Articles/Essays – Volume 47, No. 3

Celestial Terms | In the Night | Tangled Women

Celestial Terms

You love me in algebra—

D + d = L to the Nth degree,

and I love you in quarter notes—

a fierce appoggiatura and a soft, high C.

We loved each other then in

a jumble of chords using mostly black keys,

in square roots, and Pi with ice

cream, and the straining of infinity.

We passed my childhood in a

barrage of love-fear-grief-love—our Symphony.

When firmaments fell, you were

quiet. You held your anger safe from me.

At my wedding dance (neither

of us dances) we circled awkwardly,

and when I left the house for good

I looked up the long, steep length of driveway

and choked on my new freedom.

I couldn’t picture what my life would be.

And now, we tiptoe on the phone

(not our favorite). But then, last Christmas Eve

we debated math, Ron Paul,

and the theory of relativity,

and my poor husband went to bed

with a titan headache, like Sicily

invaded by the Romans.

But it is the inevitability

of you and me, the red-haired

inventor and blond pigtailed girl, hungering

for the best of what you could

(D+d) and could not quite give to me:

Someday we will share feelings.

In celestial terms they’ll zip, from heart to

heart, like electricity

elegant with algorithms, channeled in

raw-sung soliloquies.

In the Night

We slumber heavy in the night

so long as hills are bare and white

and what is real, is pressing. What

can you do but answer. What can

you do but take my jaw in hand

and answer. And what can I, but

know you while night visions press us, hot

in our down blanket. What cannot

be spoken, we will speak with night

still resting on us—your air

on me, and my warm shoulder bare

to you—real, real as day is light

until we wake in morning’s cold,

when mountains, rimming in the gold

of cresting sun, can no more be

deferred. What can we do but rise . . .

that I could stop you with my gaze

as you work your task of leaving me.

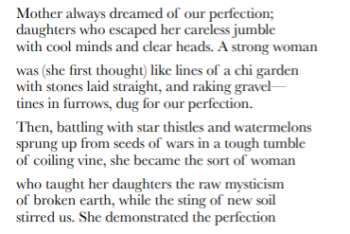

Tangled Women

Mother always dreamed of our perfection;

daughters who escaped her careless jumble

with cool minds and clear heads. A strong woman

was (she first thought) like lines of a chi garden

with stones laid straight, and raking gravel—

tines in furrows, dug for our perfection.

Then, battling with star thistles and watermelons

sprung up from seeds of wars in a tough tumble

of coiling vine, she became the sort of woman

who taught her daughters the raw mysticism

of broken earth, while the sting of new soil

stirred us. She demonstrated the perfection

of bulbs thrown, of planting in the pattern

of scatter. With closed eyes, she tossed her handful

in hope that we would all grow to be women

of choice. What renaissance—the perfection

of rebellion in us, tangled women.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue