Articles/Essays – Volume 55, No. 2

Dialogue and the Daring Disciple

One thing a reader learns from Terryl Givens’s new biography is that no one who knew Eugene England could claim to be an objective appraiser of his life. Countless individuals revered him; he had guided and accompanied them on their life journeys. Some individuals distrusted him, couldn’t reconcile their approaches to religion with his pleas for dialogue and his challenging questions. In the preface and introduction to Stretching the Heavens, Givens briefly acknowledges his own debt to his subject.

Gene’s wife Charlotte asked Givens to take on the project, promising him access to journals, correspondence, and other materials not included in the two-hundred-box collection archived at the University of Utah (by Gene’s granddaughter Charlotte Hansen) after his passing in 2001. Givens relies on these materials plus articles and interviews to create a painstakingly annotated book. He paints a portrait that reveals the greatness, the goodness—and the vulnerability—of Gene England. He also shows us how Gene fit—and didn’t fit—into his Mormon world.

Givens depicts Gene as a devout disciple of Joseph Smith. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was as vitally important to Gene as the air he breathed. But—and this is the dilemma he faced most of his adult life—what do you do when your conscience conflicts with the institution to which you have pledged loyalty?

Lowell Bennion, founder of the University of Utah LDS Institute of Religion, quickened Gene’s conscience. Gene confesses that he, as a young student, accepted the traditional reason for Black members not having the priesthood and temple privileges, until Brother Bennion encouraged him to reexamine his views. Gene absorbed Bennion’s practical, humanitarian approach to religion. Twenty years before Gene would find himself at odds with the LDS hierarchy, Lowell Bennion would be dismissed from the Church Educational System for his openness to reason and science.

Givens seems surprised that Gene didn’t learn from Bennion’s experiences that the Church in the last half of the twentieth century was not receptive to what would become the trademark of Gene’s own endeavors: dialogue. The name of the journal that he and the four other founders decided upon would govern all of Gene’s efforts to reconcile conscience and the Mormon establishment. Having worked closely with students at the University of Utah and at Stanford, he knew how many were troubled about Church history and policy and about what seemed to be an institutional disregard for the exchange of ideas. If they could have real dialogue, perhaps the seekers could find what they needed.

Givens is also astonished that Gene didn’t learn from his own experiences. He was constantly reprimanded for his efforts to espouse a thoughtful, humanitarian religion and consistently thwarted in his attempts to open dialogue with various General Authorities, sometimes those least sympathetic to his views. Despite the evidence, Gene seemed to have a hard time believing it was his association with Dialogue that stood in the way of employment at Brigham Young University; he would finally resign from the journal’s board and be hired. Givens documents the indignant responses of fellow BYU faculty member Joseph McConkie and his father Bruce R. McConkie to Gene’s popular honors lecture on the progression of God. The McConkies were not amenable to dialogue; in a letter to Gene dated February 19, 1981, Bruce McConkie wrote, “It is my province to teach to the Church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo what I say or to remain silent” (167).

Most amazing to contemporary readers, perhaps, is the access that Gene had to the General Authorities, in particular Boyd K. Packer, who responded to Gene over the pulpit, in his office, and in letters. Gene frequently voiced his concerns to men he thought might be more sympathetic—Marion D. Hanks, Neal A. Maxwell—but was often dissatisfied with their reactions too. Still, not only did they grant him audience but they usually responded to the letters in which he pled for acknowledgement of his good intentions and for understanding of his views.

Those views, Givens reiterates, were predictably dangerous for a man who wished to be employed by the Church. He opposed war; he espoused feminism. He defended Fawn Brodie’s research and praised Levi Peterson’s fiction. He participated in Sunstone symposia. He embraced what threatened the twentieth-century Church and Church Educational System: freedom of discussion, dialogue. In his chapter headings, Givens labels Gene “A Polarizing Disciple” and refers to “The Perils of Provocation” and “A Dangerous Discipleship.”

Givens sees Gene as almost oblivious to the probable consequences of his words and actions. “One cannot fully fathom the heart of the man or the tragedy of his life,” says Givens, “if one does not see his tragic flaw as a persistent, willful, naiveté” (107). Those who fought with Gene on the battlefield (pardon, Gene, the war metaphor) would probably describe him as persistent, willful, but not naïve. His eyes were open. He knew what he was doing when, as soon as Lavina Fielding Anderson concluded her August 1992 Sunstone Symposium talk with the revelation that the Church kept secret files on some members, he leapt to his feet to name and censure the Strengthening Church Members Committee. Those of us present saw a man passionate about his causes, with enough hope to keep pressing on, no matter the outcome. He stretched his own vision of the Church into what might be heaven, a paradise that embraced, that loved all humankind.

Stretching the Heavens is a sad book. Charlotte told me she cried after she read the first draft. The book is sad because the church that Gene “loved too much to either leave or leave alone” (136) couldn’t give him what he wanted: a more humane institution and affirmation that he was a worthy disciple. The twenty-first-century Church might afford him at least the latter; the opinions he suffered for might not alarm the current hierarchy—at least not so much.

Gene is in large part responsible for those changes. “The Crisis of Modern Mormonism,” the last half of the book’s subtitle, is still accurate; the Church is losing some of its brightest and best because of adamant positions on women and LGBTQ issues. But there has been a willingness to acknowledge some past problems. There has been more dialogue—and that affords a tempered hope. Givens closes the book with Douglas Thayer’s image of Gene doing something that gave him great pleasure—fishing. Gene used a long rod, one that might reach far, perhaps in years as well as yards. He “lived his life well and liked to make long casts” (284). Terryl Givens has documented the sorrows of that life and the promise of the long casts—stretching, perhaps, to the heavens.

Personal disclaimer: In writing this review, I found myself unable to refer to Gene by his last name. I too am one of those enormously affected by his ideas and his ways of expressing them. In the English graduate student study on the Stanford Quad, Gene would sit at the front table with his books spread out before him. I would pull out the chair across from him and narrate the woes and wonders in my life. His patience, I understand now, was astounding. He and Charlotte trusted me with their children; I was proud to be a frequent babysitter. Worried that I might starve before I found work, Gene devised a new job—office manager for the newborn Dialogue. I managed to disorganize Wes Johnson’s campus office, the journal’s home.

Many years later, in 2007, Toby Pingree invited me to participate in Sunstone’s panel Why I Stay. My presentation pays homage to Gene’s memorable essay “Why the Church Is as True as the Gospel,” but not just the main theme. At the start, Gene tells of being a restless twelve-year-old in a stake conference when he saw the “transfigured face of Apostle Harold B. Lee . . . giving the new stake an apostolic blessing,” and because Gene was there, he felt “the presence of the Holy Ghost and the special witness of Jesus Christ.” This is why I have stayed in the Church—because I have been touched by others, like Gene, who have stayed—and because if I am there, I too may someday feel that hope and holiness.

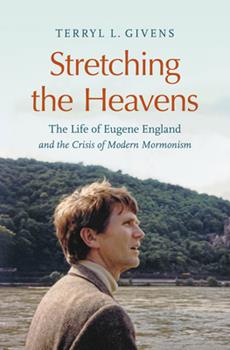

Terryl L. Givens. Stretching the Heavens: The Life of Eugene England and the Crisis of Modern Mormonism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021. 344 pp. Hardcover: $34.95. ISBN: 978-1-4696-6433-0.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and biographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue