Articles/Essays – Volume 47, No. 3

Crossing the Planes: Gathering, Grafting, and Second Sight in the Hong Kong China International District

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Our strength lies in shifting perspectives, in our capacity to shift, in our “seeing through” the membrane of the past superimposed on the present, in looking at our shadows and dealing with them.

Hong Kong, Dan Rather declared as he began his television coverage of the 1997 “handover” from British to Chinese sovereignty, “is Asia for beginners.” That is what it was for me, although it has been my home now for more than twenty years. In all of that time and in all of my work on American culture in transnational contexts, considering how people are changed by their cross-cultural encounters, I have never written about Mormonism and its various crossings in Asia. Although I have no doubt that my beliefs infuse my professional work, as I thought about Asia in my Mormonism, trying to parse influences and see where the academic training and the Mormon upbringing inform one another became impossible. So I have given in to the blurring of boundaries and I embrace the amorphousness of what follows, but I warn the reader that it is a bit of pastiche: somewhere between an academic treatise, a class lecture, and a sacrament meeting talk. Fortunately, Hong Kong is and always has been, as historian Elizabeth Sinn notes, a “between place.”As a twenty-first-century Latter-day Saint woman living in Asia, I am constantly reminded of the ways in which the crossings that take place today are in planes rather than across plains as they were in the nineteenth century.

My thoughts here are informed by my work in transnational American studies, which consider how “America” looks from the outside in, with a particular emphasis on the intersectionality of gender, national identity, and generation/history in Hong Kong as it is observed in women’s narratives of their cross-cultural encounters. Although I am partial to a post-national/ transnational view of the world (national identity is but one of many identifying threads in a particular individual or community in globality), clearly, notions of nationhood and national exceptionalism (particularly American and Chinese) still matter a great deal in Hong Kong and, I would argue, in much of Asia as well as elsewhere in the world.

Additionally, because national myths and values, particularly processes of Americanization, are, at times, still powerful influences shaping cross-cultural interactions in Hong Kong, within LDS congregations individual Church members often draw upon what they believe to be true about a particular nation or culture to affirm personal decisions or worldviews, including doctrinal opinions and/or spiritual core values. To use the nomenclature of gathering and grafting as it is deployed in the parable of the olive tree in the fifth chapter of Jacob in the Book of Mormon, each of us grafts our experiences onto our beliefs as we gather together in the larger communities in which we worship. Macro and micro histories are in constant tension and our pasts shape our present in profound but subtle ways. As borderlands studies scholar Gloria Anzaldua reminds us above, strength comes in “seeing through” the past, “looking at our shadows and dealing with them.” Only when we understand what has been is it possible to truly shift our perspectives and change in ways that strengthen in the long term.

In Hong Kong, I have witnessed a number of Latter-day Saints in various stages of “seeing through” their pasts, grafting expe riences onto belief (or vice versa) as they transit back and forth across the Pacific, gathering in various LDS congregations and imbibing elements of a host/national culture that often grafts onto a home/national culture. Their stories shed light on changes that have occurred over the past decades in both Hong Kong and North America, particularly in terms of post-1965 immigration to the US and the “brain drain” from Hong Kong/greater China between the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in the PRC and the 1997 resumption of Chinese sovereignty marking the end of British colonialism in Hong Kong. Latter-day Saints in Hong Kong include members of the Asian diaspora who were born and raised in North America or in other western countries as well as children of the brain drain, which is now reversing as opportuni ties in Asia are on the rise.

The anecdotes and individual case studies discussed hereafter are suggestive of broad trends and demographic shifts in many parts of the world where Mormon congregations are becoming more diverse and increasingly dependent on diasporic souls as leaders as well as followers. They have been gathered via my own participant observation as a member of the LDS Church in Asia, email exchanges, and focused personal interviews conducted over the past two years. This exercise in narrative enquiry focuses on Latter-day Saints who are or were members of the Hong Kong China District (formerly known as the Hong Kong International District), the setting with which I am the most familiar and where I serve, currently, as a district Relief Society president. What follows is a glimpse of several individual “case studies” followed by a slightly more detailed discussion of one particular group of Church members in Hong Kong, domestic workers from the Philippine Islands.

The district is, to use Mary Louise Pratt’s terminology, a contact zone, a place “where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical rela tions of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today.”More specifically, Hong Kong, as a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People’s Republic of China, is both postcolonial and still beholden to a new hegemon in Beijing. It is also a site of American neocolonialism. Hong Kong is a unique backdrop for Latter-day Saint community formation. Mormonism, as an increasingly global religion, finds its way within the contact zone of Hong Kong in multiple ways.

I have argued elsewhere that there have been, historically, several types of “troubling” American women in the contact zone of Hong Kong. Sometimes troubling refers to ethnocentric, exceptionalist, or culturally insensitive behavior expressed by privileged American women (often, although not always, Caucasian) who express their views with particular confidence even though at times they may feel (or actually be) quite marginalized within Hong Kong society. The colonial mindsets that linger after the sunset of the British Empire in Asia often morph into expressions of American exceptionalism or neocolonialism in Hong Kong, which is still a very stratified society where “expatriate” and “local” populations often have frequent surface contact but little deep interaction.

Although as Latter-day Saints we often think of ourselves as the literal or figurative descendants of poor and marginalized pioneer predecessors who crossed the desert plains in homespun simplicity, or we may feel the sting of persecution in our own lives as we defend particular principles or values, in postcolonial Hong Kong there are additional realities to consider. Most Americans who come to Asia to live and work are privileged rather than persecuted souls, crossing back and forth in jumbo jets rather than covered wagons. Many, if not most, have greater access to material wealth and opportunity than they would have had they stayed in the US. (Although there always have been and are, increasingly, affluent Chinese residents of Hong Kong—many of whom come from the Chinese mainland—as well as US citizens who are not particularly affluent, a majority of Americans who are most visible at church still earn high salaries and enjoy varied benefits such as club memberships, school subsidies, and opportunities for travel, although at reduced levels when compared to the pre-1997 era.)

As the memory recedes of both British colonialism in Hong Kong and Western imperialism in China, and there is talk of the “rise of China” in media coverage, there is a lingering awareness of—and aversion to—those who continue to exhibit colonial attitudes. For that reason, utterances that reflect Mormon and/ or American exceptionalism at Church (which are generally well-meaning albeit annoying to those who are recipients of what I call “the pedagogical impulse”) can be somewhat alienating or divisive even though interactions generally remain cordial. In fact, my book on the pedagogical impulse, and on the intersection of gender and American exceptionalism in Hong Kong, had its genesis in a moment when a Japanese sister at church asked me with genuine curiosity, “Why is it that American women are always trying to teach me something?” The divide in our Hong Kong LDS community is, unfortunately, widened by the fact that Cantonese-speaking and English-speaking congregations meet separately. The original purpose of forming a separate district in Hong Kong was to give all non-Cantonese speaking Latter-day Saints a place to worship and serve (there is a small Mandarin Chinese-speaking branch in addition to the English branches) but an unfortunate outcome of this partitioning is the limiting of interactions across linguistic (and often cultural) difference.

Although my published work to date has focused on women’s narratives of cross-cultural encounter, it is not just American women who manifest strains of exceptionalism or take a teaching tone with others. American men can exhibit exceptionalist attitudes of various types as well. And for both women and men, the mode of exceptionalism can often boomerang back at the “folks back home” (in Western societies) who are seen to be less cosmopolitan in their views. One example of this boomerang exceptionalism within the LDS cohort in the greater China region is the “Mormon China hand” phenomenon that I have written about elsewhere. These individuals are men (and a few women) of various generations, ethnic identities, and cultural backgrounds who are deeply and personally invested in the people, cultures, and languages of Asia, particularly China.While they are a highly diverse lot, they do share certain common traits: all served (or are related by birth or marriage to those who served) Chinese-speaking missions (most in Taiwan or Hong Kong although there are in the younger cohort those who have been sent to Mandarin- or Cantonese-speaking missions elsewhere); all enthusiastically embrace the effort to help “build the kingdom” in Asia, and many have returned to the greater China region to live, work, and teach. Those who have left Asia often maintain ties with China and Chinese culture in their professions and personal lives in the US and elsewhere.

Because many of these individuals are confident sharing their insider knowledge of a place and society they have come to know and appreciate, at times their rhetoric morphs with that of earlier generations of those who sought to “save China” in various ways. Such individuals are the latest in a long line of Americans who have grafted national onto religious identities in their experiences in the region. At work or at church they thrive on bridging cultural difference, seeking to fill gaps in others’ knowledge. Predictably, they articulate a range of ideological and political perspectives as they bridge. Some sound to me like throwback Cold Warriors saddened by the “loss” of China to the Communists, while others are anxious to move American attitudes out of the past and into globality. All are keen to counter China bashing in the US.

Some “Mormon China hands” have attracted significant national and international attention in speaking about the Sino US encounter in the contemporary moment. The most visible manifestation of the LDS-affiliated pedagogical impulse was on display in the 2012 Republican Primary debates when the two Mormon presidential candidates locked horns over the question of Sino-US relations. John Huntsman reprimanded Mitt Romney—in the Mandarin Chinese he learned on his LDS mission to Taiwan—for his naivety about life in the “New China.” Brand ing Romney as naïve and out of touch with changes taking place in China—Romney had already branded Huntsman as a traitor to the Republican Party for accepting President Barack Obama’s appointment as Ambassador to China—Huntsman subtly manifested the missionary exceptionalism that I hear articulated from time to time at church.

My emphasis here, however, is on another definition of troubling: troubling as unsettling or changing assumptions about what has been seen as the institutional or communal norm. One unanticipated outcome of my research on American and “Americanized” women in Hong Kong over the course of the past two decades has been a greater awareness of the ways in which people of Chinese descent, particularly younger Chinese women who spent time in the US and then returned to Hong Kong to live or work or study, were seen as troubling when they “acted too American” in Hong Kong society. (Grace Kwok’s work on LDS women in Cantonese-speaking congregations in Hong Kong confirms this assertion in rich detail.) Hong Kong is an ideal place to observe transnational and transcultural lives and manifestations of various identities (national, gender, ethnic, religious) and their connections to past events. It is where “old” and “new” Asia meet and the children of diaspora trouble and unsettle—in quiet but significant ways—monolithic narratives about Mormon identity in the contemporary world.

In her article, “How Conference Comes to Hong Kong,” Melissa Inouye, who belongs to a family familiar with transpacific crossings in planes as well as in mindsets, captures what so many of us who live and worship in Hong Kong feel when she writes:

Hong Kong is famous for its diversity and discontinuities. Its tiny borders create a crowded space for the confluence of wealth, poverty, tradition, transience, centrality, marginality, urban, rural, East, West, and nearly everything else. In Hong Kong, Mormonism comes into focus as a dynamic global religion in which powerful forces of homogeneity and heterogeneity exert themselves side-by-side.

Inouye has argued, “While the administrative center of the LDS Church is unquestionably Salt Lake City, Mormonism has other centers and other peripheries.” I would add that Hong Kong is a center within the periphery and that the Hong Kong China District is on the periphery of the Church in Hong Kong. By that I mean that the majority of Latter-day Saints (like the approximately 95 percent of the general population) who live in Hong Kong are Cantonese speaking and ethnically Chinese. But the small cohort of individuals who are members of the Hong Kong China District are actually an important community to consider in the development of Mormonism in globality. Many within this population belong to the Asian diaspora that has, for generations, been moving between nations, congregations, and social contexts, negotiating between home and host cultures as well as Wasatch Front and more localized expressions of Mormonism. These individuals are gatherers and grafters and exemplars of “shifting perspectives/seeing through” the membrane of the past who trouble (in positive ways, I think) stereotypical definitions of Mormonism, gender, and national identity in both LDS and their respective Asian cultures. Some have US passports but many do not. All have been shaped by a church culture that is infused by certain aspects of American culture and values.A few of their stories are briefly considered here, and they suggest the challenges and opportunities facing the LDS Church as it transitions from a North American to a global entity.

Complex Legacies: The Americanization of Hong Kong Latter-day Saints

I begin with the story of a woman who is highly articulate about the identity work she has had to do grafting experiences onto belief over time. She prefers that her real name be withheld and I will refer to her as Sharon. Born in 1967, the year the Star Ferry riots marked a watershed in local Hong Kong Cantonese-speaking identity (forcing colonial government officials to respond to local concerns), Sharon converted to Mormonism as a teenager, attended BYU Hawai’i from 1986-1988, then served a mission in Hong Kong and returned to Hawai’i where she finished her education and married. Sharon’s story is one of multiple crossings via marriage (she married a Caucasian man who was born and raised in the Western US), education, and worship. Sharon and her biracial/bicultural children move between local and expatriate branches in Hong Kong depending on the circumstance. Sharon’s older children are enrolled in a Cantonese-speaking seminary class, but the family attends Sunday meetings in an English-speaking, highly Westernized congregation.

Raised mostly by her paternal grandmother (her father was “left behind” in China), Sharon attended an all-female secondary school in Hong Kong. She describes her childhood environment as “female-oriented” —including the “portrait of Queen Elizabeth [that] was prominently displayed in every government office and on our currency.” Countering Western stereotypes of Chinese culture as patriarchal, Sharon declares, “My grandmother and mother never/rarely taught me to be a submissive wife or anything to do with my role as a woman, unlike what I was taught in the Mormon Church. Instead much emphasis was placed on getting educated so I would be able to make a good living. Perhaps it was because Grandma and Mom always had to fend for themselves.”Sharon’s experience runs contrary to that of many LDS women I have known in Asia who joined the Church because they found it a more benign patriarchy than that which they knew in their childhoods.

Sharon appreciates the direction that an immersion in the LDS community provided. “I always thought I should try to get good grades and everything would work out. I never thought about my future beyond that. It was the Mormon Church that helped me ‘map out’ my future, put it in more concrete terms when I became a member at 15.” Sharon realized that she would have to make some adjustments to the more “male dominated world” of the Church, but the tradeoffs seemed worth it and she describes herself as “happy to go along” as “after joining the Church, I felt like Americans, especially American Mormons had it all figured out.” After all, she recalls, “they (the missionaries) seemed so pure and kind, and most of all the white American males were the ones that ran the Church. And of course Jesus looked white and so did Joseph Smith. . . . I felt like they had come to rescue this confused and poor Chinese girl!”The use of the term “rescue” in Sharon’s narrative is significant as it links to a larger postcolonial critique of Westernization and colonialism as processes that create hierarchies in settings where local populations were seen to be lacking and in need of direction from a more “enlightened” and “whitened” West.Sharon says she does not believe that LDS missionaries or leaders intended to make her feel inferior in any way, but imbibing a gospel message in the British colonial context of Hong Kong (where American neocolonialism was a growing presence) had unintended consequences for her identity formation. She writes:

I think I subconsciously felt inferior and confused about my ethnicity for years. I didn’t consider myself Mainland Chinese because I was born in a British colony and Communist China was seriously looked down on by Hong Kongers. They were the unfortunately patriotic and impoverished hillbillies. Sadly I wasn’t able to find a term to describe my ethnicity other than the unofficial term “Hong Konger” which was not accepted by everyone. . . . Thanks to the Church, I was able to attend BYU-Hawaii. I became somewhat “Americanized” there and I suppose I liked it. And I still am glad that I had that experience. After being away for almost ten years, I moved back with my white American husband and a half-white little daughter. . . . I still cringe when I try to look back at the first ten years that I was back. Now that I’m in my mid-forties, I feel more secure about being a Chinese woman. . . . for the first time in a long time I feel at peace with my identity as a Chinese person. My sense of security comes from being more mature and not trying so hard to be anybody other than myself. I have started to accept my weaknesses and realize that I have probably lived more than half of my life already. I need to stop trying to be someone I’m not and really feel good about being me. By me, I mean me, not just as a Chinese person, a woman or a Mormon. I have issues with all three of those identities.

For me, Sharon’s story is a cautionary tale about the ways in which messages about spiritual and personal success were inflected by American exceptionalism and white privilege during Hong Kong’s late colonial era. Her story reminds me of a Caucasian colleague at the university where I teach, who left the LDS Church after completing his missionary service in Hong Kong. He was deeply frustrated by the white supremacist attitudes he observed among companions and some leaders. He is one of several ex-Latter-day Saints I have met in Asia, who have, thanks to the preparation their LDS missions gave them, found deeply rewarding work and relationships in Asia, but who were unwilling to stay in the Church, in large measure, because of what they saw as its promotion of American exceptionalist rhetoric and US corporate cultural mores.

Sharon has been able to find a way to stay in the fold. She believes that attitudes have changed to a significant extent in recent years both in Salt Lake City and in Hong Kong, and she has become more comfortable negotiating between her past and her present as well as feeling more authentically herself at church. She speaks and writes in good-natured fashion about learning to “un-clutter” her mind by removing the negative messages she received at church about Chinese culture, or the subtle manifestations of white privilege she observed both on her mission and in various LDS congregations on both sides of the Pacific. Still, reading her narrative one notices the multiple legacies of colonialism and neocolonialism (and sub-ethnic tensions within what has come to be known as Greater China) those of us who worship in Hong Kong have inherited. For now, Sharon’s conscious determination to “stop trying to be someone I’m not” means that she has become more comfortable with the disparate strands of her identity. She continues the process of un-cluttering her mind by acknowledging where exceptionalist or ethnocentric rhetoric may still have a subtle but significant impact on herself and her family.

Identity Work and the Asian LDS Diaspora

As Sharon’s story illustrates, there are lessons in transnational and diasporic lives for a church that is, despite hopeful signs of going global, still seen as very American in its approach at times and still very white and male in terms of its most visible leadership. There are, of course, comprehensive training initiatives that reach from Salt Lake City to the grassroots of the Church throughout the world, empowering local leaders to make decisions that best benefit their local congregations. One sees the fruits of that effort in Hong Kong in both “local” and “expatriate” units. Not only is the membership of the Church now several generations deep in the local Cantonese-speaking wards and stakes, but in the Hong Kong China District, the small but growing Mandarin Branch I mentioned earlier is a fascinating site of multiple generations of Chinese sub-ethnic negotiating and community building. Ethnically Taiwanese, Hong Kong Chinese, and Mainland Chinese Latter-day Saints serve with Chinese American and Caucasian members who have served Mandarin-speaking missions. The “Mormon China hands” of an earlier era are still present in this unit and in the district leadership, but they are joined by a younger cohort less conditioned by Cold War values and American exceptionalism and more comfortable with a multipolar world where China is a major player. Many are in cross-cultural marriages or studying and working in institutional settings where crossings and negotiations are happening each day as well as on Sundays.

On the subject of the rise of China and the growth of the LDS Church among those with ties to the Chinese mainland, there is much to be said that is beyond the scope of this paper. (It is difficult to say a lot of it, as Church leaders and PRC government officials have, for different reasons, erected what one friend calls an “electric fence” around China. Church leaders are keen to be respectful of the Chinese government’s strict limitations on organized religion.) There are, however, increasing numbers of PRC-born Latter-day Saints who are baptized outside of China and engage in processes of gathering and grafting as they transit between home and host cultures where they live, work, and attend school. Because Chinese nationals and foreigners are not allowed to worship together in LDS congregations in China, Hong Kong is an important crossroads of religious acculturation for many of these individuals. One woman who is currently a member of the Mandarin Branch was born in the PRC and has lived in both the US and Hong Kong. She speaks of how her identity as an LDS Chinese woman shifts depending on where she is attending church. She jokes about the similarities between institutional hierarchies in Beijing and Salt Lake, and she laments that many of the men she sees serving in positions of leadership in the Church seem to lose their “flavor” [distinct personality] over time. But she acknowledges that it is not easy to try and serve so many different individuals from varied cultural contexts in ways that honor individuality and nurture unity. This same woman has, on a number of occasions, mediated on behalf of Mainland Chinese sisters in her Hong Kong branch with priesthood leadership at various levels, relaying women’s concerns about everything from priesthood leadership styles to food at branch activities.

Because Latter-day Saints who belong to the Asian diaspora cross cultures and continents, they learn to negotiate between familial, governmental, and ecclesiastical worlds on both sides of the Pacific. They exemplify anthropologist Aihwa Ong’s notion of “Flexible Citizenship.” Although Ong wrote about Chinese flexible citizens who transited back and forth across the Pacific in the late twentieth/early twenty-first centuries, establishing multiple “homes” and shoring up security in the face of political and economic turmoil, I see the term as appropriate for those in our district (and elsewhere in the LDS Church) who come to live and work in Hong Kong from all over Asia, as well as those of Asian descent who have lived in North America or other Western nations prior to relocating to Hong Kong. (I hope I am not guilty of reinforcing pernicious model minority stereotyping when I say that living in Hong Kong has alerted me to the burden of representation borne by these flexible citizens. They, as Jessie Embry asserted about Asian Americans years ago, are constantly functioning as cultural bridges.)

Flexible citizenship has historical antecedents that we don’t often acknowledge at church. Although I appreciate messages from the pulpit encouraging all of us to think more about what we have in common than what divides us, I worry at times that our well-intentioned desire to foster unity in our church community breeds a certain historical amnesia, which can dull our sensitivity to the reasons why we aren’t as unified as we might be. We all bear the legacies of our predecessors when we arrive at our meetinghouses each week, and being thoughtful about those legacies as we worship can pave the way for treating each other with more care and respect. As a people, I don’t think that we have begun to appreciate the balancing act that many Latter-day Saints of Asian descent (particularly those who came of age during and shortly after World War II) have performed and continue to perform as they bridge between cultures and countries.

I am cognizant that many of those within the LDS Asian diaspora may not view themselves as doing anything particularly extraordinary as they demonstrate their flexible citizenship. For example, Lily Lew, who has lived in Hong Kong since 1992, is an American-born Chinese woman who grew up in Queens, New York, graduated from Brigham Young University, and is the mother of four children and an active Church member who has served in various leadership capacities. She does as much cultural bridging as anyone I know. Yet she does not consider her negotiations between disparate personalities at church (or in other settings) as a burden. She writes:

So, who exactly am I? I’m actually an amalgamation of different bits of circumstances that have come to form and shape and refine the woman that I am. I am literally a “chop suey” (mixed scraps) of a person. I am American, I am Chinese. I’m a New Yorker living in Hong Kong and a summertime Utah girl. I am a Mormon and I am Confucian. I am a localized expatriate and a tai tai [Chinese term for an economically privileged married woman]. I am a tiger mom, a helicopter parent and a mom that is okay with “whatever.” I have a mother who barely speaks English and children who barely speak Chinese. Some say I am a bridge and maybe I am. I truly feel I not only enjoy the best of both worlds (East and West) but I am comfortable and unapologetic in either world. (Although, some may say I don’t truly belong in their world.) The snapshot of me changes over time depending on the circumstances but the essence of me is I am a woman who is hopefully using the scraps of my experiences to piece together a quilt called life.

Lew, like many flexible LDS citizens I know, cheerfully exhibits a high degree of comfort moving between people, places, and expectations. I would assert, however, that the balancing act is one that requires a significant amount of effort to sustain.

Works in Asian-American and ethnic studies affirm that individuals like Lily and Sharon who engage in multiple crossings and perform as cultural bridges shatter bifurcated notions of race as it has been constructed in the US. When historian Gary Okihiro asks, “Is Yellow Black or White?” he reminds us that some Asian-Americans have been, at times, able to pass as honorary whites in US society (or have been seen—for better or for worse—as smarter or more hard working than any other ethnic group).Yet just as (or more) often they have been grouped in white minds with non-whites and subjected to harmful stereotyping, seen as exotic and inscrutable, as academic or economic threats, or assumed to be submissive and silent.

Yet despite (or perhaps because of) these difficulties, these flexible LDS citizens have strengthened our community in a host of ways by choosing to “see through” the past and exhibit what African-American philosopher and writer W. E. B. DuBois called the gift of “second sight.” They “see” as ethnically other in an institutional culture that has been (and still is in important aspects) predominantly Caucasian and shaped by European American mores, yet they are also fluent in the language and behaviors of that highly Americanized institutional culture. These flexible citizens have a unique relationship to historical events such as nineteenth- and twentieth-century exclusion laws, internment camps during World War II, Cold War anxieties, fear of the “rise” of Japan in the 1980s, and current anxieties about the rise of the “New China.” Even those who have no historical memory of such difficulties themselves are often the children of parents or grandparents who were shaped by them. Like people of African descent in the US, many of these Latter-day Saints live a certain type of “two-ness” in their abilities to see from the margins of a particular community as well as to understand what is happening at the center.

My own introduction to the performance of diasporic second sightedness and the impact of the Asian diaspora on the LDS Church was through the cultural production (books, speeches, articles) of the late and understudied Chieko Okazaki, an early globalizer and counselor in the General Relief Society Presidency in the 1990s. I didn’t appreciate the importance of Okazaki’s life and works until we moved to Hong Kong. As I began to see the ways in which well-meaning but exceptionalist rhetoric manifested itself in Sunday School and Relief Society lessons, or in leadership training meetings in my own congregation (and in my own worldview), I began to appreciate Okazaki’s frank but gracious promptings to move beyond processes of Americanization in the LDS community within and beyond the Wasatch Front. Her clear conceptualization of a gospel culture that superseded national cultures, and her charge (to women particularly) to draw “circles that include rather than exclude” became central to my own negotiations between my past growing up in Utah and my present life in Hong Kong.

Okazaki assumed multiple burdens of representation, modeling how a woman of Japanese-American ancestry could repeatedly confront racism and sexism in the post-World War II US (including in the LDS Church) and shatter stereotypes of the inscrutable and demure Asian female.She graciously but firmly rebuked the ignorance, anxiety, smugness, and shame surrounding sensitive topics ranging from depression and abuse to racism and gender inequality. (When I listen to friends at church comment on how much they appreciate the global vision and inclusive rhetoric of leaders such as Elder Dieter Uchtdorf today, I enthusiastically concur but I can’t help but think that Sister Okazaki was saying the same thing decades ago.) Not only was Okazaki a globalizer as well as a gatherer and grafter, she also gracefully bore a particular burden of representation over several decades, often very publicly. Her steely refusal to ignore the past but rather cheerfully “see through” it and the shadows it cast offered and continues to offer a blueprint for decolonizing Latter-day Saint mindsets and thinking beyond borders of various types; psychological as well as topographical.

Nearly two decades removed from Okazaki’s experiences, Mormon Millennials in Asia are the product of diasporic pasts and the rapid expansion of technology, particularly social media. One example of this cohort is Michaela Forte, an undergraduate majoring in comparative literature at the University of Hong Kong. Michaela (like many of her contemporaries who have grown up in the contact zones of rising Asia) is the second-sighted and bi-cultural product of a Hong Kong Chinese mother and a Caucasian American father. She is, for me, an example of the young LDS women that New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Laurie Goodstein wrote about in early 2014 when they took stock of the LDS Church’s decision to lower the age of missionary service for women and men.While Michaela is excited about her recent mission call to Australia, when she returns from her mission she plans to finish school and pursue an academic career. She wants to balance having a family and a professional life but she has some anxiety about how that will be perceived by others at church. She is a devoted daughter, sibling, and visiting teacher, active in the Young Single Adults program, a branch chorister, and a constant presence at set-up and clean-up time whenever she attends a church event. In short, she is as devout in her actions as she is passionate about her spiritual and educational seeking. She looks for role models in various places, including the Bloggernacle, and she is wondering how she and other women who work so hard at balancing their lives will fare when it is time to marry.

When she finished reading Joanna Brooks’s memoir, The Book of Mormon Girl: A Memoir of an American Faith, Michaela said she appreciated Brooks’s broad-minded perspective but she was keen to find her own place in the conversation. She reflects:

There is no handbook that tells me how to be a good Mormon. There will be no handbook that tells me what I should do and when I should do it. However, perhaps there will be a blog entry or a book of some sort that tells me that there is more than one way to think, that there is more than one way to live this religion. What I want to hear is that we can be worthy temple [recommend] holders without being the cookie cutter Molly Mormons. What I want to hear is that I can return with honor even though I didn’t go to “The Lord’s School” [BYU], even if I dream to pursue a career while raising a family, even if I put my education above all other things in life. Because at least I have given it my best shot.

Michaela’s determination to craft an identity as an LDS woman that allows her to cultivate her intellectual gifts and maintain certain traditions will be a twenty-first-century version of Sharon’s late twentieth-century journey to find greater self-acceptance within LDS society. The challenges today are different and Michaela is using a variety of tools (scriptures, literature, social media and her own agency) to seek inspiration and direction. She is adamant about wanting to use the privilege she has been given to make a difference in others’ lives but she eschews a sense of “chosen-ness,” as that seems to be too closely linked with the lingering strains of American exceptionalism that she has observed, and chafed at, at church. She muses:

Perhaps this difference will only be me becoming a better person; perhaps it is making someone happy or preparing someone for baptism. I do not know. But if I can make a difference (one of my lifelong goals), then I am content and satisfied. At the end of the day, I have come to understand that I cannot control how the Mormon culture has unconsciously influenced or shaped me, yet by recognizing and acknowledging it, I have been given a second chance to decide and choose again, with as much conscious agency as I have and with the gift of the Holy Ghost.

Sister Societies: LDS Foreign Domestic Workers in Hong Kong

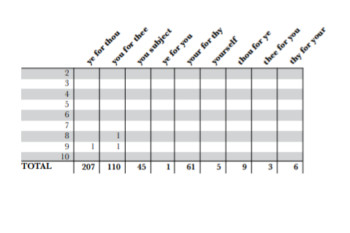

Often, when one thinks of the Asian diaspora in the LDS community, Mormons of Japanese or Chinese descent spring most readily to mind. However, the bulk of the Hong Kong China District is made up of women from the Philippine Islands. This fact makes our district, arguably, the most gender-imbalanced entity of its type in the Church. It is comprised of approximately 1,800 members. About 1,350 are women (including young women) and 1,000 of the women are employed as foreign domestic workers, often referred to as “helpers,” who have “crossed in planes” from the Philippines with a few dozen sisters from Indonesia and a small cohort from Nepal. In the early 1990s, as the International District was created to serve all non-Cantonese-speaking Saints in Hong Kong, domestic workers (many of whom were already meeting in separate units in local stakes) were given the choice to attend “regular family branches” (traditionally expatriate units on both sides of Hong Kong Harbor or in Discovery Bay; the Discovery Bay branch is a fully integrated unit where “helpers” and “expats” worship together although some domestic workers still choose to attend sister units on Hong Kong Island) or one of four “Sunday” units (Island I and II branches meet on Hong Kong Island, Peninsula II meets in Kowloon Tong, and Peninsula III meets in Kwai Fong in the New Territories). A fifth branch, Victoria II, is comprised of five “weekday families” (smaller groups who attend the “Sunday block” meetings Tuesday through Saturday depending on their designated day off). Several years after the organization of the district, domestic workers were strongly encouraged to attend the “helper branches/sister branches” (the terms are not official but have become familiar monikers) where their unique needs could be better met. However, those who choose to remain in regular family units are not, generally, given callings or assigned home and visiting teachers. (More about the strengths and criticisms of these units and the policies that govern them hereafter.)

These special units comprised mostly of women are structured so that the Sabbath is a lively and rewarding but lengthy day of worship and fellowship for Latter-day Saint domestic workers and those who serve them. Sundays include a regular three-hour block of meetings, home and visiting teaching, Relief Society activities, and Family Home Evening. There are several differences between these and other LDS congregations. In addition to the large numbers of females in attendance, there are structural issues to reckon with in order to keep things running smoothly and to provide sisters with opportunities to learn and grow spiritually. With the approval of the area presidency, branch and district leaders seek to uphold official guidelines while adapting to particular circumstances. Women are called and set apart as executive secretaries/administrative assistants (names are often blended and/or used interchangeably), branch mission coordinators (with responsibilities similar to those of branch mission leaders), Sunday school superintendents or coordinators (with assistants rather than counselors and responsibilities similar to those of a Sunday school president/presidency) and as assistant membership clerks. They attend branch council meetings and constitute the bulk of the branch council.

There are other differences including various manifestations of charisma and creativity that are rare or non-existent in the more stereotypically “expatriate” branches. In the sister branches, one is immediately granted acceptance and welcomed to participate in any and all meetings and activities. Testimony meetings are one of many examples of Melissa Inouye’s aforementioned notion of heterogeneity within homogeneity. Women sometimes sing part of their testimonies and share intimate stories of their challenges with homesickness, culture shock, difficult living conditions (many literally sleep in closets or bathrooms, or share beds/bedrooms with young children), long work hours, and heavy caretaking/cooking/cleaning loads overseen by moody, controlling, or verbally (and sometimes physically) abusive employers. Generally speaking, domestic workers in Hong Kong experience social marginalization (they are denied full civil rights under agreements between their home governments and the Hong Kong government), and the pain of going for months or years at a time without visits with spouses, children, or other kin except for regular Skype chats and phone calls.

Occasions for expressions of individual and communal creative energy and pathos in these congregations are valued opportunities for women to step outside of their weekday routines and elevate their sense of self-worth as they worship, steeling themselves for the week ahead. Choir numbers, skits, and dance performances weave gospel principles with joyful recreation in often surprising ways. Visiting teaching conventions and Relief Society anniversaries are serious productions that reflect thoughtful preparation and practice and stunning displays of beauty on a budget. (Decorations, costumes, mementos, and comfort food are important elements of these events.) On these occasions, re-enactments of the Mormon pioneer trek along the North American frontier (complete with actual-scale representations of handcarts, jagged cardboard rocks, and imitation snow squirting out of bubble guns) conclude with comparisons between nineteenth-century American and present-day Asian pioneers, all of whom sacrificed for family and faith.

The importance of these celebratory and inspirational events becomes more apparent when one thinks about the sacrifices the sisters make to prepare and attend them. They are carefully choreographed attempts to balance uplifting messages with Church-approved recreation, given that this is the only day off the sisters will have all week. Generally speaking, when boundaries blur, leaders are kind and good-natured participant observers. (One branch’s recreation of a popular reality television show, “Relief Society Fashion Model,” joyfully presented modest yet stylish clothing for audience approval. It opened with a tribute to past Relief Society presidents and a lively dance to a hip-hop beat.) As a district Relief Society president, my initial desire (and a few early attempts) to “liberate” my Relief Society sisters who are already overburdened with the work of care from doing more stereotypically female domestic work at church quickly morphed into a desire to support and respect the ways in which they used domesticity as a creative outlet and an expression of self-determination. I still struggle to know how to best add value in these settings. My academic training and deep immersion in LDS culture in North America provides me with a certain set of tools to teach, but it has also made me keenly aware of how my own past inserts itself in ways that may limit rather than lift.

What I have learned in my calling, and have appreciated about many of the brethren with whom I work as well as the sisters we serve, is that we are all engaged in learning how to honor individual agency and inspiration as we follow Church protocol. The exercise of agency is evident as sisters come to various conclusions about what business/shopping they do on the Sabbath, how they calculate tithing given the fact that paychecks are often committed to pay debts or support needy family members before being cashed, and how those with children of their own uphold traditional models of LDS motherhood when they are raising other people’s children and trying to long-distance parent their own. Our sisters who are domestic workers are, generally speaking, frequently infantilized or seen as sexual objects in Hong Kong society. As Church leaders we worry about how we can ensure that they feel like they are true equals on the Sabbath when they are anything but during the week. LDS families who employ domestic workers try to level the social asymmetry but even at church it is not uncommon to see expressions of deference in conversation or self-segregation in seating arrangements or in social settings.

And how does history and culture graft onto the patriarchal leadership structure of these special needs branches in Hong Kong, given that there are so few priesthood holders available to serve in these units? The answer is complicated. I have observed that while many of our sister units are, in some respects, an apparent example of Mormonism functioning as a matriarchy, in reality, the few men who are called as leaders in these branches are regarded not just with admiration, but often obsequiousness. Yet they don’t generally take advantage of the esteem and they minister to a dizzying list of temporal and spiritual needs. I have, I confess, seen a few male leaders exert what I consider to be an inordinate amount of power over certain aspects of their members’ lives. Yet more often, I have observed (and many branch presidents confirm) that men who are called to preside in these branches (and their wives who cheerfully serve with them and must struggle to find their place in these special units) have developed a greater ability to trust these women—both their wives and those from a culture different from their own—and they see them as having greater capacities than they had appreciated previously. There is, of course, an asymmetry to the structure that can exacerbate gender imbalance and perpetuate the sorts of colonial mindsets and power structures that still exist in the Philippines and Hong Kong as well as sexist behaviors that are still too common in LDS congregations everywhere. As an LDS feminist I see the work we have yet to do in order to take women seriously as partners in leadership positions given an all-male priesthood structure. Yet there are also unique opportunities for pioneering a model for global Latter-day Sainthood that takes account of the complexities of gender, national, cultural, economic, and political dynamics while forming and nurturing a gospel-centered community.

One helpful academic study that informs my thoughts about our district in Hong Kong is Rhacel Parreñas’s research on children of global migration. Parreñas argues that the outmigration of Filipina mothers may challenge traditional gender norms in the short term but reinforces them over time.I would argue that one observes both resistance to and accommodation for traditional gender roles within the LDS foreign domestic worker community. These sisters are living on their own in somebody else’s residence, working as breadwinners who send their salaries back to husbands and children, but they are, in general, quite conservative in their attitudes towards women’s issues and gender inequality. (I have been cautioned by more than one of them not to be “too radical” in my views about gender roles within the Church.) Yet I do think their performance of flexible citizenship extends to more flexible notions of gender role expression. To that end, more research needs to be done about how LDS families in both the Philippines and Hong Kong are forming various identities as their lives are shaped simultaneously by their religious beliefs, cultural codes, and experiences of migration.

There has been, since the arrival of a critical mass of domestic workers in Hong Kong, an ongoing debate about how to best serve these sisters within the LDS community. Some Church members and leaders worry about a marginalizing effect on them as they are cordoned off in their own units. Beau Lefler, an attorney, university lecturer, and member of the Discovery Bay Branch, where domestic workers are integrated into the small congregation, is one of a small cadre of Latter-day Saints involved in helping to expand civil rights for domestic workers in Hong Kong. He writes:

So why do we place the Domestic Helpers in branches all by themselves? My first impressions are not positive: 1) we don’t really need them for our branches to function (from a pure governance role—not spiritually function, which I realize should be the same but doesn’t have to be), and 2) if women aren’t running families, we don’t really know what to do with them other than to group them together and we put them in charge of each other. We have a whole bunch of Mormon women who are here alone, and we want to do something with them that is helpful. Maybe it’s good to think about the difference between two goals: 1) we want to create a spiritual environment for these women to grow and to support each other, and 2) how are we integrating them into a church based on families if we keep them separate from all the families, while many of them are without their own families?

What is of particular interest to me in this dialogue is that our current district president, Benjamin Tai, who is a Hong Kong born, Western-educated (and highly Americanized) ethnically Chinese man, moves between various groups in this debate—and many others—carefully soliciting diverse opinions, integrating various perspectives, coloring inside the lines of Church guide lines, and expressing confidence that all Church members have the best of intentions as they present their seemingly disparate views. He argues:

In my view, the purpose of church boundaries is not to cause grief, heartache and headache for members or those in leadership callings. I am just very glad that anyone is willing to come and spend 3+ hours of his or her day off with us. My only desire is to make sure that for those that come, we are organized appropriately so that they can get the most out of their time and that spiritual growth is fostered and temporal assistance, where required, can be administered in the best possible way. . . . Your continued thoughts and suggestions are welcomed and requested.

President Tai and other leaders who are “flexible citizens” in their own right, are able to concurrently understand a highly Americanized corporate leadership structure and the local needs of the Church in Hong Kong. Completely fluent in several cultures (Hong Kong, American, and Wasatch Front LDS), Tai demonstrates a high tolerance for individual difference, institutional resistance, and a willingness to ask unconventional questions that are, surprisingly at times, met with a positive response. One example of this ability to navigate in a “glocal” manner is the recent decision to open the Hong Kong Temple once a quarter on Sunday afternoon so that domestic workers who cannot attend during regular hours of operation will not be denied access. While there is an ongoing debate about the best way to draw branch boundaries, there is general agreement on the need to cultivate more culturally and socio-economically sensitive mindsets as the Church in Hong Kong continues to grow, particularly among outmigrant populations from other Asian countries.

The transnational stories of sisters who leave their homes and families in the Philippines to work in Hong Kong are a vital archive that needs to be consulted when understanding the growth of the LDS Church in rising Asia. Likewise, their voices within the Asian diaspora provide evidence of the transition from an American to a global institutional culture. Church leaders struggle to know how to best counsel sisters who, in an institutional framework that favors traditional family norms, simply feel they have no choice but to leave their children in others’ care in order to provide for them.As Marissa Carino Estipona, an LDS domestic worker from the Philippines (a flexible citizen who has worked in Hong Kong, Beijing, and recently immigrated to Canada) writes:

These are very sensitive/tender “things” when it comes to how or when is the best time to make comments/talks or even just a mere questions about all or even about each of them. Maybe because as much as we all wanted to be with our loved ones/families . . . we simply just couldn’t afford it! Meaning . . . we couldn’t bear to see our family go hungry, our children not to go to school etc.

Like many of her compatriots, Marissa has known the sting of separation from her husband and son but she believes she made a difficult but necessary choice. She appreciates LDS friends, Church meetinghouses, and the temple for providing her places of refuge from her difficulties; however, she has been offended by Church members she felt didn’t understand her decision to leave her family. She notes that she was “very lonely” when she worked in Beijing as she was “the only Filipino LDS there at that time.” Without a community of supporting sisters like she had in Hong Kong she says it was inevitable that “most of the members were just in their usual hi’s and hello’s and the rest seemed like I didn’t exist at all!” One sister, she recounted, “instead of saying How are you ? She asked me . . . Is it worth it? (She meant me working as a Domestic Helper and being away from family.) I responded . . . Everything is worth it for my family! That was her way of greeting me?” Marissa’s experience is one of many examples domestic helpers share of their views about well-meaning members who are seen as passing judgment rather than offering support. Marissa generously credited the woman as trying to be helpful but said she felt that perhaps this particular American sister simply hadn’t known the sort of poverty she and most other domestic workers had known. Marissa and many others in similar situations have, for the most part, continued to take comfort in what sustains them at church. They don’t generally expect more privileged members to relate to their situations but they are deeply appreciative of those who reach out to them in various ways. They are, nearly always, endlessly kind to all members they worship with each week, even those they feel are judgmental, and they are confident that the decisions they make are the ones the Lord wants them to make for themselves and their families. Their flexible citizenship in the “nation” of the LDS Church gives them a firm belief in personal revelation and as they exercise their agency, they selectively jettison messages that contradict what they believe to be inspiration.

Conclusion

The contemporary crossings in planes that bring Latter-day Saints to and from Hong Kong translate into varied narratives and personal “pioneer treks” grafting belief onto experience and negotiating between identities, desires, and expectations. The contact zone of the Hong Kong China District is a space between East and West, similar to the spaces that Laurie Maffly-Kipp has written about in her work on transpacific connections in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Then and now, the “brain drains” associated with migration and diaspora have been brain gains for the urban Church in many countries. Crossings were made for evangelism, education, or enterprise, and sometimes more than one at the same time. Twentieth- and twenty-first-century sojourns echoed their nineteenth-century predecessors. Today, the work of “gathering and grafting” helps to “hasten the work” of globalism as well as salvation.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue