys, it was arranged, should come too, and be sealed by proxy to their deceased husband and father. Back in the world of the Young establishment, Zina could not, would not, return to the life of a pioneer, at least not in Sevier County; she arranged for a school to teach in the north, and then found herself, at her sister Susa’s suggestion, back under the tutelage of their schoolmaster Maeser at the struggling Brigham Young Academy. Once again Zina found herself valued: while her mother kept her boys, she was again a schoolgirl, praised by Maeser, courted by several young hopefuls, and finally assigned with Emmeline B. Wells to represent Mormon women at the national women’s congress in Washington.

Zina’s diary of that venture reveals a young girl, alternately frightened and flirtatious, travelling by train the distance her mother had walked. Arriving in Washington, D.C., she faced the challenge of considering herself a woman among women; of conversing with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton; of calling on senators Thurman and Hoar, and attorney general Devins (“a crusty old man; we gave him some pretty strong evidence”); of speaking up for her people before her sisters, and feeling herself on display: “Dear me,” she wrote in her diary of the congress, “what an awful thing to be an Elephant. The ladies all look at me so queer.” And finally, after several tries, bearding in his den the fearsome Senator Edmunds, he who sponsored two successive bills aimed against the practice of polygamy. “We gave him a strong testimony and told him he was [crossing] arms with the almighty. . . . He gave no particular encouragement.

Zina returned from Washington a woman grown, ready to take her place as a professional person. It was after that that she met and married Charles Ora Card and, with him, took leadership of a Mormon colony in a new land. No longer was she frightened by lonely nights with fierce winds blowing, nor stymied in conversation with the great ones, the occasional English nobility who came to call. The little princess had become a queen.

Zina had also dipped her toe into the mainstream of American womanhood; many of her Mormon sisters would follow, until, still in her lifetime, they would take their place in the larger sisterhood. The Americanization of Utah meant not only the political compromises necessary for statehood, but overwhelming shifts in lifestyle for individual Latter-day Saint women. Zina Diantha had come to Utah to escape the gentile world; walled in by the friendly Wasatch, she sought for union among the Saints, liberty to practice their religion, safety for her chicks in a nest of her own feathering. That she was the first of Brigham’s wives to travel south in protest against Johnston’s army, and the last to return bespeaks her determination. Zina Card, having suffered under the threat of gentile enforcement, was learning another defense: she would go in among the “enemy,” and win them over to friendship. Her move into Canada differs from her mother’s into Utah in that she was coming, not among usually peaceful native Americans, although there were those, too, and she learned to care for them, but among gentiles who were there first. The newspapers of Lethbridge and Fort Macleod are dotted with notices of her comings and goings among the residents there. That the first Lees Creek celebration of Dominion Day-Fourth of July holidays was so well attended by local ranchers, Blood Indians, and the RCMP served well to placate suspicious neighbors, and Zina’s later salons, where invited guests from Lethbridge performed, kept feelings amicable. There were no protective mountains between Mormon Cardston and gentile Lethbridge, and the Card leadership made sure there was no need for them.

In this milieu of homegrown culture and hard-sought education, Canadian-born Zina Card (Brown) grew up, a prairie waif with aristocratic possibilities. Born in the homey “Canton flannel palace,” a log cabin of her mother’s improving, she was a favorite of the townsfolk, the visitors, and the Indians, one of whom once brought a papoose as a gift for the ten-year old Zina. Her childhood, less privileged than her mother’s, was nevertheless enriched with cultural activities. If she could not act in the Salt Lake Theatre, she certainly could in the frequent offerings of the Cardston Dramatic Society; and if she never heard concerts in the Tabernacle, she did participate with the young folk in song fests to her mother’s accompaniment on the reed organ in the parlor.

The move to Logan when Zina was fifteen was fortuitous for the very active young girl. Her correspondence with her later-to-be husband Hugh Brown reveals a young coed eager about her possibilities. As a student at Brigham Young College, she asks his advice: should she “take up elocution entirely after this coming year of school or qualify as a Domestic Science teacher?” Hugh encourages her in either, adding, “I know you will make a success of whatever you undertake.” Following Hugh’s mission and his return to Cardston, he proposed marriage to Zina. Her reply begs time to consider, that “I am going to college this year and would like to go a number of years more … to carry out my plans that I have cherished so long.” One of those plans was to spend eight months in New York studying elocution, a serious endeavor at that time. Hugh respected that decision, though it is for him a “rebuff that turns earths smoothness rough.” Zina recants, and announces that she will instead attend the University of Utah, under Maude May Babcock. Hugh, for his part, has been “called” to enlist in the Canadian army, to “keep our friends in the East from saying the Mormons are disloyal.” The two careers seem bound in contrary directions. Hugh came to Utah at April general conference time, 1908. No correspondence is left to detail their meeting, but his journal states succinctly “I became engaged to Miss Zina Y. Card who promised to become my wife in June.” There was no question as to whose career would continue, whose be given up; they moved to the Alberta prairie town immediately following their wedding on 17 June 1908, and Zina became full-time wife and mother, a role she would continue throughout her life.

This fourth Zina was as much of her era as were her foremothers of theirs. Writing a Mormon position piece in 1926, Zina’s sister Susa and daughter Leah defended the kind of choice Zina had made, to forsake the university and a career. Counting as appropriate the division of spheres, they wrote: “Yet her creative home labor ranks side by side, in earthly and heavenly importance” with her husband’s. “His in the marketplace—hers at the hearthstone. He is the leader and she follows, not because she must, but because she will. She chooses her sphere as he chooses his.” This first generation of twentieth-century women counted themselves lucky to be well supported in their homes; the Victorian separation of spheres by gender seemed to them appropriate, and to maintain a marriage well worth whatever sacrifices it required. Zina Brown’s whole being, from the time of her marriage to her death found its meaning in her “Dear Hugh” and their children. Following her stroke, her daughter reported, her husband became her remaining link with meaning: she “wilted like a flower” when he was gone on church assignments.

Four Zinas, then. Four “representative women” of Mormondom. Four generations during which the church of the restoration moved through stages of charisma, canonization, and developing orthodoxy, and the culture developed through radical separatism, then defensive activism, to accommodation and diehard conservatism. Century by century, generation by generation, they responded to the world as they found it, to the church as it presented itself, and in their responses created their lives.

We twentieth-century observers of their lives see them through a glass grown dark with time’s passage. Prone to assume that our natures are the same as theirs, that contemporary Mormonism is as it always was, we judge their behavior by our lights, and are baffled by what we see as irrational, inauthentic, even bizarre behavior. Zina Baker’s insecurity in her sense of her own salvation, her determination to experience her own and William’s depravity before they can claim the gift of grace, seem strange prefaces to conversion. Zina Diantha’s use of the gifts of the spirit—prophecy, tongues, blessing, healing—would embarrass most of us were they to reappear. Zina Card’s confident leadership, and that of her sisters, in running their own programs with or without priesthood leadership would create a threat in a contemporary stake. And even Zina Brown’s subordination of her own identity under that of her husband is called into question by a generation of career-bound Mormon women facing the expectation of necessary wage earning.

Enter the historian. He, she, I, did not create the dissonance to which we respond here. The historical reality exists independent of our knowledge or ignorance. The scholar’s task is to recreate the milieu in which the people of the past lived out their lives, to see the events of the past through the eyes of those who experienced it. To scorn Zina Baker’s Calvinist Presbyterianism is to disavow the way which led her to a better way; to criticise Zina Diantha for her obedience to Joseph Smith’s request is to place our existential premium on private authenticity over her divinely confirmed faith that God speaks through prophets. To fault Zina Card for being a queen bee in a democratic Mormon community is to ignore the respect ability and with it the goodwill of the surrounding gentiles, which she won for her coreligionists. And to accuse Zina Brown of selling out her gender’s right to individual identity is to demean the familial roles she chose, and having chosen, fulfilled supremely well.

But to understand, to value, and to apply to our experience our knowledge of these people of the past we must see them in their own world, as they saw it, know the limits of their possibilities as they knew them, assess their achievements according to their own purposes.

Each in her own time, each of the first four Zinas, and, I suspect, the two who followed, has played out her life as seemed her best. God grant we all may be so true, and so blessed.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue