Articles/Essays – Volume 05, No. 4

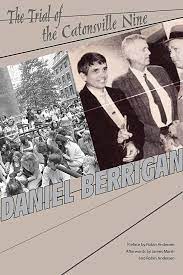

Dramatic Christianity | Daniel Berrigan, The Trial of the Catonsville Nine

I begin these notes on 9 April 1970. Two hours ago, at 8:30 a.m.,

I became a fugitive from injustice, having disobeyed

a federal court order to begin

a three-year sentence for destruction of draft files two years ago.

It is the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

in Flossenburg prison, for resistance to Hitler.

Thus begins Father Daniel Berrigan’s poem, “The Passion of Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” which in some ways is also a poem about his own passion. On 17 May 1968, prompted by conscience and a courage similar to that of Bonhoeffer, Daniel and Phillip Berrigan, Jesuit priests, went with seven of their friends into draft board number 33 at Catonsville, Maryland, where they confiscated 378 individual draft files. They carried the files to an adjoining parking lot, poured homemade napalm on them and burned them. They did this, they said, only after painful and thoughtful deliberation and prayer. And they did it in broad daylight fully aware of the con sequences; as Father Berrigan said, “Wide awake, neither insane nor amnesiac.” As a result of this symbolic protest against the war in Southeast Asia, the nine were arrested, tried, and found guilty of destroying government property.

While awaiting sentence for the action at Catonsville, Daniel Berrigan wrote a play dealing with this civil (and, as he would say, divine) disobedience. The Los Angeles Center Theatre Group’s “New Theatre for Now” staged the play last August.

This first production of The Trial of the Catonsville Nine was a unique theatrical experience. Those of us who attended the play were well aware that Father Berrigan had chosen to go underground rather than go to prison and had been at large since the preceding April, but we were hardly prepared for the tape recorded message which he sent to the audience from his hiding place or the special letter from him enclosed in the program. FBI agents were tapping Center Theatre Group telephones and undercover agents were in the audience. One had the feeling of not merely seeing a play but of being a participant in significant and current events. One also had the feeling that it was to be a unique dramatic experience, and indeed it was, even though as a play and as a dramatic production it fell short of great theatre.

Perhaps it was the subject matter that made the play unique: in a theatrical world given essentially to the exploration of surd and absurd and the presentation of nakedness and negativism, here was a play that was blatantly Christian, one that dealt with what Faulkner called the “eternal verities”: love and courage and sacrifice and integrity.

What the play tries to do essentially is to give the reasons why these nine Christians went to Catonsville. In the third scene, “The Day of the Nine Defendants,” each of the nine outlines his or her reasons for engaging in civil disobedience.

David Darst, who called the adventure “a Bonnie and Clyde act/on behalf of God and Man” traced the beginnings of his action to his exper iences in the ghetto:

I was living last year

in a poor ghetto district

I saw many little children

who did not have enough to eat

this is an astonishing thing

that our country

cannot command the energy

to give bread and milk

to children

Yet it can rain fire and death

on people ten thousand miles away

for reasons that are unclear

to thoughtful men

When asked by the prosecution if his religious belief had anything to do with his actions at Catonsville, Darst replied,

Well I suppose my thinking

is part of an ethic

found in the New Testament

You could say

Jesus too was guilty

of assault and battery

when he cast the money changers

out of the temple

and wasted their property and wealth

He was saying

It is wrong to do what you are doing

And this was our point

we came to realize

draft files are death’s own cry

we have not been able

to let sacred life

and total death

live together quietly within us

Thomas Lewis, who along with Phillip Berrigan was awaiting a six year prison sentence for burning draft files in Baltimore at the time he went to Catonsville, says,

I came to the conclusion

that the war

is totally outrageous

from the Christian point of view

He adds,

The spirit of the New Testament deals

with a man’s response to other men

and with a law that overrides

all laws the one law

is the primary law of love and justice

toward other men

The movement toward Catonsville for Thomas and Marjorie Melville (an ex-priest and ex-nun who later married) started among the poor in Guatemala where they were working as Catholic missionaries. Of their experience there, Thomas Melville says,

I hesitate to use the word “poverty”

they were living in utter misery

so I thought perhaps instead of talking

about the life to come

and justice beyond

perhaps I could do a little

to ameliorate their conditions

on this earth

and at the same time

could give a demonstration

of what Christianity is all about

For trying to organize the poor and help them in their struggle against the Catholic Church, the United Fruit Company and the Government, the Melvilles were expelled from Guatemala.

So with each of the others: Mary Moylan (who at this writing is still a fugitive from justice—or injustice as Daniel Berrigan would say), who witnessed American planes piloted by Cubans dropping bombs on the people of Uganda; George Mische who saw “two democratically elected governments [in the Caribbean] . . . overthrown by the military/with Pentagon support”; John Hogan; and the two Berrigan brothers, both of whom it seems had been moving toward Catonsville all their lives.

Nine Christians, lead “slowly and painfully” by their consciences to act against a war they felt to be immoral. Nine human beings believing that what they did might somehow make a difference. As the lawyer for the defense states in the play, “They were trying to make an outcry, an anguished outcry, to reach the American community before it was too late. It was a cry that conceivably could have been made in Germany in 1931 and 1932. It was a cry of despair and anguish and hope, all at the same time. And to make this outcry, they were willing to risk years of their lives.”

I wondered as I saw the play as I have wondered many times since in considering the implications of Catonsville how other Christians and especially how other Mormons would regard such acts of conscience. My guess is that most would consider these acts misdirected at best and criminal at worst. They might say what some of Thoreau’s neighbors said about John Brown, “He threw his life away.” And Daniel Berrigan might be tempted to say what Thoreau said in response, “Pray, which way have they thrown their lives?”

It is interesting to contemplate why so many of us would be unsympathetic to such acts. There are those who would understand, however: Thoreau, who went to jail rather than pay his taxes to a government which supported slavery, would understand; and Gandhi and Martin Luther King would understand; Joseph Smith, who spent many days and nights hiding from his would-be captors, would understand, as would hundreds of polygamists who eluded Federal marshalls on the underground railroad and went to prison when they were unsuccessful; Lot Smith and his brethren who committed acts of civil disobedience against Johnson’s Army would understand. Why wouldn’t we?

Having seen Daniel Berrigan’s play and having followed somewhat the course of events following from Catonsville, I was sorry to read in the morning paper several weeks after the play that he had been captured by FBI agents at the home of a friend. He is now in prison serving his sentence, but imprisonment has not stopped the force of his personality or the power of his writing. Recently he and his brother were accused by J. Edgar Hoover of being the force behind the East Coast Conspiracy to Save Lives. Perhaps the circle from Catonsville has begun to enlarge; perhaps others have taken courage from those nine Christians, faith from their faith.

A revised and improved version of The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, staged by the famous Phoenix Theatre, has been playing at the Good Shep herd Church in New York. It will return to the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles on June 17th.

While it is unlikely that this modern morality play will take a place in our dramatic literature alongside Death of a Salesman, and Long Day’s Journey Into the Night, its message, were we to take it seriously, might help us begin as individuals and as a people that long night’s journey into day which we must take before we and our good earth can truly be renewed.

The Trial of the Catonsville Nine. By Daniel Berrigan. Boston: Beacon Press, 1970, 123pp. $1.95. Staged by the Center Theatre Group’s New Theatre for Now at the Mark Taper Forum, Los Angeles, August 1970.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue