Articles/Essays – Volume 46, No. 3

Comparing Mormon and Adventist Growth Patterns in Latin America: The Chilean Case

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

Mormonism, Adventism, and Jehovah’s Witnesses are the three great American religions of the nineteenth century.Although they started out as radical groups led by charismatic prophets, each ultimately followed a different trajectory of opposition and accommodation to U.S. mainstream society.One thing they had in common was their missionary zeal, which was strengthened by the fact that each was certain that it was the only true Christian church on Earth. This missionary zeal led to extensive proselytizing efforts, first in the United States and soon abroad. Adventist and Witness missionaries arrived in Latin American countries in the late 1890s, but Mormonism first had to redefine its core doctrine (the gathering of Zion), before President McKay defined international expansion as a key goal.Consequently, Adventists and Witnesses currently have a far greater proportion of their total world membership living outside the United States than Mormonism.All three churches have experienced, and to some extent are still experiencing, significant membership growth in Latin America. So far, however, no literature explicitly compares the three religions and their growth patterns in Latin America.

This article summarizes the patterns of growth, first of all, for the Latter-day Saints (LDS) and then for the Seventh-day Adventists (SDA). For each denomination, the discussion begins with an overview of growth in Latin America generally, followed by a focus on growth in Chile specifically. Historical developments in religion across Latin America generally provide an important context for understanding the religious scene in any specific location, but every country also has its own unique constellation of internal and external factors influencing the growth of new religions there. Possibly the greatest LDS success story in Latin America, Chile has had a long history of a Roman Catholic religious monopoly, a unique early Pentecostal boom (1930–60), the brutal Pinochet military dictatorship (1973–89), a fragile new democracy since 1990, and a booming macro-economy since 2000. This article offers the case study of Chile to demonstrate the usefulness of country-by-country analyses, especially when employing comparisons of two or more religious denominations.

As indicators of growth, whether in Latin America generally or in Chile particularly, I use year of arrival, the official absolute membership numbers, membership as a percentage of the country’s population, and average annual growth rates for 2006–7. In analyzing membership growth within Chile particularly, I employ a model that distinguishes between factors that are internal and external to the Church and between factors of a religious and non-religious nature. This model is summarized in Figure 1.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1: Analytical Framework for LDS And SDA Church Growth in Latin America, see PDF below, p. 46]

The church growth model analyzes church growth as the result of four religious and four nonreligious factors, which can be both internal and external to the church under study. The internal religious factors are (1a) appeal of the doctrine and (1b) evangelization activities; the internal nonreligious factors are (1c) appeal of the church organization and (1d) natural growth and membership retention. The external religious factors are (2a) dissatisfaction with Catholicism and (2b) responses from the Catholic hierarchy to non-Catholic growth; the external nonreligious factors are (2c) social, economic, and psychological anomieas well as (2d) urbanization, which uproots people and makes them more susceptible to join a new church.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1: Registered LDS Membership in Latin America, Year-End 2007, see PDF below, p. 47]

Mormon Growth in Latin America

The U.S. proportion of global LDS membership halved from 90 percent in 1960 to 45 percent by 2007. The second most important continent for Mormonism in 2007 was Latin America (38 percent), followed at great distance by Asia (7.25 percent), Europe (3.5 percent), Oceania (including Australia and New Zealand; 3.2 percent), and Africa (2 percent).Latin America remains the main growth reservoir for Mormonism. If the current growth rates continue, the majority of Mormons will be Latin Americans by the year 2020.

The Mormon mission in Mexico began in 1876; there were also early missions to Argentina (1925) and Brazil (1928).Paraguay received its first LDS missionaries, coming from Argentina, in 1939. In the 1940s, LDS missionaries arrived in Panama (1941), Costa Rica (1946), Guatemala (1947), El Salvador (1948), and Uruguay (1948). The 1950s witnessed further LDS missionary expansion into Honduras (1952), Nicaragua (1953), Peru (1956), and Chile (1956). A third wave of missionaries took off in the 1960s in Puerto Rico (1964), Bolivia (1964), Ecuador (1965), Colombia (1966), and Venezuela (1966). The LDS mission in the Dominican Republic was the most recent, starting in 1978 (see Table 1).

The result of this gradual LDS missionary expansion into Latin America was a highly uneven growth distribution. The simplest indicator is the LDS membership on record as a percentage of the total population for each country. By this standard, Chile (3.3 percent), Uruguay (2.7 percent), Honduras (1.77 percent), Bolivia (1.61 percent), and Peru (also 1.61 percent) are the most heavily Mormon countries of Latin America, while Brazil (0.55 percent), Venezuela (0.53 percent), Puerto Rico (0.5 percent), and especially Colombia (0.36 percent) are the least Mormon ones (see Table 1).

Another way to analyze the Mormon presence in Latin America is by looking at the average annual membership growth rate for each country, also reported in Table 1. In 2006–7, LDS membership growth stagnated at 1 to 3 percent annually—comparable to population growth—in Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Colombia, and four countries in Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Pan ama).After four decades of expansion, LDS growth in these twelve Latin American countries started to slow down after 2000 for three main reasons. First, most people who might be interested in joining the Church had probably heard the Mormon message by now (“saturation”). Second, the number of missionaries has gone down in some countries. Most importantly, however, “missionaries began to concentrate on reactivation and retention, and the number of baptisms fell.”

However, LDS membership growth in 2006–7 was still strong in a second group of five Latin American countries: the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Brazil, Paraguay, and especially Nicaragua. The average annual growth rates for these five countries ranged from 4 percent in the Dominican Republic to over 8 percent in Nicaragua.To explain why growth persists here would require a country-by-country analysis, along the lines of what I did for Nicaragua.

The typical LDS convert in Latin America is a young (15–25) urban woman of upper lower class or lower middle class origins. S/he is attracted to Mormonism because of its smooth organization radiating success and middle-class values, its strict code of conduct, its practical teachings (e.g., on raising children and household budgeting), LDS doctrines and spirituality, the LDS style of worship and hymns, and its lay priesthood for men. Some new members explicitly reported being dissatisfied with Catholicism.Most people are recruited through their own social networks (LDS friends and relatives) or through the huge missionary force.When asked about main attraction factors, Guatemalan Mormons mentioned the strict code of conduct, learning new things in church, feeling the joy of God’s love, being blessed with miracles, and receiving support from fellow members.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that the official membership statistics only tell part of the story of Mormon growth. LDS retention rates were quite low, hovering at 20 to 30 percent, all over Latin America (and elsewhere.)The aggregate data describe the typical LDS dropout as an urban man of upper lower-class or lower middle-class origins.Studies by the LDS Church show that 80 percent of all inactivity begins in the first two months after baptism.These studies also show that, for some new converts, receiving a calling helped them become quickly integrated into the ward organization, while for others, the pressure to perform in a calling seemed too intense and they dropped out.If the testimony of the new member was (still) relatively weak, if outside pressure from nonmember relatives was strong, or if no good rapport was established with LDS leaders, the new converts would most likely drop out. Other important factors influencing retention were the time and money demands the Church madeand backsliding into alcohol problems.Inactivity was often related to bad experiences with leadersand members, who converts perceived as rarely devoting time to them and often ignoring them entirely.All in all, at least half of all new Mormon members in Latin America became inactive within a year.The percentage of those who become inactive may be even higher: the correlation between the official LDS membership figures on record and self-identified religious affiliation on national censuses was 27 percent in Brazil, 24 percent in Mexico, and only 20 percent in Chile.

Mormon Growth Patterns in Chile

On paper, growth in Chile is Mormonism’s great success story of Latin America. According to official 2007 membership statistics, Chile had the highest LDS population percentage of the entire continent: 3.3 percent (see Table 1)—exceeding even the United States at 1.9 percent.However, the Mormon inactivity rate in Chile is around 80 percent, which is higher than usual in Latin America.The high inactivity rate is reflected in the decreasing number of stakes, which had fallen from a high of 116 in 1999 to seventy-four after 2005.During the same decade, the membership growth rate fell to 1.1, far below that of the SDAs and the lowest ever in the history of the LDS in Chile (Table 5). These were outcomes of a rather surprising intervention from LDS Church headquarters (an unusual example of factor 1b in Figure 1), when Apostle Jeffrey R. Holland was sent to live in Chile during 2002–4 on a special mission to shape up the affairs of the Church there. The drastic reduction in the number of stakes, and in the general growth rate, might be attributable in large part to numerous excommunications of disaffected members and local leaders (according to anecdotal reports). Yet Holland also implemented a number of new policies intended to slow down the baptism rate. For example, he insisted that potential converts attend church at least three successive weeks before baptism, and he began requiring missionaries to spend at least half their time reactivating lapsed members.

The Mormon Church in Chile has a long history. Elder Parley P. Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve spent five months in Chile in 1851–52, but ultimately decided against establishing a permanent LDS mission there. So it was over a century later that the first LDS missionaries from the U.S. arrived in Chile in June 1956. They baptized the first Chilean citizens on November 25, 1956. In October 1959, Chile and Peru became part of the new LDS Andes Mission. The Chilean Mission was finally organized on October 8, 1961.The average annual growth rate from 1960 to 2008 for the LDS Church was an astounding 17.2 percent.

Based on Table 2, we can distinguish five main LDS growth periods in Chile:

Period 1, 1960–71: boom years, AAGR 41.4 %.

Period 2, 1971–76: low growth, AAGR 6.3 %.

Period 3, 1976–85: high growth, AAGR 23.5 %.

Period 4, 1985–90: average growth, AAGR 12.2 %. Period 5, 1990–2008: low growth, AAGR 3.5 %.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2: Registered LDS Membership in Chile, 1956–2008, see PDF below, pp. 52–53]

Period 1, 1960–71: Boom Years. Between 1960 and 1971, the number of members of record increased sharply from 614 to almost 20,000, reflecting an average annual growth rate of over 41 per cent. In these early years, the people who converted to Mormonism in Chile had a particular socioeconomic profile: “Among the early LDS converts, many were members of Chile’s professional and business upper middle classes.”They felt attracted to the novelty of the religious innovation of Mormonism (factor 1a in Figure 1), which appealed especially to people already dissatisfied with Catholicism (2a). The number of LDS missionaries steadily increased and they were much better prepared for their proselytizing (1b).The LDS Church thoroughly revised its worldwide missionary program, requiring missionaries to use six standardized lessons (nowadays called discussions) to teach investigators all over the world the same basic principles of Mormonism.There was more emphasis on the unique elements of Mormon theology and on the rejection of the status quo in other churches (Catholic and Protestant). Meanwhile, urbanization (factor 2d) continued in full swing. The population of Santiago’s urban agglomeration grew from 1.3 million in 1950 to 2.8 million in 1970 and 4.7 million in 1990. By then, Santiago contained one third of the total population of Chile.For the Mormons and the Pentecostals, the new city dwellers formed an easily accessible reservoir for recruitment.It is likely that many converted to Mor monism after being disappointed in Protestantism or Pentecostalism, as happened in Central America in the 1980s.

Period 2, 1971–76: Low Growth. In November 1972, the first stake was organized in Santiago de Chile. Yet the average annual growth rate for 1971–76 was only 6.3 percent, compared to over 41 percent for 1960–71. LDS membership growth was low during the years of the reform-oriented government of Salvador Allende (1970–73) and the first three years after the bloody military coup by General Augusto Pinochet in September 1973. Pentecostal churches boomed during the 1970s, in part because their leaders were all Chileans, whereas in the LDS Church all important leadership positions were occupied by North Americans. A minor economic boom might have decreased the demand for religion, the urban growth rate slowed down, and LDS missionaries were withdrawn for security reasons during the first years of the Pinochet military dictatorship—also affecting growth negatively.

Period 3, 1976–85: High Growth. From 1976 to 1980, the average annual growth rate was an amazing 33.5 percent. The top LDS growth years in Chile were 1976 (40 percent), 1978 (51 percent), and 1979 (30 percent). Chileans were facing a severe economic crisis, rising poverty, an intensification of political violence (the “dirty war” of the armed forces against anyone deemed progressive; factor 2c), political instability, and general turmoil. In 1983, “two important guerrilla groups were formed which would soon begin attacking the Mormons” as representatives of U.S. imperialism.Meanwhile, more Chileans than ever before came into contact with the LDS Church. The full-time LDS missionary force had increased enormously to about 300 in 1985. They were well-prepared, well-organized, and guided by efficient U.S. mission presidents. A great many investigators were baptized within two to six weeks after their first meeting with the missionaries. Competition for members with (charismatic) Catholicism and Pentecostalism was very intense in this period. However, Pentecostal growth had begun to slow before the LDS Church experienced its membership boom in 1976–80.Other significant growth factors were the impact of growth momentumand the global economic cri sis that intensified in the early 1980s.

Period 4, 1985–90: Average Growth. From 1985 to 1990, the average annual growth rate was a little lower than the 1960–2008 average: 12.2 percent. What was the profile of LDS converts in Chile in the 1980s? Rodolfo Acevedo conducted a survey among 700 male converts aged eighteen and older. Almost half (45 percent) “came from the ranks of laborers and unemployed.” But David C. Knowlton found it “equally significant that 15 percent are professionals and 26 percent petite bourgeoisie.”These Chileans were facing the final years of the Pinochet regime, a severe economic crisis, and rising poverty. Meanwhile the fulltime LDS missionary force kept growing, but at a slower pace. Competition for members with Catholicism and Pentecostalism remained intense in the late 1980s. After losing a popular plebiscite, General Pinochet finally allowed democracy to return in 1989, when Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin won the first free elections in almost twenty years on December 14.

Period 5, 1990–2008: Low Growth. After the 1980s, growth rates decreased sharply and rapidly. The average annual growth rate for the entire 1990–2008 period was 3.5 percent: a little higher than population growth, but not representing a sizeable net expansion in membership. What happened? The LDS missionary effort had only expanded. This again suggests that the missionary force does not determine LDS growth.One can think of other factors that are relevant as well. Membership growth in the Pentecostal churches also stalled after 1990. The reservoir of dissatisfied Catholics was probably running empty by now. The Chilean economy was recovering strongly from the earlier economic cri sis. Democracy in Chile was gradually strengthened and political stability steadily improved.

Why did Chileans turn specifically to Mormonism instead of Pentecostalism or (charismatic) Catholicism? Chileans had converted massively to Pentecostalism in 1930–60, and to counter these defections, the Catholic Charismatic Renewal was eventually sanctioned by the Catholic hierarchy (factor 2b), growing strongly in the 1970s and 1980s.I mentioned earlier that Guatemalans were attracted to Mormonism for six main factors: its organization and lay priesthood, its style of worship, being blessed with miracles, its strict code of conduct, its practical teachings, and receiving support from fellow members. The last four factors are not unique to Mormonism: Pentecostalism and Adventism (and the Catholic Charismatic Renewal) also stress a strict code of conduct, practical teachings, miracles, and support from members.

We need to study in-depth through ethnographic methods how and why the two uniquely Mormon attraction factors work for people in Latin America (factors 1a and 1c). What are the unique features of the LDS organization and its lay priesthood? What specific miracles and blessings do active Mormons report? How do the strong ties of the LDS Church to the United States affect its growth? And how do Mormons receive concrete support from their fellow Mormons? When new members do not receive the support they need, many drop out, which helps explain the low LDS retention rates all over Latin America.

Seventh-day Adventist Growth in Latin America

The Seventh-day Adventist Church, organized in 1863, traces its origin to the “Great Disappointment” of 1844, when Jesus Christ did not return to Earth as was predicted by William Miller. Ronald Lawson argues that until the beginning of the twentieth century, and possibly until World War II, “Adventism was highly sectarian and in considerable tension with its [American] environment,” especially in its observance of Saturday, its expectation of the imminent return of Christ, its diet restrictions (vegetarian ism, no alcohol, coffee, or tea), prohibitions on dancing, theater and gambling, and refusal to take up arms. Its view of itself as the one true church and of other groups as apostate “tended to create bitter, mutually held, antagonisms.”

However, the level of tension between Adventists and American mainstream society lowered sharply after the Second World War. Lawson concluded that “the growth and accreditation of their educational and medical institutions has required participation in society and provided opportunities for upward [social] mobility; the five-day work week removed many of the major problems surrounding Sabbath observance; and Adventist dietary and smoking prohibitions have won increasing credibility as a result of medical research.”

SDA leaders after World War II consciously sought to decrease tension with mainstream society, eventually leading to a “marked relaxation of tension with governments, other churches, and societies” all over the world—including Latin America.Lawson concluded that “Seventh-Day Adventists have shown considerable willingness to compromise their positions whenever external threat or opportunities to gain acceptance have made this auspicious. . . . These flowed from their experience of upward social mobility, which led them to relax the urgency of their apocalyptic[ism] and to claim an increasing stake in society.”

The international expansion of the SDA Church started in the late nineteenth century and continued into the early twentieth century. Growth in Latin America first exploded in the 1960s and later again in the 1980s.As a result of this growth, the U.S. proportion of global SDA membership decreased from 26.7 percent in 1960 to 6.4 percent by 2007.The present-day Seventh-day Adventist Church can properly be called an international church, because 94 percent of its worldwide membership was concentrated outside the United States in 2007. It could also be called a Third World church, as 91.8 percent of its global membership was located in less-developed countries. The most important landmass for Seventh-day Adventism in early 2008 was Latin America and the Caribbean (34.7 percent), closely followed by Africa (30.7 per cent) and Asia (19.44 percent), and at a much greater distance by the United States (6.4 percent), Oceania (including Australia and New Zealand: 2.55 percent) and Europe (1.8 percent).

Together with Africa, Latin America is the main membership growth area for Adventism. The contribution of Latin American countries to the worldwide membership increased from 20.3 per cent in 1960 to 34.7 percent in 2008, while the U.S. membership proportion declined from 26.7 percent in 1960 to 6.4 percent by 2007.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church has already been present in most Latin American countries for at least a century now, al though the earliest SDA missionaries arrived in Honduras (1887), Argentina (1890), Uruguay (1892), Nicaragua (1892), Mexico (1893), Brazil (1893), Chile (1894), Panama (1897), Bolivia (1897), and Peru (1898). The earliest SDA mission in Latin America officially opened in Argentina in 1894.In the early twentieth century, Adventist missionaries started working in Paraguay (1900), Puerto Rico (1901), Costa Rica (1903), Ecuador (1904), Venezuela (1907), and Guatemala (1908). A third wave of SDA missionaries took off in the 1920s in Colombia, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic (see Table 3).

The result of this early gradual SDA missionary expansion into Latin America was a highly uneven growth distribution. The simplest indicator is to look at the officially registered SDA membership as a percentage of the total population for each country. By this standard, Peru (2.76 percent), Honduras (2.67 percent), the Dominican Republic (2.58 percent), El Salvador (2.46 percent), Panama (2.44 percent), and Bolivia (2.02 per cent) are the most heavily Adventist countries of Latin America, while Mexico (0.56 percent), Ecuador (0.55 percent), Colombia (0.54 percent), Argentina (0.25 percent), Paraguay (0.22 per cent), and especially Uruguay (0.21 percent) are the least Adventist ones (see Table 3).

Another way to analyze the Seventh-day Adventist presence in Latin America is by looking at the most recent SDA annual membership growth rate for each country, which is also reported in Table 3. After four decades of (high) growth, SDA growth in Latin America seems to be slowing down in only a few countries. An actual SDA membership decrease occurred in four countries in 2006–07: Peru (-0.21 percent), Uruguay (-0.96 percent), Chile (-2.68 percent), and Brazil (-3.66 percent). SDA membership growth stagnated at 1 to 3 percent annually—comparable to population growth—in two countries: Costa Rica (1.74 percent) and Puerto Rico (2.57 percent).

However, SDA membership growth in 2006–7 was still going strong in the third and largest group of Latin American countries: Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, Panama, Guatemala, Bolivia, Honduras, Ecuador, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and especially El Salvador. The average annual growth rates for these thirteen countries ranged from almost 4 percent in Mexico to almost 14 percent in El Salvador.All six Central American countries are represented in this group.

For 2006, the SDA Church reported a general worldwide retention rate of 76 percent in the first year of membership.In the United States, 73 percent of Americans raised as Adventists remained in that church as adults in 2001; by 2008 this percentage had decreased to 60 percent.No information is available for SDA retention rates in Latin America countries.

Seventh-day Adventist Growth Patterns in Chile

The Seventh-day Adventist church arrived in Chile in 1901 and formally organized its mission work there in the late 1920s. Adventism in Chile has been only moderately successful in terms of membership growth. According to the membership on record, about 0.74 percent of the Chilean population had been baptized into the SDA Church in 2007, which is slightly under the Latin American average of 0.87 percent (see Table 3).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 3: Registered SDA Membership in Latin America, Year-End 2007, see PDF below, p. 60]

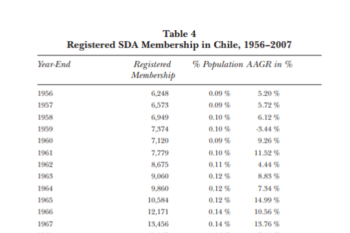

SDA Growth Periods in Chile. Based on Table 4, we can distinguish six main SDA growth periods in Chile:

Period 1, 1956–60: low growth, AAGR 3.4%.

Period 2, 1960–68: high growth, AAGR 10.1%.

Period 3, 1968–73: average growth, AAGR 5.7%.

Period 4, 1973–80: high growth, AAGR 9.1%.

Period 5, 1980–90: average growth, AAGR 6.3%.

Period 6, 1990–2007: low growth, AAGR 3.6%.

SDA membership growth in Chile was remarkably constant, registering an average annual growth rate for the entire 1956– 2007 period of 6.1 percent. SDA growth was low from 1956 to 1960 and again after 1990. The high SDA growth periods were 1960–68 and 1973–80. By 2003, there were 490 SDA churches in Chile with a combined membership of 111,759.In 2007, Adventist membership in Chile stood at 123,412 (see Table 4).

Early Adventism in Chile. The new 1871 constitution in Chile recognized secular marriage, abolished church courts, and declared freedom of worship for the first time in Chilean history.As political stability increased, early industrialization took off and fostered urbanization and the formation of a worker class. The first Adventist canvassers from the United States, F. W. Bishop and T. H. Davis, arrived in Chile in October 1894: “To their disadvantage, neither spoke Spanish. Their sales were meager at first, enabling them only to eke out a living, but they hung on.”The first ordained Adventist minister, G. H. Baber, arrived in Valparaiso in July 1895, supervising the modest growth in the number of SDA converts.Greenleaf wrote: “By 1904 membership was still fewer than 200, sprinkled from Iquique in the north to Temuco and Concepción in the south. . . . Workers were few and added to their burdens was the responsibility of promoting Adventism in Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.”The first Adventist school in Chile opened its doors in April 1906.Chile became a separate conference in 1907.“By 1930, the conference had 29 churches and over 1,700 members and was operating eight schools. A hospital opened in 1958 and a secondary school in 1963.”The stage was set.

Adventist Growth after 1960. All over the world, in the 1960s and 1970s, “Adventists sought liberties (freedom to evangelize, freedom to observe the Sabbath, protection of their institutions) and favors (for example, accreditation of schools, facilitation of pro jects through duty-free import of equipment) and, in return, were willing to help legitimate or otherwise assist regimes. Such relationships were especially numerous among the military regimes of Latin America. For example, in Pinochet’s Chile, “Adventists were known as friends of the president, providing him with legitimation from a religious source when he was under attack from the Catholic Cardinal for torture and disappearances.”This rapprochement with the military regime did not have negative consequences for Adventist growth in Chile in the 1980s, although it may have become a factor in the slowing down of SDA membership growth after the return to civilian democracy in 1990. The average annual SDA membership growth fluctuated between a high of 10 percent in 1960–68 to 5.7 percent in 1968–73, 9.1 percent in 1973–90, 6.3 percent in the 1980s, and a low of 3.6 percent after 1990.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 4: Registered SDA Membership in Chile, 1956–2007, see PDF below, pp. 62–63]

The 1960s Adventist boom period in Chile obviously cannot be explained by its novelty, since the church had already been present for over sixty-five years. Urbanization (2d), early industrialization, growth momentum, and sociopolitical upheaval (2c) all coincided and combined with dissatisfaction with Catholicism (2a). After the 1973 oil crisis led to an economic crisis and a sharp rise in poverty, SDA growth rates went up again in the 1970s. After the end of the Pinochet military dictatorship and the return to democracy in 1990, SDA growth went down sharply to 3.6 per cent per year.

Conclusion

Seventh-day Adventism expanded internationally half a century before Mormonism and can now properly be called a Third World church, whereas Mormonism is (still) predominantly a U.S. church.Adventism currently has a much stronger presence in Africa (31 percent of its global membership) and Latin America (35 percent) than Mormonism (with only 2 percent in Africa and 38 percent in Latin America). Adventism is still growing strongly in thirteen Latin American countries, but SDA membership growth stagnated in Costa Rica and Puerto Rico and decreased in Peru, Uruguay, and Chile. Mormon growth peaked in the 1980s but is nowadays high in only five countries: the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Brazil, Paraguay, and Nicaragua. The 2006–7 LDS growth rate was barely 1 percent in Chile or less than population growth. The average growth rate for the Adventists in Chile that same year was minus 2.7 percent.

Since the early twentieth century, Chile was a representative democracy. This was abruptly ended by the violent 1973 military coup against the reform-oriented government of President Allende. General Pinochet headed a highly repressive military regime, waging a “dirty war” against anybody deemed leftist from 1973 until 1989. The main Pentecostal boom periods in Chile were 1909–15 and 1930–60, with modest growth in the 1970s. As a result, Chile had a Protestant population proportion of about 15 percent in 2002,making it one of the most Protestant countries of Latin America.

Table 5 juxtaposes the LDS and SDA growth periods in Chile and reveals interesting trends. How to explain the low SDA and LDS growth in Chile after 1990? Cragun and Lawson suggest a strong possible explanation for non-Catholic growth stagnation with their theory of the “secular transition.” Using aggregate data for nearly every country around the world, Cragun and Lawson showed that Mormon, Witness, and Adventist growth eventually slows down due to saturation (factor 1d) and reduced demand for religion. Reduced demand typically happens when countries reach a “high level of economic development,” as evidenced by a United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.8 or higher.After that point is reached, all three religions eventually experience very little to no growth.Chile was number forty four on the world list with a “very high” HDI of 0.805 in 2011. The Chilean economy is strong since the 1990s, creating many new jobs and pushing poverty levels down. Chile now has one of the highest per-capita incomes of Latin America and follows the secular transition theory perfectly: All non-Catholic churches have experienced growth stagnation since the 1990s. The LDS Church in Latin America is currently growing, especially in countries with a Human Development Index under 0.8, such as Nicaragua, Honduras, Paraguay, and the Dominican Republic (see Table 1).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 5: Comparing LDS and SDA Growth Periods in Chile, 1956–2007, see PDF below, p. 66]

The similarities in growth patterns for both Mormons and Adventists in Chile before and after 1990 could be seen as a confirmation of modernization theory and deprivation theory. Deprivation theory assumes that people will turn more to religion when they face stress and political persecution or when coping with poverty and economic uncertainty (factor 2c).In the period of early industrialization and high urbanization (2d), the 1950s and 1960s, both Mormons and Adventists grew strongly all over Latin America. After the 1973 oil crisis, Mormon growth in Chile first went down and then exploded, while Adventist growth remained high until 1980. SDA growth in Chile continued at a moderate rate afterward, while Mormon growth peaked in 1976– 85. The main factor here was the growth of the fulltime LDS missionary force (1b), which is an important factor to explain LDS expansion in Latin America.Mormon growth periods in Central America occurred about a decade after the Pentecostal boom, whereas in Paraguay and Chile, Mormon and Pentecostal booms neatly coincided in the 1980s.Adventist growth in Chile likewise coincided with Pentecostal membership expansion in the 1960s and 1970s. LDS missionaries after 1999 focused more on retention than on recruitment (factor 1d), which contributed to the lower Mormon growth rates all over Latin America in recent years. Mormonism has retention rates of only 20 to 30 percent in Latin America, whereas Adventism has a global retention rate of 76 percentand U.S. retention rates of 60 to 73 percent.What accounts for this huge difference? Further study of these and other differences is required to better analyze and understand both the differences and the similarities between LDS and SDA growth patterns—whether in Latin America or elsewhere.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue