Articles/Essays – Volume 44, No. 3

Charles Taylor: Catholic Mentor to the Mormon Scholar

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

I’m going to try and convey aspects of Charles Taylor’s work that I find tremendously helpful in working through the challenges that all of us confront and that give rise to conferences like this one. Let me begin, however, with a personal note about Taylor. He is perhaps the most successful contemporary philosopher bridging the analytic continental divide and is best known for his contributions to political philosophy, moral philosophy, philosophy of social science, and the history of philosophy. One mark of his significance is the contemporary influence of his work on non-philosophers, which stems in part from his encyclopedic grasp of intellectual history and the ease with which he synthesizes history, theology, anthropology, sociology and economics in order and display philosophical insights.For numerous reasons, he has been a very important professional model for me. More importantly, Taylor has successfully negotiated the worlds of faith and reason, opening up a way for me to follow. I do not exaggerate when I say that he has stood as something of a Savior on Mount Zion for me.

If nothing else, I am hopeful that I can convince some of you of the value of reading Taylor’s works as you personally negotiate your way between worlds. I will focus primarily on Taylor’s discussion of the nature of human beings and their meaningful worlds. In closing, I will briefly allude to how Taylor’s work can help Mor mons situate and articulate their religious experience within the broader context of cultural evolution in the West.

The Worlds We Live In

Toward this first point then, I’m convinced that the greatest difficulty facing Mormon academics today is not their ability to contribute to, or earn the respect of, the academic community. Rather, it’s negotiating their departure from a familiar world and their initiation into a new, robust, usually beneficial, and occasionally hostile or at least foreign world—a world in which the claims and practices of Mormonism are, at best, odd and superfluous. To elaborate, I need to discuss what I mean by “world.”

“World” is an important term of art, introduced by Martin Heidegger and used by phenomenologists (like Charles Taylor) ever since.Worlds are the meaningful horizon within which we all necessarily, inextricably dwell. Colloquially, we speak of the world of academia, the wide world of sports, or the world of the ancient Egyptians. These examples help us to get at the relevant phenomenon. Worlds are the holistic background and meaningful context by which each of us makes sense of and copes with the interrelated web of things, actions, people, and purposes of our lives. Worlds shape the way we experience, feel, and reflect. Any object or event we encounter is going to be practically and conceptually related in a holistic way to the other objects and events with which we’re familiar and with which we cope in our practical dealings. It is on account of the position within these practical and conceptual webs that any given thing (i.e., any phenomenon on which we might focus) is able to show up as what it is. For example, I understand lecterns like this one by practically relating it to the other objects with which I cope (chairs, tables, classrooms), and within certain contexts of activity (attending classes, teaching classes, gathering for academic conferences), all of which relate to the purposes and roles that I’ve adopted in my life (perhaps that of a young Mormon scholar).

My example object here—this lectern—is understood by or is meaningful to me on account of how it is embedded within these interrelated, holistic contexts. The same will be true for any object, activity, relationship, or role. The meaningfulness of any particular thing requires its being situated against the holistic backdrop of one’s world. Thus, it is the world of baseball that allows a 90 mph projectile to simply show up as a pitch. Essential to what it is to be a human is our ability to concernfully—that is, passionately and committedly—dwell within such a world. As philosopher John Haugeland recently stated, “It matters to us what happens in the world, it matters to us what happens to us, it matters to us what happens to our friends. …Those are things to build a life on, that one can summarize in the phrase ‘giving a damn.’ . . . In a word, what [artificial intelligence] has so far failed to come up with. . . . The trouble with computers is that they just don’t give a damn.”It may be helpful to note that, while a robot can sense or launch a 90 mph projectile, a robot cannot throw a pitch.

Closed World Structures

Two important elements of a world are one’s (perhaps implicit) intellectual assumptions and one’s moral outlook. These elements work together and help to give structure to one’s world, which in turn serves as “an underlying picture which is only partly consciously entertained, but which controls the way people think, argue, infer, and make sense of things.”As noted, one’s world or the elements structuring one’s world both allow something to show up as what it is (e.g., a projectile to show up as a pitch), and likewise prohibit other things from showing up (e.g., in the world of baseball spectators can’t show up as legitimate outfielders). Thus, Taylor talks about “closed world structures,” which are the correlative intellectual assumptions and moral outlooks that do not allow for (or at least make very difficult) the possibility of experiencing transcendence.

I think it is, first of all, helpful to recognize the fact that whether one has transcendent experiences is largely a function of one’s background world—a world we are largely socialized into rather than a world of our volitional making. Second, Taylor points out that, on their own, the intellectual claims operative in closed world structures are dramatically unconvincing. Despite the way the story gets told, it is the correlative moral outlook or ethic that is always the more significant factor in closing us off to transcendence. We’re converted to the moral outlook and subsequently accept the correlative intellectual claims. I will discuss one example here and give another in Table 1 to help illustrate this point.

One of today’s familiar closed world structures grounds itself in the intellectual claims of an influential modern epistemology. According to this epistemology, what it is to be human is to be a rational, knowing agent set in opposition to an external world of objects. Knowledge itself is a mental representation of that external world. This sets up a hierarchy of certainty in the types of knowledge we are able to possess: I know my own thoughts most certainly (right now I think I’m giving a presentation); less certain are the external and value-neutral objects represented to me (like these gold cuff links); significantly less certain are values imposed on those value-neutral objects (like the preciousness of these cuff links); and least certain of all, if it’s even possible, is any theoretic knowledge I have of the transcendent. (For example, I might infer from the beautiful world I see that there is a beneficent God; knowledge of transcendent things is thus merely inferential, making it epistemologically suspect.)

This influential epistemological picture came under heavy fire in the twentieth century and is now at best a beleaguered alternative. What Taylor finds significant is not the philosophically shaky merit of these epistemological claims, but the fact that, to their proponents, these claims were simply obvious—resulting from stripping away all the smoke and mirrors and scientifically looking at what was left when one examined what we naturally are and experience as humans. According to Taylor, however, there was a powerful ethic at work behind this picture that made it appear obvious and natural—the ethic of the Enlightenment which posited the ideal image of human beings as that of independent, disengaged subjects, capable of reflexively controlling their own thought processes and who insist on self-responsibility. All of these characteristics and behaviors require courage, a refusal of the easy comforts or consolations of an enchanted world; it also allows one to surrender to the promptings of the senses and licenses the dismissal of other forms of coming to an understanding.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1: Modern Epistemology and Materialism, see PDF below, p. 98]

On the one hand, the epistemological picture of this closed world structure is clearly inadequate and is embarrassing grounds for claiming the impossibility of transcendence. This inadequacy doesn’t argue in favor of God, however; and everything in Taylor’s analysis of the arbitrary and weak nature of closed world structures is perfectly compatible with an atheistic universe. On the other hand, the Enlightenment ethic informing this epistemology—independence, control, responsibility, courage, and maturity—is very appealing. Taken as a package and socialized into a world with this background understanding, this intellectual and moral structure can operate very successfully to close off transcendence.

Challenge of the Mormon Scholar

This phenomenon—i.e., the potency of the various structures ascendant in academia—is the real challenge of the Mormon scholar. I simply can’t take seriously the notion that we struggle to contribute to the scholarship of our fields. And I have yet to find a substantive challenge to faith in Mormonism posed by theories in philosophy, religion, history, or the like—which is not to say that I haven’t met individuals who genuinely felt intellectually compelled to abandon their faith. Rather, it’s our baptism into the various closed world structures operative in the world of academia that we find challenging and which, often gradually and unconsciously, convert some of us out of Mormonism.

An important challenge that most of us face is that, while growing up, we’re decidedly not exposed to religious scholarship. The few scraps we do receive come from CES instructors or manuals whose goal and practice are clearly a devotional approach, generally at the expense of a more comprehensive approach. Not yet capable of recognizing the difference, we commonly conflate devotional for academic exegesis, entirely failing to grasp the overall paucity of our religious understanding. This paucity becomes conspicuous and problematic in college and graduate school where we dedicate years of our lives to rigorously developing our intellectual and other capacities within the discipline of our field, often while allowing our spiritual understanding to stagnate. Our experience in the merely devotional settings of the church—Sunday School, Institute, Deseret Book—can be jarring in the wake of a growing juxtaposition of rigor between our academic and devotional lives, particularly when our academic experience (understandably) ignores the spiritual. In Church settings, we often receive encouragement and hear testimonials concerning the efficacy of daily scripture study as a means of shoring up weakening faith. Daily devotional study, however, fails as a strategy to directly respond to a challenge that grows out of an intellectual disparity.

The problem faced is not a lack of contact with the scriptures, but one of the changed ways that the scriptures disclose themselves to us when the depth of our religious understanding does not grow in tandem with our intellectual life and when our approach to scripture and religion more generally remains artificially narrow. If we hold on to a childish, perhaps even a cartoonish spiritual ethic or understanding of Mormonism—one that implicitly compartmentalizes and consequently puts aspects of our life in tension—and if our personal religious experience remains superficial, then following the Sunday School admonition to daily read the Book of Mormon is only going to force us to daily confront how silly and immature our faith appears to us. It is emphatically not simply a matter of daily feeding our spirit as well as our intellect—a strategy that rests on the sandy foundation of a false dichotomy, one that denies Joseph Smith’s merging of the spiritual and intellectual.

The reality is that we are always, in conjunction with those around us, in the process of constructing the world in which we dwell and, consequently, the way in which transcendent experiences do or do not appear to us. It is easy under certain conditions to come to see the faith of our childhood as fundamentally childish. In discussing examples of those who began life with a strong faith but who later felt intellectually compelled to abandon it, Taylor says, “What happened here was not that a moral outlook [e.g., faith] bowed to brute facts. Rather it gave way to another moral outlook; another model of what was higher triumphed. . . . One’s childhood faith had perhaps in many respects remained childish; it was all too easy to come to see it as essentially and constitutionally so.”This result is particularly true when many of our close associates claim childish fantasy as the root of religion. In other words, we experience an understandable colonization of one world by another, resulting in a painful closing off of transcendence. This was my own experience as I went directly from career ambitions in the Church Education System to graduate school.

A Few Possibilities for the Mormon Scholar

Recognizing the reality of the different and competing worlds— not just models or theories—in which we dwell as Mormon scholars opens up several possibilities for how we might operate. First, the proliferation of worlds that flourish and overlap in our pluralistic society opens up the possibility of simply remaining aloof, of maneuvering between our Mormon and academic worlds without ever firmly settling in one or the other. This is a common stance I think, one that offers a sort of therapeutic refuge for some of us as we develop. But I find this approach ultimately unsatisfying and its inherent instability difficult to maintain.

Next is the possibility of learning to dwell within one’s “Mormon” (or other religious) world but changing the shape and structure of that world to incorporate the goods of our academic lives. This is, in my opinion, what the gospel calls us to do. We can recognize that which is lovely, virtuous, and praiseworthy in the very best of our various disciplines of study—including their methodologies, forms of argument, and the contextual value of their insisted-upon impersonal, universal, and wholly immanent explanations. We can humbly recognize the provincial limits of the Church as an institution and the silence of the gospel on many or most of the matters to which we devote our professional time and attention. At the same time, we can recognize the limits, the unjustified grounding, and historical contingency of the closed nature of today’s academic world. Doing so requires the hard-won virtues of humility, rigor, and a thick skin. The humility and rigor go together to shore up the weaknesses in one’s religious assumptions without being drawn in by unjustified epistemological assumptions that work to close off our experience of transcendence.

The greatest difficulty is, of course, the lack of friends with whom to build and share our remodeled Mormon world. I’m an advocate of this second possibility, but I’m skeptical whether we can, while working in academia, ever fully overcome the constant pressure to adopt the mainstream pairing of an intellectual and ethical background that serves to structure the ascendant world of our peers. I’ve been fortunate enough to have peers at Georgetown who have never reacted with anything stronger than mild befuddlement when they see me embracing the same philosophical goods that they do while maintaining the goods of my faith. I know that not everyone is so lucky. Nevertheless, there is undoubtedly a significant alienation resulting from this position.

Being faithfully grounded while openly embracing one’s intellectual education can cause alienation from one’s professional peers; but this position is made even more difficult by the skepticism, prejudice, and hostility that can come from other Mormons. Aristotle was simply right that good friends are necessary for full flourishing,and the religious alienation one can experience (from spouse, parents, in-laws, ward family, etc.) is, I think the most severe challenge in adopting this position. Nevertheless, recognizing the social and ethical nature of these challenges (i.e., recognizing that intellectual honesty does not lead us one way or the other) relieves the overwhelming pressure we sometimes feel to choose between our education and our faith, and opens the door to authentically combining both. Consequently, I believe the social community we’re developing at conferences like this one are far more important to our reconciling faith and knowledge than the propositional content of our presentations. Friends are needed—not just to comfort the Mormon academic, but to actually construct the Mormon academic world I’m advocating.

Finally, I want to address why I describe this second option as dwelling in the Mormon world while incorporating the goods of our academic world, rather than calling it a hybrid world, and why I advocate this position as opposed to its opposite—i.e., dwelling in the academic world while incorporating aspects of the Mormon. This latter is certainly a possibility, and there are models for it that one can follow. I believe, however, that there is a basic asymmetry between the two. I’ve tried to be candid about the genuine difficulties, the cross-pressures, and dual alienation that lie in wait for Mormon academics. Nonetheless, outside of these difficulties for Mormons, I do not see any of the goods of the academic world that are denied a Mormon who remains faithfully grounded.

I believe that Mormon academics have available to them, at least in principle, the goods of both their first and second estate. From within the reverse position, however, that of the secular Mormon, one abandons (or perhaps embraces a denial of) the possibility of transcendence. A secular Mormon can maintain certain cultural goods from his or her Mormon world; but in accepting the cultural background of an academic world as primary, the secular Mormon’s experience of the world inevitably changes so as to preclude the possibility of transcendence. While I’m convinced of this inevitability on an intellectual level, it is my best friend—an atheist orthodox Jew—who has convinced me on a personal level.

Situating Mormon Notions of the Sacred

In concluding, I want to mention how Taylor’s elaboration on the phenomenon of worldhood has deepened my own understanding of Mormonism, and how it demonstrates a successful means of carrying out Mormon studies. In his A Secular Age (esp. 29–54), Taylor performs a sort of philosophical anthropology, discussing two important and related shifts that took place gradually in the development of “Western” culture, and which are key markers of modernity: shifts in how we understand our self and the causal nature of the universe. First, he describes a shift in the nature of our self-understanding, from that of a porous to a buffered self. A porous self makes no inner/outer mental distinction. Instead, we are fully open to what we might call today an external, mental influence for good or ill, protection or attack. The meanings of things are not merely in the human mind, but inhere in things themselves. Our understanding is open to being influenced or impressed by these meanings. Immaterial ghosts are thus physically threatening, as Horatio tries desperately to convince Hamlet atop the battlements of Elsinore.

In contradistinction is the buffered self, for whom the inner/outer mental distinction is quite real. All non-physical aspects of human life (e.g., meanings, emotions, moral values, etc.) are reduced to the merely “mental.” Thus “sticks and stones can break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” And consequently, we scoff at the Horatios and tell our terrified children that a ghost can do no more than scare them.

Paralleling this shift in self-understanding is a shift in our understanding of the way in which things potently interact, from multiple notions of interaction to our modern notion of a merely mechanistic universe of causal interaction. Medieval Europe maintained an understanding of potent interaction through what Taylor calls “influence.” Objects, places, or times can be charged with a positive force whose influence on their surrounding environment is equal to their meaning or value. Thus, holy relics, places, or times can influence, not through mechanistic interaction, but through the openness of our porous selves to their potency.

Alongside influence, our familiar modern notion of causal interaction gradually developed and eventually came to dominate our general understanding. As opposed to influence, causal impingement is mechanistic interaction according to scientific laws that in no way depend on the meaning or value of the objects involved. Hence, any change in one’s well-being in the wake of contact with a relic is understood simply as placebo.

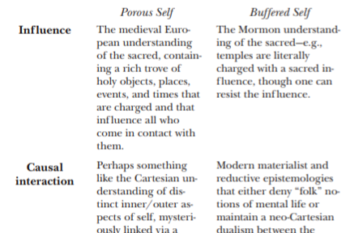

These shifts are directly related to worlds, in that one’s (perhaps implicit) self-understanding and notions of causal relations between objects help to structure one’s world. Consequently, these understandings help shape one’s experience of the sacred (or lack thereof). Taylor focuses on the medieval pairing of porous selves and influence versus the modern pairing of buffered selves and mechanistic causality. Nevertheless, his work in historically tracing these changing notions over the past five hundred years creates a framework containing other possibilities and is fruitful for situating Mormon notions of the sacred.

By and large, I believe that Mormons have adopted a version of the modern understanding of the buffered self, while maintaining a dualistic notion of interaction. Consequently, temples are seen as literally sacred, charged with a pervading influence such that “all people who shall enter upon the threshold of the Lord’s house may feel . . . constrained to acknowledge that thou hast sanctified it, and that it is . . . a place of holiness” (D&C 109:13). We all have our faith-promoting stories, told in brilliant variety, of unbelievers attending a temple openhouse and being astonished and con verted by the spirit felt. Likewise we take literally the notion of “unclean” persons’ ability to “pollute” sacred places, prayers, and events merely by their presence (D&C 109:20). The charged influence of the sacred isn’t a necessary force, however; and we often talk of a person’s ability to resist the Spirit or ignore the sacred atmosphere of the temple, perhaps because their conscience has been seared as with a hot iron (1 Tim. 4:2). On the other hand, Mormons are great proponents of modern science and likewise tend to be amenable to naturalistic explanations of miracles. We’ve all heard discussions of Christ’s complete ocular understanding, which allowed him to heal the blind man. It is precisely the way in which we comfortably, even casually, operate with both interactive understandings that is often so off-putting to our secular and more modern friends, inviting accusations concerning the backward, superstitious beliefs of Mormons.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2: Types of Self and Interaction, see PDF below, p. 105]

Regardless of whether I am entirely correct in my situating of Mormon notions of the sacred, I think this model is a potential step forward in our attempt to understand ourselves vis-!-vis the broader social context. Something like this model is necessary if we desire to have a two-way dialogue, assisting scholars in the work of explaining Mormonism to the world and likewise helping everyday Mormons to a greater self-understanding of their faith and faithful experiences. Learning to appreciate and articulate the nuanced differences between our experience and that of others within a broader framework is not just the model for successfully explicating our history. Building on the work of the Sterling McMurrins and Truman Madsens of our past, it is also the model for successfully explicating our philosophical, theological, and cultural traditions.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue