Articles/Essays – Volume 52, No. 4

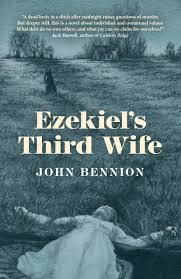

Death in a Dry Climate | John Bennion, Ezekiel’s Third Wife.

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Rachel O’Brien Rockwood Wainwright Harker—the narrator and eponymous heroine of John Bennion’s new mystery novel Ezekiel’s Third Wife, has four last names, none of which is superfluous. Together, they tell a remarkable story about our heroine in the years before the novel begins. Here is the digest version.

Timothy O’Brien, Rachel’s natural father, was an abusive drunkard who Rachel’s mother walked out on when she was eleven years old (she is twenty at the start of the novel). And Ezekiel Wainwright, the polygamous Mormon storekeeper to whom Rachel was married at eighteen, has been sent to England on a mission for the Church—where, in violation of the recent Manifesto by Wilford Woodruff, he has courted an even younger woman to be wife number four. Both men function in the narrative only as absences, but they are profound absences who leave behind gaps and holes that shape the narrative in important ways.

The other two last names belong to the most important men in both the story and in Rachel’s life. The wealthy Mormon rancher and tracker J. D. Rockwood became Rachel’s stepfather when her mother joined the Saints and became his fifth wife. When Rachel’s mother died, J. D. kept Rachel in his home and treated her as a favorite daughter. In the community, which is also named Rockwood, J. D. is both feared and revered—much like the historical Porter Rockwell, upon whom (I strongly suspect) he has been very loosely based.

Rachel’s final name comes from Matthew Harker, her childhood sweetheart from her days in Nevada, who finds her a year after she marries Ezekiel and convinces her to become his legal wife, her marriage to Ezekiel being an ecclesiastical union only and not sanctioned by the law of the land.

Ezekiel’s Third Wife begins just two weeks after this secret marriage. Ezekiel is still in England, J. D. is still tracking down bad guys, and the desert community of Rockwood has been rocked by a series of water disputes. In good Mormon fashion, the bishop has appointed one of his counselors to be the water master and to apportion the town’s scarce supply. Crops are failing, and the entire community is threatened with starvation in the coming winter. Everybody needs water. Some people are willing to cheat to get it—and, just possibly (this is a murder mystery after all), to kill for it.

The dead body belongs to Ezekiel’s second wife, Sophia—who Rachel finds quite dead in an irrigation ditch with a gash on her head. To make matters interesting, Rachel discovers Sophia’s body on her way to a conjugal visit with her secret husband, who is now working as a wagon driver so he can manage occasional and highly secret visits to Rachel’s family barn. When she finds her sister wife, Matthew is nowhere to be seen—but he has left his gentile tracks all over the crime scene to be discovered by J. D. Rockwood, whose tracking skills and penchant for rough justice are both legendary. All of this sets up the body of the novel, which consists of Rachel trying to find Sophia’s real killer so that one of the most important men in her life doesn’t kill the other.

One of the great strengths of the novel is that it refuses to traffic in either stereotypes or easy answers. With only a few tweaks, Rachel’s story could become Riders of the Purple Sage—or any one of the dozens of dime novels upon which the Zane Grey novel is based. But Rachel is no Jane Withersteen. She loves her stepfather, respects the members of her community, and genuinely believes in the spiritual power of the Mormon faith. And Matthew Harker is no Lassiter. He has a last name, for one thing, and he is animated by a positive love for Rachel and not a bitter hatred of all things Mormon. Rachel must make serious choices throughout the novel, but it never does us the disservice of portraying any of these choices as easy.

Polygamy especially is treated as the enormously complex institution that it was. Rachel does not entirely reject the institution of polygamy, which allowed both her and her mother to escape from an abusive man and enjoy the protection of nurturing family. And the community of sister wives created by Ezekiel’s marriages provides a lot of support in his absence. One imagines that there would have been a lot more suffering in the world if he had only had one wife to abandon in the service of the Church.

What Rachel does entirely reject, though, is the patriarchal assumption that only men should be able to marry multiple partners. If she can be Ezekiel’s third wife, she reasons, then there is no good reason that Matthew cannot be her second husband. What’s sauce for the gander must be equally saucy for the goose. This assumption places her directly at odds with her community, but it also serves as a thought experiment to test all of the non-patriarchal defenses of polygamy that twenty-first century Mormons have created to try to make their nineteenth-century ancestors seem a little less weird. Polygamy, we like to tell ourselves, made sure that everybody had a home and a family. It provided husbands for all of the widowed women and fathers for all of the orphaned children. And it allowed the Saints to prosper in the harshest of deserts. Perhaps, Rachel suggests, but all of these objectives would be served by allowing a woman whose husband has abandoned the family in the service of the Church to take a second husband too.

The polygamous families in Bennion’s world work well sometimes, sort of, in a limited way, but they also have systemic issues that produce problems that cannot be solved. Much the same can be said of the community built around them. The defining characteristic of Rockwood is its lack of water. In response, the town’s Mormons (and everybody in the town is Mormon) practice a strict rationing system—a sort of aquatic united order. This, they believe, is how you build Zion in the desert.

Except when it isn’t. Because even faith can’t prevent what Garrett Hardin described in 1968 as “the tragedy of the commons.”Simply put, creating a common resource incentivizes cheating by creating huge rewards for being the only one who doesn’t follow the rules. When this happens in Rockwood, it exposes the fractures in the community and leads to scapegoating, ostracism, and, ultimately, murder. These things, perhaps, represent the downside of Zion.

But Ezekiel’s Third Wife is not a treatise about early Mormon polygamy or the fault lines of communitarianism or the tragedy of the commons. It is a murder mystery, and we must ultimately judge it on how well it does the things that murder mysteries are supposed to do. This includes getting somebody killed, devising an interesting puzzle, raising the stakes for solving the puzzle, introducing a compelling sleuth, and creating an engaging theory of detection. Bennion does not disappoint in any of these areas. The puzzle is compelling, and the stakes could not be higher—and the detecting team of J. D. Rockwood and Rachel O’Brien Rockwood Wainwright Harker adds something unique to the annals of detective fiction.

It’s not just that Rachel is a polygamous wife and J. D. is a gunslinging Danite—though one rarely sees such characters as anything other than stock villains in the mystery genre. Rachel and J. D. do their detecting through a wonderful synthesis of their very opposite characteristics. Rachel works through empathy and imagining herself in the shoes of the killer; J. D. works through physical evidence and deduction. J. D. is obsessed by justice; Rachel is consumed by mercy. J. D. works to please only God; Rachel tries to please J. D. And neither of them can succeed without the other, as Rachel herself articulates in a description of a previous case that they solved together:

My approach had been to look at the people, trying to figure out who had reason to kill. My approach failed because everyone in Centre had reason to want the federal deputies dead. Everyone we talked to seemed guilty. What happened was that the killing was done for a reason no one thought of, a paradoxical reason. What led to the conclusion was belief that both the physical evidence, and the evidence of people’s motives and character could solve the crime—that and reliance on the good sense of a meddling old woman in town, a woman J. D. had not respected. (170)

The story that Rachel alludes to here is told in Bennion’s novel An Unarmed Woman, which was published earlier this year by Signature Books and which is set three years before the events in Ezekiel’s Third Wife begin. By the normal conventions of the mystery genre, this would make An Unarmed Woman the first volume in a running series. But this is not, according to the author, how the two novels evolved. “I wrote Ezekiel’s Third Wife first,” Bennion reports, “then the idea for An Unarmed Woman came into my mind, and I knew it was about Rachel as an unmarried woman. So I went back and wrote that novel.”

Technically, this makes An Unarmed Woman a prequel—like The Magician’s Nephew or The Phantom Menace. But what it really means is that these are two separate novels with two different publishers that (because different publishers work at different speeds) happen to have been published within a few months of each other in a sequence that mirrors the timeline of the storyworld. Neither one depends on the other, and they can be read profitably in any order. They are united only by a common set of characters and the considerable craftsmanship of their author.

And Ezekiel’s Third Wife is, above all else, a well-crafted story. It takes on a lot of big issues—polygamy, desert communitarianism, water rights, patriarchal culture, loyalty, belonging, and Mormon identity— and never feels like it is trying to do too much. But it still manages to be a cracking good murder mystery with a completely logical solution that I, for one, never saw coming. And it is in every way that matters an enormously satisfying book.

John Bennion. Ezekiel’s Third Wife. Winchester, UK: Roundfire Books, 2019. 232 pp. Paper: $15.95. ISBN 978-1- 78904-095-1.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue