Articles/Essays – Volume 50, No. 1

Do We Have to Believe That? Canon and Extra-Canonical Sources of LDS Belief

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

For two days in October 2010, “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” was part of the LDS canon. Maybe.

In his October general conference address, “Cleansing the Inner Vessel,” Elder Boyd K. Packer referred to the Proclamation as divinely inspired revelation. “It fits the definition of a revelation” he stated, and “members of the Church would do well to read and to follow.”Elder Packer did not specify which “definition of revelation” he was considering.He might have meant that the Proclamation was revelation because it was signed by revelators.Alternatively, he might have meant that it was revelation because it was delivered by a prophet at a general conference of the Church, albeit in an auxiliary session that was not then officially considered part of conference. Nevertheless, the claim was sufficiently problematic that within seventy-two hours it had been changed on the Church website, and it was later published in the Ensign to read, the Proclamation “is a guide that members of the Church would do well to read and to follow.” Church Public Affairs spokesman Scott Trotter issued a statement suggesting that Elder Packer made the changes himself, but he stopped short of suggesting that Elder Packer recognized the need for the change on his own.

This incident highlights the complicated and sometimes contested nature of LDS scripture. With its acceptance of additional canonical books—the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price—as well as its belief in modern prophets, seers, and revelators, Mormonism’s canon is open and mutable. New revelation can be added to the canon when received by prophets, presented to the Church membership, and accepted by common consent of the Church’s general assembly. However, “scripture” is not understood to be only that which is contained within the pages of the standard works. The Doctrine and Covenants allows that “whatsoever [Church elders] shall speak when moved upon by the Holy Ghost shall be scripture, shall be the will of the Lord, shall be the mind of the Lord, shall be the word of the Lord, shall be the voice of the Lord, and the power of God unto salvation” (D&C 68:4). Thus, Church members grant considerable authority to the words of Church leaders, which creates a sort of extra-canonical scripture. Despite the oft-repeated claim that pronouncements from the general conference pulpit are not infallible,conference talks have profound influence on Mormon culture and day-to-day religious experience. And in a culture of increasing authoritarianism, the status of Church leaders’ words is ever rising.

This essay will attempt to clarify the process by which extra-canonical texts gain the status of “scripture” in contemporary Mormonism. First, I examine the meaning of “formative” and “normative” scripture. Second, I examine in detail the use of scripture in general conference addresses. Third, I examine institutional efforts to teach scripture to LDS youth, with particular emphasis on the scripture mastery program. Finally, I examine the status of “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” which generated the dominant doctrinal theme of the last two decades, as well as the more recent gay exclusion policy. Ultimately, the nature of what constitutes scripture for Latter-day Saints resists facile explication, but I hope this discussion will bring into sharper focus the chaos out of which “Mormon scripture” emerges.

Formative and Normative Scripture

In the context of world religion, scripture has been defined as any text that is seen within a religious community as speaking authoritatively about things transcendent.It is incumbent upon believers to learn what scripture says and live by its precepts. However, core beliefs often come from extra-canonical literature. Jewish scholar Moshe Halbertal distinguishes between what he calls normative and formative scripture.Formative scripture are texts that give a religion its cultural heft: they transmit the stories, histories, and vocabulary that form the common heritage of the believers. Normative scripture are those writings that describe the rituals, practices, and commandments that are binding on believers as members of that faith community. Halbertal regards the Torah as normative—providing Judaism’s laws, rituals, and tradi tions—and the Midrash as formative—providing its culture and heritage. However, several scholars have pointed out that the situation is actu ally reversed. Every Jewish child knows the formative stories of Noah and Daniel, but a Hassid who wants to know norms—like what kind of materials are permissible in a kosher cooking pot, or the maximum number of steps one is allowed to take on the Sabbath—turns not to the Tanakh but to the Midrash or Halakhah.

In Mormonism, we have the same dynamic with the standard works and general conference addresses. There is, with the aforementioned exception of the Proclamation on the Family, no doubt about what is and what is not part of the canon. However, conference addresses have a non-binding-but-official exegetical function for the culture. Halbertal would call our canon normative and the stories and interpretations of general conference formative; however, just as in Judaism, the two are often reversed in practice. For example, clear normative prohibitions against tattoos, piercings, and even consumption of alcohol and coffee come not from canonized scripture, but from interpretations of scripture presented in conference addresses.In contrast, formative elements from general conference such as the iconic phrases “tender mercies” and “the work and the glory” are actually quotations from scripture.

Arguing that general conference functions as scripture is startling and distasteful to many progressive Mormons. Nevertheless, one need only reflect on the radically different ways Jewish and Christian churches approach the first five books of the Bible to see that extra-canonical influence is often stronger than the canon itself. Indeed, Benjamin Sommer argues that “one can rightly say that the books in question are not the same books at all but entirely different works that happen to have the same words.”(This is particularly true in Mormonism, where the words of the Pentateuch are not the same as those in other faith traditions, thanks to the Joseph Smith Translation, and the books of Abraham and Moses in the Pearl of Great Price.) Generally, “lived scripture” derives from emphasizing some parts of the scriptural text and ignoring others. Steve Epperson has suggested that such shaping of canon is unavoidable: “Every scripture, every law, prohibition, and narrative cannot be equally authoritative. There’s a ‘canon within the canon.’”General conference addresses, therefore, can be described as “normative scripture,” a sort of meta-scriptural Mormon Midrash that shapes the way we read the canon itself.

Shaping the Canon

Like the Jewish Midrashim, normative conference talks derive their authority from the formative scripture they interpret, and in the process shape how Mormon culture reads scripture. General Authorities emphasize some scriptural passages, ignore others, and, in some cases, tear them out of the original context. This misappropriation of the original text is generally done so subtly and/or repeatedly that it becomes more authoritative than the text itself. However, at least in an LDS context, outright doctrinal innovation would theoretically be permissible only in the form of a new revelation, presented by a prophet (D&C 43:3) and by a sustaining vote of the church body.As a result, general conference speakers are generally reluctant to stray too far from scriptural texts, even as they unwittingly bring their own preconceptions and understanding to bear upon them. Elder Boyd K. Packer once remarked that his goal as a speaker and teacher was “to say nothing that has not been said before,”yet he is arguably among the most influential of the twenty-first century apostles. If we accept this statement at face value, Elder Packer was unaware of his own role as a shaper of doctrine and practice. This sort of ironic contradiction is only possible in situations where robust theology is actively discouraged. Margaret Toscano explains, “various Mormon hermeneutics have emerged because people use scripture in different ways in different contexts. Nevertheless, we do not have avenues for understanding and discussing what we are doing in interpretation.”In fact, the word “hermeneutics” occurs only twice on the official LDS.org web domain, and both times in the context of disparaging secular scholarship.

Perhaps the most obvious way our culture constructs its “scripture” is by continually repeating some verses and altogether ignoring the rest. This method can be examined analytically by mining the text of general conference addresses. In the analyses below, I use citations from talks delivered between 1974 and 2016, because 1974 forms a useful lower limit on institutional memory as the earliest talks available on LDS.org.

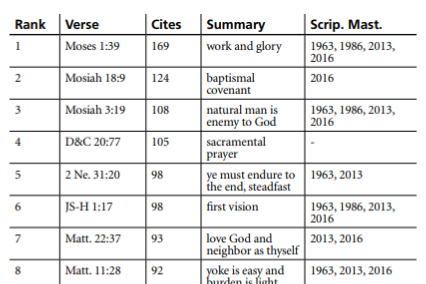

The most cited verses during this time period reflect a commitment to what almost all members would regard as the key components of LDS theology (see table 1). The most cited scripture is Moses 1:39 where God reveals the purpose of creation: “to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.” The second most cited scripture is Mosiah 18:9, which can be thought of as the purpose of the LDS Church: Alma the Elder founds his church by the Waters of Mormon,telling his congregants they will be obligated to “mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort.” Many verses in the top ten emphasize the importance of cultivating loving interpersonal relationships and providing service (e.g., Mosiah 18:9, Matthew 22:39, Matthew 25:40), and the peace to be found by loving and serving Heavenly Father (e.g., Mosiah 3:19, Matthew 22:37, Matthew 11:28, 2 Nephi 31:20, D&C 20:77).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1: The most cited scriptures, 1974–2016, see PDF below, pp. 87–88]

The “scriptural vocabulary” of conference speakers is extremely broad (see figure 1). The Gini-Simpson measure of diversity never dropped below 0.995 in any conference session; i.e., 0.5% of citations were to verses of scripture cited elsewhere in the conference session. It might be expected that the widespread use of digital scriptures beginning in the twenty-first century would tend to increase the diversity of scriptures by facilitating the ease with which speakers could find obscure passages. This appears to not be the case; any trend through time is mathematically insignificant and equivocal.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1: Sciptural Diversity per Session, see PDF below, p. 89]

This implies that scriptural emphasis is actually quite diffuse, which begs the question, are the top verses in table 1 surprisingly common? To answer this question, we need some idea of what the “expected” distribution of scriptural citations would be. A great many linguistic phenomena obey Zipf ’s law, which states that as the rank of a datum increases, its value decreases by a factor of 1/rank.For example, in a large corpus of English text, the most common word (“the”) occurs roughly twice as often as the second most common word (“of ”), and three times as often as the third most common word (“and”), and so forth.This relationship holds for not only written English, but also Latin and Chinese,spoken American English,and two- and three-word phrases,but interestingly does not apply to random or computer-generated text.In other words, it is a startlingly powerful null model for data of this kind.

Yet scriptural citations in general conference do not conform to Zipf ’s law (see figure 2). The most-frequently used verses receive far fewer citations than we would expect if scriptures were used like words and phrases.This suggests that there is a conscious tendency among speakers to avoid repetition of the same verses, which may be explained as an attempt to reduce audience boredom, to establish the bona fides of the speaker as one familiar with the even the obscure passages of scripture, or to avoid promulgating an “official” interpretation of a passage through focused consideration. [Figure 2 available on next page.]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 2: Zipf plot, see PDF below, p. 92]

The number of verses cited per conference has been drifting generally upward, with April 2013 representing a peak of just over 1,100 verses, a value expected only once every two centuries based on the previous seventy-eight conferences (see figure 3). This general trend may represent a relaxation in the “defensiveness” of speakers, who feel that the canonical text and their personal beliefs align so closely that no explanation of the text is needed. Alternatively, this may represent an increasing reliance on the authority of scripture to support points in the talk. In any case, the trend is fairly weak; this peak was followed in April 2014 by the lowest verse count (353) of the time period, compromising the strength of the relationship. While still significant (p=.026), approximately 95 percent of the variability in the number of citations per conference session cannot be explained by a simple increase through time.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 3: Verses Cited per Session, see PDF below, p. 93]

The books of the scriptures, indeed the standard works themselves, receive very different amounts of attention (see figures 4 and 5). By any measure, the Old Testament receives far fewer citations than the other standard works. This is somewhat in conflict with divine instruction. For example, in the Book of Mormon Jesus asks the Nephites to “search the words of Isaiah” (3 Nephi 20:11) and later affirms that “great are the words of Isaiah” (3 Nephi 23:1). Despite these injunctions, verses of Isaiah comprise an insignificantly small fraction of the scriptural references in general conference talks, especially for a book of such length. Since 1974, it has been cited 737 times; for a book with sixty-six chapters, one would expect 2,260 citations (p=1e-319); for 1,292 verses and 150,958 characters, 1,666 citations (p=7e-152) and 1,664 citations (p=2e-151) respectively. Yet Isaiah is relatively citation-dense relative to the rest of the Old Testament. Only the short book of Malachi receives more citations per pagethan the Book of Mormon, and all receive fewer than the New Testament, Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. Perhaps this shift in attention away from the Old Testament can most clearly be seen in the fifteen citations per page received by Genesis, in contrast to the forty per page of Abraham and fifty-three per page of Moses, books of purportedly overlapping material.

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 4 and 5, see PDF below, pp. 95–96]

Ignoring the Old Testament is even clearer when considering the fraction of verses that have been cited at least once, as opposed to the total number of citations (figure 6). Only Genesis and the short books of Daniel and Malachi have had 20 percent of their verses referred to by general conference speakers. By contrast, not a single book in any other standard work falls below this cutoff value. Lamentations remains the only book never cited by any speaker during the time period. [Figure 6 available on next page.]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 6, see PDF below, p. 98]

Some of the change in attention has been influenced by prophetic mandate. In 1985, Ezra Taft Benson challenged the Church to spend more time and effort reading and studying the Book of Mormon, and emphasized its centrality many times thereafter.The fraction of citations that referenced the Book of Mormon had been holding steady at approximately 15 percent, but after 1985 increased rapidly to ~30 percent, and has remained at, or slightly above, that level ever since (figure 7). The difference between the pre-Benson citation rate and that thereafter is highly significant (t=11.4, p<.0001). Despite this increase, the number of citations per Book of Mormon page remains approximately half that of the New Testament, Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. Indeed, Benson himself supported his refocusing on the Book of Mormon mostly with references to the Old Testament and Doctrine and Covenants. Across his career, Benson’s general conference speeches show roughly twice the citation density to the Doctrine and Covenants as to the Book of Mormon. [Figure 7 available on next page.]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 7, see PDF below, p. 100]

Distinct Voices: Variability among Speakers

Speakers exhibit a wide variety of styles in their use of scripture. Elder Russell M. Nelson quotes scripture more often than other conference speakers, citing 5,499 verses in general conference, outpacing second place Elder Neal A. Maxwell at 2,969 by 85 percent (table 2). Even adjusting for the amount of Conference material delivered, Nelson remains atop the leaderboard for the number of references per page of text among apostles (see table 3) due to his tendency to paraphrase a scriptural story, but to cite the entire section of scripture in his footnotes. In a different mode, Elder Maxwell’s rhetorical style involved weaving together numerous quotations from scripture and other sources in a sort of word-collage that was beautiful, erudite, and occasionally opaque in meaning.

[Editor’s Note: For Tables 2 and 3, see PDF below, pp. 101–103]

Apostles generally cite scriptures more often than other speakers, though not significantly more (5.4 per page versus 4.3 per page). It is remarkable that the five prophets during this study’s period had low citation densities. Ignoring newcomers Elders Rasband and Stevenson,President Hinckley has the lowest citation density of all apostles, President Monson is fifth lowest, President Kimball is seventh, and President Hunter is thirteenth; President Benson, at nineteenth, is the only prophet with a citation density above the apostolic, or the global, average. The rankings are even lower when based on verses per talk, because prophets typically deliver a very short, and hence scripture-poor, introduction and farewell at each conference. As the ultimate earthly authority for Latter-day Saints, prophets may feel more liberty to depart from canonical sources when interpreting the gospel and establishing policy for the Church.

Women and Scripture

There have been times in history when women were not only forbidden to read from scripture in public meetings, but not even permitted to read scripture in the privacy of their own homes. First-century AD Rabbi Eliezer taught that “If any man gives his daughter a knowledge of the law [Torah], it is as though he taught her lechery.”The apostle Paul, in a hotly contested passage, supports such silencing, at least if we take his words at face value:

The women should keep silence in the churches. For they are not per mitted to speak, but should be subordinate, as even the law says. If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church. (1 Cor. 14:34–35)

Later, in 1 Timothy 2:12, he wrote “I permit no woman to teach or have authority over a man; she is to keep silent.”Nevertheless, based on these passages some neo-Calvinist and Baptist churches today still do not allow women to give sermons or even read scriptures in public.

Given this pattern of silencing women, I find it somewhat chilling that women conference speakers appear to self-repress their use of scripture, citing fewer than half the number of scriptures men do (5.00 per page versus 2.38 per page, p<.0001; 16.8 per talk vs. 8.1 per talk, p<.0001). This reluctance to use scripture is even more problematic given the under-representation of women in general conference addresses generally (figure 8). Of the sixty-four female speakers, only Barbara Thompson has a citation density higher than that of the average man’s, and she is also the only female in the top fifty among all speakers who have delivered at least three talks (at #39).Even correcting for the small number of women participating in general conference, the probability that so few women would be represented in the top fifty is less than 1 in 10,000 (91 hits in 1,000,000 bootstrap resamplings) if the citation rate were distributed randomly.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 8, see PDF below, p. 106]

Learning Scripture and Memorization

Official discourse frequently encourages Church members to read the scriptures daily and for adults to teach them to their children. Since 1980, Gospel Doctrine manuals for Sunday School classes have been structured to focus on one standard work every year.However, the sorts of things Mormons are supposed to learn about scripture are fairly rigidly prescribed.

During the study period there were frequent challenges issued to Church membership to read the entire Book of Mormon in a year or some part of the year, but General Authorities issued no such challenge to read the other standard works even though they cited the New Testament at a much higher rate. It could be argued that this is an attempt to channel the developing relationship with deity into an exclusively Mormon context.

General conference speakers typically urge members to study the scriptures in rather vague and unambitious ways. President Spencer W. Kimball declared enthusiastically if rather unspecifically, “We want our homes to be blessed with sister scriptorians—whether you are single or married, young or old, widowed or living in a family . . . . Become scholars of the scriptures!”In 1959, then-Elder Hinckley suggested that children should memorize references to scriptures, but not necessarily the verses themselves: “May I suggest that in our family night gatherings we make it a project to memorize one scripture citation a week pertinent to this work. At the conclusion of a year our children will have on their lips a fund of scripture which will remain with them throughout their lives.”More recently, Elder Richard G. Scott “suggest[ed] that you memorize scriptures that touch your heart and fill your soul with understanding. When scriptures are used as the Lord has caused them to be recorded, they have intrinsic power that is not communicated when paraphrased.”Even more narrowly, Elder L. Tom Perry argued, “What a great blessing it would be if every member of the Church memorized the Articles of Faith and became knowledgeable about the principles contained in each. We would be better prepared to share the gospel with others.”

Given their complex history, silence on some key doctrinal topics, and extensive descriptions of other de-emphasized beliefs, memorizing the Articles of Faith seems like a rather low bar to clear in order to qualify as an informed proselytizer.Nevertheless, they are usually the only scripture verses that children are expected and actively encouraged to memorize in Primary. They have been set to music in the English Children’s Songbook (though no other languages officially), and being able to recite them is required for several Primary and youth awards. This project of memorization has apparently had an effect as these children grow up to become the leadership. The Articles of Faith have the highest per verse and per character citation rate of any book in the standard works, and it is the only standard work whose every verse has been cited at least once. They are one of only five of the 1,422 chapters with ten or more verses in the standard works for which every verse has been cited at least three times. Clearly, there is a correlation between the verses children memorize and the verses General Authorities cite.

The Articles of Faith also provide a microcosmic view of global trends toward mainstream culture and authoritarianism noted by numerous other scholars. The tenth article of faith, which implies that Mormons will all relocate to the Midwest when Jesus builds his capital in Missouri, has been cited only eight times, and the gap between citations is increasing. Elder Cook cited this verse in October 2013 with the qualification that the gathering should be thought of as a metaphor, and, statistically the next reference to this verse would not be expected until April 2025. By contrast, the thirteenth article of faith, with its vague but palatable endorsement of moral qualities and good works, has been cited fifty-seven times. The authoritarian fifth article of faith (“a man must be called of God by . . . those who are in authority”) receives the second most citations, while the anti-hierarchical gifts of the spirit enumerated in the seventh article of faith are the least cited of all with just three references.

Scripture Mastery

The most visible form of scriptural memorization is the scripture mastery program for teenage LDS seminary students. The program began when a seminary teacher created a list of 160 significant scriptures in 1963, and it was implemented Church-wide by the early 1970s.The list was reduced to 100 in 1986, then changed again in 2013, according to a Church spokesman, to “align the references to the basic doctrines.”These nine basic doctrines had recently been defined for the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Sunday School programs as:

The Godhead

Plan of Salvation

Atonement of Jesus Christ

Dispensation, Apostasy, and Restoration

Prophets and Revelation

Priesthood and Priesthood Keys

Ordinances and Covenants

Marriage and Family

Commandments

The program was rebranded as Doctrinal Mastery in 2016, a tenth goal (“acquire spiritual knowledge”) was added, and the list of scriptures was again changed.

Analyzing the three changes can reveal interesting details about how scripture is being shaped by Church leaders. First, despite there being only 160 (in 1963) and 100 (on subsequent lists) “passages” on the official lists, most included more than one verse, for a total of 332 (in 1963), 203 (in 1985), 200 (in 2013), and 213 (in 2016) verses respectively. Of the 455 distinct verses used across the four time periods, 108 (24 percent) were retained on all four lists, while 214 (47 percent) appear on only one; both values are much higher than expected by chance (p<.0001). The first change in 1986 removed 158 verses, retained 174 verses, and added twenty-nine; the second change in 2013 removed sixty-eight verses, retained 135 verses, and added sixty-five (which included reinstating twelve from the original 1963 Scripture Chase list); and the most recent change in 2016 removed thirty-five verses, retained 165, and added forty-eight (seven of which appeared on the 1963 and/or 1986 lists).

Despite equal numbers of passages from each standard work, there are differences between them. The total number of unique verses is different across works (p=.0018), with nearly twice as many verses from the Doctrine and Covenants (141) as Book of Mormon (83) on the four lists, even though only 14.5 percent (n=12) of the Book of Mormon verses appear on all four lists. This is the lowest. The Old Testament has the highest retention rate (n=35, 30 percent), though the differences are not quite significant (p=.08), and neither is the rate of turnover (p=.17).

Is it true, as stated in the news releases regarding the 2013 reforms, that these substantial changes reflect a move toward more equal representation of the nine fundamental doctrines? To answer this question, I assigned every verse to one of the nine doctrines where at all possible, though I was unable to categorize fifty-six verses (table 4). Uncategorizable examples include “for the earth is full, there is enough and to spare” (D&C 104:17), “stupor of thought” (D&C 9:9), and “go and teach all nations” (Matt. 28:19). A fairly large number deal with proper treatment of other people (e.g., “inasmuch as ye have done it unto on of the least of these” [Matt. 25:40]), and another segment deals with scripture study (e.g., God’s word is “a lamp unto my feet” [Ps. 119:105]).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 4, see PDF below, p. 112]

In order to be even, there should have been thirty-seven, twenty-three, and twenty-two verses assigned to each of the nine doctrines on the first three lists, and twenty-one verses assigned to each of the ten categories on the 2016 list. If verses were assigned to categories randomly, we expect the final distribution of verses to categories to be off by an average of 4.5, 3.5, 3.5, and 3.4; furthermore, if the final distributions are off by more than 6.7, 5.3, 5.1, and 5.0 respectively, that constitutes statistical evidence the assignment was worse than blind. A human committee, non-randomly trying to distribute verses evenly, should be able to do substantially better than this. However, the actual observed deviations are very high: 25.4, 15.3, 14.1, and 12.2. Again, the average deviation for a list deliberately constructed with evenness as a goal should be lower than lists made randomly; instead, all four actual lists deviate from evenness so far that the probability of making such an uneven list randomly is less than one in a quadrillion.

Could it be that the lists are not evenly distributed because the original Scripture Chase list was so uneven that little improvement was possible given the number of changes on the new lists? The short answer, at least for the first three lists, is also “definitely no.” While it is true that each iteration of the scripture mastery lists moved closer to an even distribution, they did not move by very much. There is no statistical evidence that doctrinal distribution of verses changed at all on the first three lists (p=0.12). Given the suboptimal distribution of the original Scripture Chase list, by judiciously dropping 158 verses and adding twenty-nine (as actually happened), the 1986 list could have been only 5.1 verses from even. And given the actual 1986 list, dropping sixty-eight verses and adding sixty-five judiciously could have reduced the average deviation to 3.3 for the 2013 list. In fact, choosing categories at random for deletions and additions create more even distributions than observed 97.6 percent of the time for the 1986 reform, and 99.99 percent of the time for the 2013 reform.

The 2016 reform is another story. Of the forty-eight verses added, thirty-eight were added to categories underrepresented on the 2013 list, and nineteen of the thirty-five removed verses were from overrepresented categories. Only four verses on the list could not readily be assigned to one of the ten gospel topics, nor to the central gospel concept of community. While representation is still statistically different from even, there was clearly an attempt made to approach balance. It is almost as if the 2013 list was determined before the education goals were set, and the two were merely announced concurrently. Perhaps the aim of bringing the scripture list into accordance with goals is why the 2013 list was changed after just three years, compared to the twenty-three- and twenty-seven-year tenures of its predecessors.

Alternative Explanations for 2013 Reforms

If a move toward more equal representation of the nine fundamental doctrines was not behind the 2013 changes, what was? Direct involvement by the leadership is reportedly not the cause, as the suggestions of the Church Board of Education (which included Elders Nelson, Oaks, Ballard, and “members of the First Presidency”) resulted in only two changed references according to Chad Webb.President Thomas S. Monson’s involvement is particularly interesting, since out of the six leaders potentially involved in this decision, he has given the most talks and has a large number of citations to added scriptures (second only to Nelson), but had never cited forty-one of the sixty-five added verses in 2013, far more than one would expect by chance. By contrast, Elder Nelson and President Uchtdorf have both cited the added scriptures more than four times per year (though Elder Nelson has so many citations this is not by itself conclusive), a disproportionately large number of President Uchtdorf’s citations were to added verses, and a remarkably small number of verses were added that he hadn’t cited. Sisters Linda Burton and Bonnie Oscarson were also on the committee, but were very recent appointments and probably had minimal involvement. Curriculum director Thomas Valletta perhaps unwittingly revealed how much female involvement was supplied and/or valued when he praised the Board of Education as demonstrating that “the Lord is taking care of the seminaries and institutes through very well prepared and inspired men.”

Reading between the lines, as one often must in Church news releases, there appears to be more conflict between Church Educational System administration and Church leadership than the changes would suggest. Valletta refers to dozens of meetings over several months, cites input from auxiliaries and teachers, and admits that “not all of his favorites made the cut.” Similarly, Webb says, “There are a lot of wonderful verses, and you can’t put them all in there.” Even if we accept the claim that changes were not made directly by apostles on the Board of Education, it is still likely that changes were influenced indirectly by their importance to the leaders, as indicated by their use in general conference addresses.

It is, of course, very difficult to demonstrate what mechanism causes a pattern, since more than one process can result in the same pattern, and a failure to reject a hypothesis is not the same thing as confirmation. However, we can challenge the hypothesis that the Board of Education was influenced by the rate at which verses are cited in general conference by assuming it is true, and seeing if the logical consequences of such a statement are supported by data. Specifically, if the hypothesis is true, then:

1. The most cited verses in general conference should appear on the scripture mastery lists.

2. Conversely, verses on the scripture mastery lists should be often-cited in general conference.

3. The average number of citations per verse should increase from list to list.

4. Verses that have been added to the lists should be cited more frequently than those that have been dropped.

5. Verses appearing on all lists should have more citations than those appearing on only one.

1. Do the most-cited verses in general conference appear on the scripture mastery lists?

Because each standard work is limited to a constant number of passages on each list, comparisons are done separately for each of the standard works. In the Old Testament, of the twenty-seven verses cited twenty five or more times, eighteen of them appear on at least one scripture mastery list. However, all nine omissions are from Genesis, Moses, or Abraham, and may represent an attempt to avoid stacking all the passages into the first few weeks of the curriculum. The sixteen most frequently cited verses from the thirty-eight later books of the Old Testament are all included in scripture mastery. There may also have been some attempt to limit the length of passages memorized. For example, all six verses in Abraham 3:22–27 (the council in heaven) are among the most cited verses in general conference, but students are only required to memorize the first two.

Eight of the ten most-cited verses in the New Testament appear on the scripture mastery lists, including the top six. The two exceptions are John 14:27 (“Peace I leave with you,” sixty-four citations, #7), which was possibly omitted because two other verses from John 14 are already on the list, and John 3:16 (“God so loved the world,” sixty-three citations, #8), possibly omitted because of its association with evangelical churches.

Fourteen of the fifteen most-cited Book of Mormon verses appear on at least one scripture mastery list, eleven of them on the 2013 list. Alma’s baptismal covenant, Mosiah 18:9 (112 citations, #1 in the Book of Mormon and #2 overall), was inexplicably omitted until 2016. This is particularly perplexing considering how few verses fit the “ordinances” doctrinal category. Moroni 10:32 (“by his grace ye may be perfect in Christ,” seventy-five citations, #5) is also omitted, possibly because the cultural touchstone Moroni 10:4–5 (pray to have the Holy Ghost manifest the truth of the Book of Mormon, seventy-six and sixty-four citations, #4 and #10) is already in that chapter.

The Doctrine and Covenants scripture mastery lists include seven of the ten most cited verses. The editors omitted the sacrament prayer on the bread (D&C 20:77, eighty-three citations, #2) and Article of Faith 13 (fifty-seven citations, #9.5), probably because they are expected to be memorized elsewhere. Also, Joseph Smith’s plea to be full of charity and let virtue garnish thy thoughts (D&C 121:45, seventy-seven citations #3) has been left off all four lists, perhaps because nine other verses from that section have been included. The sentiment is echoed, perhaps deliberately, in the similar-but-obscure D&C 46:33 (“ye must practice virtue and holiness before me continually,” two citations, #1576), which was added in 2013, but removed in 2016.

Overall, the probability of ever being included on a scripture mastery list increases by approximately 1.15% for each general conference citation, a trend that is highly significant using both linear and logistic regression models (p<<.0001 for both).

2. Are verses on the scripture mastery lists often-cited in general conference?

The average scripture mastery verse has been cited 22.8 times in general conference, nearly five times more than the 4.6 citations the average verse from the pool of ~12,000 cited in general conference has received. Exceptions to this general rule are so rare as to be illuminating by themselves. There are a total of nineteen verses on at least one scripture mastery list that have never been cited; fifteen of these were only on the original 1963 list, and none were on the 2013 list. Curiously, the 2016 list reinstated D&C 130:23 (“A man may receive the Holy Ghost, and it may descend upon him and not tarry with him”), absent from the two previous lists, and added Ezekiel 12:16 (God speaks to Ezekiel after a fast of seven days). Both these verses reinforce the reality and difficulty of personal revelation; the next verse in Ezekiel, included despite just two general conference citations, establishes the hierarchical pattern of God teaching a prophet, who passes the teaching on to the people. Other seldom-cited scripture mastery verses have been used out-of-context to support LDS-specific doctrines, such as Ezekiel 37:15–17 (the stick of Joseph and Judah; one, eight, and seven citations); Jeremiah 1:4–5 (“Before I formed thee in the belly I knew thee”; three and fourteen citations); 1 Corinthians 15:42 (three degrees of glory; seven citations) and 2 Tim. 3:17 (scripture comes by revelation to prophets; seven citations). Most other exceptions are neighbors of high-citation verses, included to provide context.

The number of seldom-cited verses is not evenly spread across gospel topics (chi squared test p=.009). The fraction of verses cited fewer than ten times is high for prophets (65 percent), the restoration (47 percent), and family (36 percent), but low for the unofficial topics of community (5 percent) and study (8 percent).

3. Does the average number of citations per scripture mastery verse increase from list to list?

The mean number of citations increased significantly from the 1963 to the 1986 list (21.3 and 28.1, p=.0004), but did not significantly change on the two subsequent lists (29.8 and 29.4, p=.48 and p=.88). This pattern was duplicated when considering the four standard works individually. However, the fraction of top-cited scriptures on each list has gone up by an average of 4.9% per list (based on the top five, ten, twenty-five, fifty, 100, and 250 scriptures, p=.0004).

4. Do added verses have more citations than dropped verses?

This is true in all three cases. In 1986, the twenty-nine added verses had been cited an average of 4.7 times up to that point, while the 158 dropped verses had only been cited 2.6. In 2013, the sixty-five added verses had 27.0 citations to the 23.2 of the dropped verses. And in 2016, the forty-eight added verses averaged 23.0 citations, while the thirty-five dropped verses averaged 22.9. None of these changes was significant individually (uncorrected p=0.046, 0.28, and 0.99), but collectively they were highly significant (24.2 vs 14.75 citations, corrected for length of study period, p<.0001). It is worth noting that the only Old Testament scripture mastery verse that has seen a significant increase in citation rate over the study period, Psalms 127:3 (“Children are an heritage of the Lord”), was added in 2013. It is also the only verse cited in the Proclamation on the Family.

5. Do verses appearing on all lists have more citations than verses appearing on only one?

Overall, this is strongly confirmed with the 108 verses appearing on all lists cited an average of 30.9 times, nearly twice as often as the 15.6 citation average of the 214 one-timers (p<.0001). This difference is significant at the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of .0125 for all standard works except the New Testament (p=.15), because the 1963 list omitted a large number of highly-cited scriptures, so very few appear on all four lists.

Summary of scripture mastery analysis

Despite recent press releases, it is clear that the changes to the scripture mastery list do not reflect a commitment to providing equal support for each of the nine (now ten) fundamental doctrines. They do, however, represent a reasonably accurate reflection of the most frequently used scriptures in general conference, and are becoming more closely allied with conference citations in all four standard works. However, this general trend is complicated by many externalities, so simple predictions based on this rule are usually, but not always, statistically significant.

I would argue that given the two alternatives—following general conference rather than finding an equal number of verses for each funda mental doctrine—the former is preferable for at least two reasons. First, the “fundamental doctrines” do not include key gospel principles such as charity, service, missionary work, human relationships, nor (until 2016) the importance of study and knowledge; it is important that these topics receive attention anyway. Second, the most cited conference scriptures generally are Christ-centered, meaningful, and eloquent; therefore, they provide a better model for spiritual development than attempts to score a limited set of theological points. This is most noticeable in the 1986 revision of the Old Testament verses, which dropped many verses that are often taken out of context to support “restoration of the One True Church” rhetoric (e.g., Genesis 14:20, 49:22; Exodus 28:1; Deuteronomy 18:18; Isaiah 24:5–6; Jeremiah 16:17–21).

However, there are some disturbing trends noticeable as well. First, the majority of scriptures on all four lists reinforce the importance of obeying commandments and leadership, often in extremely austere tones. This privileging of authority for its own sake is unlikely to resonate with teenagers, and the absolutist tone is particularly troubling given the “crisis of confidence” currently being experienced by a large section of Church membership.Second, given that these teens spend most of their time in school and this scripture memorization is occurring within the Church Education System, one would hope for scriptures that emphasize the value of learning. However, pro-education verses like D&C 88:78–79 (“be instructed in theory, principle, and doctrine”), 93:24 (“truth is knowledge of things as they are”), D&C 130:18–19 (intelligence rises with us in the resurrection), 1 Nephi 19:23 (liken scriptures for better understanding), and Joshua 1:8 (meditate on the Law day and night) have been dropped from the current list, and many others commonly cited in conference like D&C 25:8 (Emma should give her time “to writing, and to learning much”), D&C 88:118, 109:14 (“seek learning, even by study and also by faith”) or D&C 88:19 and 109:8 (a house of learning is a house of God) have never been included at all. Although the 2016 reform explicitly addressed this deficit by adding “Acquire spiritual knowledge” to the nine fundamental doctrines, it added just one verse from this obvious list (D&C 88:118). Together, these two trends represent a profound commitment to conformity at odds with the message of the glorious, soaring gospel exemplified by Jesus and conveyed by Joseph Smith. Finally, with the exception of Ruth’s promise to Naomi (Ruth 1:16–17) and a passing reference to daughters and handmaids in Joel 2:28–29—both of which appear only on the 1963 Scripture Chase list—not a single verse is written by, to, about, or even mentions a woman. The addition of the explicitly egalitarian 2 Nephi 26:33 (“male and female…all are alike unto God”) in 2016 is such a small step in the right direction; it serves mainly to highlight the distance between the scriptural ideal and the curricular reality.

The Family Proclamation

Perhaps the distinction between revelation and informal corporate policy is nowhere more confused than in “The Family: A Proclamation to the World.” The document is labelled a “Proclamation,” a tag given to at least four previous documents that, even in aggregate, had a negligible impact on Church history.It is likely that the document was drafted by a team of LDS attorneys as a way to join anti-gay marriage court cases; it was indeed used for that purpose within months of publication, and six times subsequent to that.Despite being drafted without the input or knowledge of the women’s auxiliaries,it was read at the General Relief Society Meeting (then not considered part of general conference). It has never been accepted through a vote of common consent, but it is difficult to argue that the document is any less influential, or treated as having any less authority, than canonical scripture.

As noted in the introduction, Elder Packer’s 2010 labelling the Proclamation as “revelation” was quickly withdrawn,yet three similar statements by earlier general conference speakers have been allowed to stand,and Elder Packer again called it “another revelation” in April 2011.Sentences from the document are often excerpted to be repeated by Primary children every week for a month during “Sharing Time” in lieu of a verse from the standard works in official Church curricula (including three of the twelve “verses” for 2014, and inspiring the song for the annual children’s program called “The Family is of God”). Members are frequently encouraged to frame copies of the document and hang them in their homes. Sacrament meeting talks are often assigned based on the document. Perhaps most telling of all, general conference speakers have cited the document by name an astonishing 213 times since October 1995; by contrast, the most cited verse of scripture (Moses 1:39) has received only 80 citations in that time period. Furthermore, in the missionary manual Preach My Gospel, the Proclamation is listed under “scripture study” in a section on eternal marriage.

In addition to influencing citations, and in contrast to previous proclamations, the Proclamation on the Family breaks new theological ground by asserting in its first sentence that “The family is central to the Creator’s plan,” and “gender is an essential characteristic of individual premortal, mortal, and eternal identity,” establishing post-World War II Western gender roles as theologically and eternally correct, and foretelling an apocalypse if “traditional” families are not vigorously protected legally. These points have been roundly criticized by scholars,but adopted enthusiastically by conference speakers. The single verse of scripture used in the Proclamation on the Family itself (Ps. 127:3) had been cited just twice prior to 1990,but eighteen times thereafter (p=.02) and was added to the 2013 scripture mastery list. The ratio of the word frequency of “home” to “family” has gone from 7:10 in the mid-1970s to 3:10 today, possibly reflecting a distinction between homosexual homes and “counterfeit” homosexual families that persists in the rhetoric of some leaders despite a rapidly changing legal landscape.Despite the Proclamation’s advocacy for severely restricted women’s roles, female speakers comprise fourteen of the top forty speakers to cite the Proclamation in conference (but zero of the top thirty-eight to cite the standard works) led by Bonnie Oscarson, whose 0.68 citations per page is 135 percent higher than the most enthusiastic man’s citation rate. Overall, the citation density of female speakers is 2.3 times higher than that of male speakers (p<.0001), implying active collusion in the unequal ideation of gender roles. Interestingly, though the Proclamation has been cited in nearly half (10/22) of the post-1995 conference talks that use the word “homosexual” or a synonym, the vast majority of references to the Proclamation are not in talks regarding homosexuality (114). Rather, those aspects of the document regarding traditional gender roles seem to have more thoroughly captivated conference speakers. During the time period, discussions of “family” have continued to accelerate (increasing from just over 500 references in the 1930s to well over 3,000 references in just the first half of the 2010s), and an 800 percent increase in the use of the word “complementary” when referring to the responsibilities of men and women.Using Craig’s Zeta to analyze distinctive word use in the corpus of general conference talks before and after October 1995 reveals that assertions of the authority of Church leaders are also on the increase, with words like “authority,” “lead,” “obedience,” and “testify” all in the seventy most increased (“Proclamation” comes in at #12; the names of leaders “Monson,” “Gordon,” “B.,” and “Hinckley” all also make the top fifteen).

Not all the shifts have been regressive, however. By the same metric, the most distinctive word in the Proclamation on the Family is “adaptation,” in a cursory acknowledgement that not all fifteen million LDS members live in two-parent nuclear families. This word had been used only twice before in general conference, neither time in reference to family circumstances, but has been used seven times in reference to families since then. Similarly, references to “women” and “daughters” have increased while “man,” and “man’s” have decreased. References to “heavenly parents,” though uncommon through most of LDS history (0.22 references per year from 1851–1994) have increased ten-fold since the phrase appeared in the Proclamation on the Family (2.37 references per year from 1995–2015).

Thus, although collectively there appears to be unwillingness to declare in writing that the Proclamation “fits the definition of a revelation” even when asserted by the President of the Quorum of the Twelve, there is no such hesitation to treat it as such. This demonstrates just how much like normative scripture even ostensibly non-obligatory policy statements can function in the modern LDS Church.

The Gay Exclusion Policy

While this paper was under review, the question of what aspects of Church government are decided by leaders acting on their own, and which are directed by God, was further confused by changes to the Church Handbook of Instructions. Although the handbook is ostensibly available only to members of the LDS all-male hierarchy, these changes were noted and discussed online and in the press in early November 2015, before the hard-copy version had been distributed. These changes mandated a disciplinary council for any member in a legal same-sex marriage,refused baptism to the children of gay parents until age eighteen, and allowed baptism thereafter only if the child “specifically disavow[ed] the practice of same-gendered cohabitation and marriage [and did] not live with a [gay] parent.”

The press response to this action was strongly negative. The day after Church spokesman Spencer Hall confirmed the reports, University of Utah professor Jonathan Park blasted the changes in the campus newspaper as “a pestilent, homophobic plot to alienate and embarrass the children of same-sex couples.”Jana Riess, in a “livid” blog post quoted by the New York Times, called it a “hearbreaking . . . impossible choice: . . . be excluded from lifelong love and companionship, or excluded from the blessings of the church.”An organized mass resignation event attracted fifteen hundred participants in downtown Salt Lake City on November 14th, some waiting in line more than an hour-and-a-half to officially remove themselves from the institution.

The LDS Church responded with a carefully scripted interview between the managing director of LDS Public Affairs, Michael Otter son, and Elder D. Todd Christofferson, where Christofferson claimed the policy was designed to avoid “difficulties, challenges, conflicts that can injure development in very tender years” of homosexual couples’ children.Negative reactions continued, suggesting that this explanation was not universally convincing. On an international podcast, attorney James Ord speculated that the motivation for the policy change was primarily limiting legal liability.In a podcast that received approximately five times more downloads than usual for Rational Faiths, Elder Christofferson’s own brother Tom described the situation as “dreary,” but encouraged “all of us who have had our hearts broken by this to reach out much more in love and acceptance to those who are affected by this.”

Then, in January 2016 quorum president Russell M. Nelson declared at an internationally broadcast fireside that:

The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles counsel together and share all the Lord has directed us to understand and to feel individually and collectively . . . . This prophetic process was followed in 2012 with the change in minimum age for missionaries and again with the recent additions to the Church’s handbook . . . . We met repeatedly in the temple in fasting and prayer and sought further direction and inspiration. And then, when the Lord inspired His prophet, President Thomas S. Monson, to declare the mind of the Lord and the will of the Lord, each of us during that sacred moment felt a spiritual confirmation. It was our privilege as Apostles to sustain what had been revealed to President Monson.

At this point, Elder Nelson had asserted unilaterally that the change in missionary age policy and the gay exclusion policy—despite referring to them as policies—were nevertheless arrived at by divine “inspiration,” “revealed” to a prophet, and confirmed by the Holy Ghost to Church authorities. This effectively erased the line between policy and revelation. Even the language Elder Nelson used seems to deliberately parallel the only other unquestioned revelation in living memory, Official Declaration 2, which ended the racial priesthood and temple ban: “we have pleaded long and earnestly in behalf of these, our faithful brethren, spending many hours in the Upper Room of the Temple supplicating the Lord for divine guidance. He has heard our prayers, and by revelation has confirmed that the long-promised day has come. . . . It was then presented to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who unanimously approved it. . . .”Nevertheless, Elder Nelson’s talk was given in an unofficial setting (albeit widely seen and reported), and in the following months and general conferences, the assertion was never corroborated by President Monson or any other apostles.

However, in June 2016 the Church released the new curriculum for their seminary program, Doctrinal Mastery New Testament Teacher Material.The lesson on “Prophets and Revelation” distinguishes between policy and doctrine, but suggests that both are revealed by God, and students are marked wrong if they did not recognize the uncanonized Proclamation on the Family as “Eternal Truth.” The lesson also quoted from Elder Nelson’s talk that called the gay exclusion policy revelation, and it repudiated the idea that this “revelation” might change due to social pressure.

In the space of twenty-four hours in early September 2016, the online version of the manual went through at least three revisions and the idea that Church policies are revealed from God and the quote from Elder Nelson’s talk were excised, reinstated, then excised again.The quick tempo of all these drafts, which somehow were made public while still being edited, indicates that the confusion about which rev elations are binding on Church members is widespread even among employees with decision-making authority over the curriculum. However, the fact that the assertion of “eternal truth” was ultimately retracted for both the Family Proclamation and gay exclusion policy suggests that the impulse to authoritarianism is being, barely and belatedly, held in check. Nevertheless, Elder Nelson’s talk that suggested that the gay exclusion policy is revelation was published in the October 2016 Ensign.

Conclusions

Joseph Smith’s descendant Paul Edwards once stated: “How do Mormons use scripture? They don’t. It is my observation that very few Mormon ministers use scripture at all. When they do, they use it to give legitimacy to what they have already decided to do.”This strategy is hardly unique to Mormonism, and was pithily captured in a quote attributed to Andrew Lang, as the way “a drunken man uses lamp-posts, for support rather than for illumination.”In recent decades leaders have put remarkable emphasis on uncanonized texts, claiming divine inspiration in language remarkably similar to previous descriptions of now-canonized texts.

Attempts to create constructive, friendly, and robust theological discourse have often been suppressed by Church leaders. One poignant example is the excommunication of Paul and Margaret Toscano for their generous and thoughtful book Strangers in Paradox.Unfortunately, additional examples abound. However, it is not impossible for scholars to shape Church discourse in a broader perspective, though they almost uniformly pay a high price for doing so. Lester Bush’s Dialogue article on the history of blacks and the priesthood is a prime example.Then-editor Robert A. Rees commented “The effect of our publishing this exchange was to clarify many points of misunderstanding and dispel much of the myth that has circulated in the Church regarding the Negro doctrine, and, further, to put the discussion of this subject on a more rational (and hopefully more spiritual) level.”Several General Authorities are reported to have read the essay, even before it was published, and it is widely seen as contributing to the 1978 revelation. Nevertheless, Bush faced remarkable pressure and obstruction at every level in his research, publication, and post-publication life, and was made unwelcome in, then left, the Church.

Similarly, Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery published Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith in 1984, and since then the generally hostile attitude toward Emma Smith has shifted dramatically. In the very next general conference, President Hinckley broke with prior tradition and praised Emma by name a total of twelve times.From 1974 up to the publication of Mormon Enigma, Emma was mentioned only sixteen times in general conference, and 62.5 percent of them were in an unflattering way. Since then, she has been mentioned on average more than once per conference and 74.6 percent of those in a positive way (Fisher: OR=4.7, p=.008). However, both Newell and Avery faced significant backlash from the Church at several levels, and they and their children have become disaffected from the Church.

In the aftermath of the Ordain Women event at the October 2013 general conference, the internet came alive with people loudly arguing about the movement’s merits, and both sides spent a good deal of time quoting speakers from that very general conference, and less time quoting canonized scripture. This clearly indicates that conference addresses play the primary normative role in the modern Church. While Church leaders have resisted commenting on the Ordain Women movement, several people involved in it have faced disciplinary action, including the excommunication of Ordain Women’s organizer Kate Kelly in June 2014.

The hardline retrenchment witnessed in the gay exclusion policy and reinforcement of rigid gender roles appears to have triggered a wave of resignations from the LDS Church. While statistics from the institution are not available, some circumstantial evidence exists nonetheless. For one, there have been mass resignation events. A broader view comes from an analysis of official membership statistics (see table 5). Every April general conference, a secretary to the leadership presents a list of statistics to the Church, including the total membership, number of new children joining the Church, and number of converts. By comparing totals from year to year, it is possible to calculate the number of people leaving the Church, whether by death, excommunication, or resignation. It should be noted that these totals appear to not be complete at the time they are presented, as the growth and loss figures show a great deal more instability than seems reasonable, so the results for any one year should be viewed with some skepticism. However, inferences based on long-term trends are more likely to be valid. To show how much resignation has increased in the last few years, I generously assume that no members left the Church due to excommunication or resignation prior to 2013, and all losses were therefore due to death or the removal of unbaptized children of record. This establishes a reasonable death and/or removal rate of 4.558 per 1000, consistent with a membership primarily in the developed world. Holding that rate constant indicates that 123,688 members resigned or were excommunicated in the last three years.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 5, see PDF below, pp. 133–135]

While this value is only a rough approximation based on reasonable assumptions, it strongly suggests there has been a sharp change in retention, and Church leaders apparently have contradictory ideas about how to respond. Nevertheless, one thing we can count on: whatever General Authorities decide to do, we will hear about it at conference, with selective quotes from the canon, that will form our new, unique, and ever-evolving Mormon scripture.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue