Articles/Essays – Volume 17, No. 3

Book of Mormon Usage in Early LDS Theology

Within Mormon scholarship, one trend for the 1980s is already discernible — an increasing interest in doctrinal history, or what is more properly called “historical theology.” Historical theology can be broadly defined as the study of the “classical thinking of the church in its effort through the ages to express [the revelation of God] and to apply it as a guide through the perplexities and ambiguities of life.[1] Articles dealing with “classical” Mormon thought on the nature of God, the Holy Ghost, the pre-mortal existence, the millennium, and evolution, to name just a few, have all appeared in scholarly journals since 1980.[2] The rise of the annual Sunstone Theological Symposium further testifies of, at the same time that it encourages, a heightened sensitivity to “doctrinal development.”

Yet, there is another dimension of historical theology that must be considered if this nascent Mormon venture is to be anchored to a sure foundation. In Historical Theology: An Introduction, Geoffrey Bromiley points out that since theology is “the church’s word about God in responsive transmission of the Word of God to the church,” its cornerstone is necessarily scriptural exegesis.[3] Simply put, any doctrinal formulation grows out of the interpretation of scripture. Thus, exegetical history is at the core of historical theology. Among LDS scholars, however, exegetical history is almost virgin territory. In 1973, Gordon Irving published an article detailing the results of his research into early Mormon use of the Bible (1832-38), but his well-regarded study has yet to be either extended in time or replicated for the other Mormon scriptures.[4] Such research will ultimately issue in full-scale exegetical histories of each of the four volumes in the LDS canon, but it will doubtless require the work of many individuals over many years. As one step in that direction, this article explores Book of Mormon usage in the pre-Utah period (1830—46), and seeks answers to the following questions: Which passages from the Book of Mormon were cited and with what frequency? How were they understood? What does their usage reveal about the content and nature of early LDS theology?[5]

In order to answer these questions with a degree of comprehensiveness, I searched all major Church periodicals published before 1846 — The Evening and the Morning Star (1832-34), Messenger and Advocate (1834-37), Elders’ Journal (1837-38), Times and Seasons (1839-46), and Millennial Star (1840-46) — for Book of Mormon citations and commentary.[6] In addition, the study included some seventy Mormon “books” — what would today be called tracts or pamphlets. These sources, hereafter referred to collectively as “the early literature,” plus a handful of journals[7] and other unpublished items checked for comparative purposes, yielded a total of 243 citations, classified in Table 1.

Two additional items require special introduction. Little is certain about the origin of References to the Book of Mormon, the earliest known reference guide to the Book of Mormon, but bibliographers conclude that the four-page item of unknown authorship was printed in Kirtland in 1835.[8] Arranged chronologically, References is more of an extended table of contents than a topical index, but its 254 brief entries are phrased revealingly (“Nehor the Universalian” or “the Zoramites preach election”). Similar in format is an index prepared by Brigham Young and Willard Richards for the 1841 European edition of the Book of Mormon.[9] The Young-Richards Index is almost twice as long as the 1835 References, though 38 percent of its entries are either identically worded or altered insignificantly. Together, these indexes provide yet another perspective for ascertaining early Mormon perceptions of the Book of Mormon. As any index, though, they reflect what the compilers considered potentially useful or interesting to their readers, as opposed to what was actually used in the early literature. Furthermore, early LDS literature represents dozens of documents and thousands of pages while the indexes are only two items of several pages each. For these reasons, they play a supplementary rather than a primary role in this study. Nonetheless, these hitherto neglected documents are valuable in a study of Mormon intellectual history and are reproduced in full as an appendix. For reader accessibility, both indexes have been referenced to the modern edition of the Book of Mormon and placed comparatively in parallel columns.[10]

Table 1

Early Literature Sources Ranked by Number of Citations

| Periodical | Volume | Number of Citations | ||

| The Evening and the Morning Star | (1) | 45 | Charles Thompson, Evidences in Proof of Book of Mormon (1841) | 21 |

| Millennial Star | (6) | 20 | Benjamin Winchester, Gospel Reflector (1841) | 10 |

| Times and Seasons | (3) | 14 | Parley Pratt, Truth Vindicate (1838) | 7 |

| Messenger and Advocate | (1) | 11 | John Whitmer, “Book of John Whitmer” | 5 |

| Times and Seasons | (5) | 11 | Parley Pratt, The Millennium and other poems (1840) | 5 |

| Times and Seasons | (2) | 9 | Parley Pratt, Voice of Warning (1837) | 4 |

| Millennial Star | (1) | 8 | John Corrill, History of Mormons (1839) | 4 |

| Messenger and Advocate | (2) | 7 | Orson Pratt, Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions (184) | 3 |

| Millennial Star | (7) | 7 | Emma Smith, Hymns (1835) | 1 |

| The Evening and Morning Star | (2) | 6 | Daniel Shearer, A Key to the Bible (1844) | 1 |

| Millennial Star | (2) | 6 | Lorenzo Barnes, References (1841) | 1 |

| Times and Seasons | (6) | 5 | Orson Hyde, A Voice from Jerusalem (1842) | 1 |

| Times and Seasons | (1) | 5 | Parley Pratt, Plain Facts (1840) | 1 |

| Millennial Star | (3) | 3 | 64 | |

| Elders’ Journal | 2 | |||

| Times and Seasons | (4) | 2 | ||

| Millennial Star | (5) | 1 | ||

| 162 | Journals | 17 |

Content Analysis

Table 2 identifies the Book of Mormon chapters and verses which were most frequently cited during the period under study. The subjects treated in Table 2 scriptures are noted in Tables 3 and 4. Table 3 lists and annotates every passage cited more than once in early literature, and Table 4 ranks the themes most commonly developed from Book of Mormon passages. Both the annotations and the classifications are based on period perceptions.

What becomes clear, especially in Table 4, is the thematic preeminence of that cluster of concepts which the early Saints lumped together under the rubric of the “restoration of Israel.” In order to appreciate fully their preoccupation with this topic, we must first set Mormon views in the broader context of western Christianity.[11] From the Council of Ephesus in 431, until the time of the Reformation, Augustinian eschatology prevailed. In his City of God, the Bishop of Hippo allegorized the millennium, identifying it with the period of church history from the time of Christ to the end of the world. Since the church was the antitype of Israel, it fulfilled all Old Testament prophecies of Israel’s future glory. Thus, there was no need for nor propriety in a latter day work among the literal descendants of the House of Israel. After the Reformation had been underway a few decades, however, certain of Calvin’s followers began to teach that toward the end of the world a wide spread conversion of the Jewish people would occur. Some even began following rabbinic exegesis of Old Testament prophecies and postulated a literal restoration of Israel to Palestine. For these divines, such terms as “Israel,” “Judah,” “Jerusalem,” and “Zion” required literal interpretation. They referred to the actual site of the sacred city, rather than being mere metaphors of the church. This significant shift occurred in the late 1500s and early 1600s and crossed the Atlantic with the Puritans.

Table 2

Most Common Citations from Early Literature

| Chapters | Number of Times | Specific Passages | Number of Times |

| 3 Ne. 21 | 16 | Eth. 13:4–8 | 8 |

| 3 Ne. 16 | 13 | 3 Ne. 21:1-7 | 7 |

| 3 Ne. 3 | 10 | 2 Ne. 30:3-6 | 7 |

| 2 Ne. 29 | 10 | 2 Ne. 3:4-21 | 6 |

| 2 Ne. 30 | 10 | 2 Ne. 29:3 | 5 |

| 2 Ne. 28 | 9 | 3 Ne. 8:5-9:12 | 5 |

| 3 Ne. 20 | 9 | 1 Ne. 22:6-12 | 4 |

| Eth. 13 | 8 | 3 Ne. 15:11-16:4 | 4 |

| 1 Ne. 22 | 8 | Eth. 2:7-12 | 4 |

| Morm. 8:29-30 | 4 |

Table 3

An Annotated List of Passages Cited More Than Once in Early Literature

| Number of Times Cited | ||

| 1 Nephi | ||

| 1:14 | 2 | Rhetorical exclamation |

| 13:26 | 2 | Plain and precious parts of Bible removed |

| 22:6-12 | 4 | Indians gathered by United States |

| 22:20-22 | 3 | Identity of Moses-like prophet |

| 2 Nephi | ||

| 3:4-21 | 6 | Blessings to and through Joseph |

| 5:14-16 | 2 | Explains archaeological findings |

| 28:3-17 | 3 | Gentile corruption |

| 29:3 | 5 | A Bible, A Bible: Gentile complaint |

| 30:3-6 | 7 | Indians restored |

| 30:7-8 | 3 | Jews gathered |

| 31:5-10 | 2 | Jesus and baptism |

| Jacob | ||

| 2:2-4 | 2 | More than one wife forbidden |

| 5:19-22 | 2 | Ten tribes |

| Alma | ||

| 13:7, 8, 17-19 | 2 | Melchizedek priesthood |

| 22:32 | 2 | Explains archaeological findings |

| 34:17-23 | 2 | Prayer |

| 48:7-8 | 2 | Explains archaeological findings |

| 49:18 | 2 | Explains archaeological findings |

| 50:1-6 | 3 | Explains archaeological findings |

| 3 Nephi | ||

| 8:5-9:12 | 5 | Explains archaeological findings |

| 11:20-40 | 3 | Baptism and gospel basics |

| 15:11-16:4 | 4 | “Other sheep” of Israel |

| 16:4-7 | 3 | Gathering of Israel (Indian) |

| 16:8-16 | 3 | Fate of unbelieving Gentiles |

| 16:10 | 3 | Exodus to Utah fulfills |

| 20:22 | 2 | Gathering of Israel |

| 20:43 | 2 | Joseph Smith |

| 21:1-7 | 7 | Sign that restoration of Israel has commenced |

| 21:1-29 | 3 | Restoration of Israel (Indians) |

| 21:11-15 | 2 | Fate of unbelieving Gentiles |

| 21:10 | 2 | Joseph Smith |

| 27:13-22 | 2 | Nature of gospel |

| 28:7 | 2 | Second Coming |

| Mormon | ||

| 8:29-30 | 4 | State of world when Book of Mormon discovered |

| Ether | ||

| 2:7-12 | 4 | Decree concerning America |

| 5:2-4 | 2 | Three witnesses |

| 12:30 | 2 | Faith moves mountains |

| 13:4-8 | 8 | An American New Jerusalem designated for gathering of Joseph |

Table 4

Principal Themes Based on Classification of Book of Mormon Passages Cited

| Restoration of Israel | |

| Gathering of Israel (General) | 28* |

| Joseph (Indians) | 16 |

| Jews | 6 |

| New Jerusalem | 6 |

| Ten Tribes | 3 |

| Total (Restoration of Israel) | 59 |

| Prophecy Relating to Gentiles | |

| State of Christendom in 1830 | 16 |

| America: repent or suffer | 15 |

| General | 6 |

| Total (Prophecy Relating to Gentiles) | 37 |

| Archaeological Evidences | 32 |

| Atonement | 23 |

| Joseph Smith | 14 |

| First Principles of Gospel | 13 |

| Concern for Holiness | 11 |

| Revelation and Spiritual Gifts | 7 |

*Each passage is classified only once

Of course, not all Christians were persuaded by this view. Fundamentally, it was a matter of hermeneutics. If one thought that the prophecies ought to be interpreted allegorically or figuratively, then no Jewish conversion to Christ was expected. On the other hand, a literalist anticipated a wholesale conversion of the Jews and an actual return to their ancestral homeland. Both schools of thought and various shades in between were present in 1830. Though Mormon hermeneutics represented a literalist/allegorist blend, Mormon scriptures, especially the Book of Mormon, provided for striking innovations in their interpretation of the “latter day glory.”

To begin with, the book allowed early Saints to move beyond a discussion of Israel’s identity and destiny that involved only the Jews. As Joseph Smith explained to an eastern editor, through the Book of Mormon “we learn that our western tribes of Indians are descendants from that Joseph which was sold into Egypt, and that the land of America is a promised land unto them.”[12] That their Native American neighbors were as Israelitish as any Jew had long been suspected by others; that the whole prophetic scenario of a gathering to Zion and a restoration to glory was to be dually enacted — on American soil by native inhabitants and simultaneously by the Jews in the Old World — added a new dimension to the drama.[13] To be sure, the Saints still followed newspaper accounts of Zionistic stirrings among the Jews with the usual millenarian enthusiasm, but they also believed in a local Zion, as real as the ancient Jerusalem, and in a local people, as pedigreed as the Jews, to be gathered to that holy city in fulfillment of ancient prophecy.

As the Saints readily acknowledged, the source for this revolutionary concept was the Book of Mormon. “The vail which had been cast over the prophecies of the Old Testament,” wrote W. W. Phelps, “was removed by the plainness of the book of Mormon.” At last, “that embarrassment under which thousands had labored for years to learn how the saints would know where to gather was obviated by the book of Mormon.”[14] And it was Ether 13 :4-8, more than any other passage, that was responsible for this revelation:

Behold, Ether saw the days of Christ, and he spake concerning a New Jerusalem upon this land. And he spake also concerning the house of Israel, and the Jerusalem from whence Lehi should come — after it should be destroyed it should be built up again, a holy city unto the Lord; wherefore, it could not be a new Jerusalem for it had been in a time of old; but it should be built up again, and become a holy city of the Lord; and it should be built unto the house of Israel. And that a New Jerusalem should be built upon this land, unto the remnant of the seed of Joseph . . . Wherefore, the remnant of the house of Joseph should be built upon this land; and it shall be a land of their inheritance; and they shall build up a holy city unto the Lord, like unto the Jerusalem of old.

In the heyday of manifest destiny, it was not popular to assert, as did the Mormons, that America actually belonged to the Indians and would be their millennial inheritance. While they frequently pointed out, using parts of 3 Nephi 16, 20, and 21, that all EuroAmericans, or “gentiles,” who repented would be “numbered among this the remnant of Jacob,” such an “adopted” status, even if it did entitle them to all related blessings, seemed to reverse con temporary caste distinctions.[15] Even more calculated to raise hackles was the sharply drawn alternative. Speaking of unrepentant gentiles — the Saints’ nonbelieving neighbors — Parley P. Pratt assured the Indians that

the very places of their [Gentiles] dwellings will become desolate except such of them as are gathered and numbered with you; and you will exist in peace, upon the face of this land from generation to generation. And your children will only know that the Gentiles once conquered this country and became a great nation here, as they read it in history; as a thing long since passed away, and the remembrance of it almost gone from the earth.[16]

Such rhetoric, to say the least, seemed unduly solicitous of the lowly Indian, but the drama only intensified when the “ways and means of this utter destruction” were discussed. On three different occasions during his postmortal minis try in the New World, the Savior applied the words of Micah to an American setting.[17] If the gentiles reject the new covenant offered in the latter days through the Book of Mormon, then

my people who are a remnant of Jacob [Indians] shall be among the Gentiles yea, in the midst of them as a lion among the beast of the forest, as a young lion among the flocks of sheep, who, if he go through both treadeth down and teareth in pieces, and none can deliver. Their hand shall be lifted up upon their adversaries, and all their enemies shall be cut off. (3 Ne. 21:12-13; cf. Mic. 5:8-9)

Nothing here was figurative to the early Saints. Book of Mormon prophecies, wrote Pratt, “are plain, simple, definite, literal, positive and very ex press.”[18] As for Jesus’ words, Pratt explained, “This destruction includes an utter overthrow, and desolation of all our Cities, Forts, and Strong holds — an entire annihilation of our race, except such as embrace the Covenant and are numbered with Israel.”[19] Another who believed the passage “very express” was Charles G. Thompson, presiding elder of the Genesee New York, Conference of the Church. In his “Proclamation and Warning,” he intoned,

wo, wo, wo unto you, O ye Gentiles who inhabit this land, except you speedily repent and obey the message of eternal truth which God has sent for the salvation of his people. . . . Yea, except ye repent and subscribe with your hands unto the Lord, and sir-name yourselves Israel, and call yourselves after the name of Jacob, you must be swept off, for behold your sins have reached unto heaven. . . . The cries of the red men, whom ye and your fathers have dispossessed and driven from their lands which God gave unto them and their fathers for an everlasting inheritance, have ascended into the ears of the Lord of Sabaoth.[20]

Even without the “paranoid style” prevalent in antebellum America, it is understandable that such pro-Indian rhetoric would have caused many out siders to think there was a treasonous conspiracy against the United States in the offing.[21] Yet the Saints categorically rejected the Mohammedan metaphor. In the words of a Millennial Star editorial:

We wish it distinctly understood that the interpretation given to the Mormon predicdictions as to the Latter-Day Saints drawing the sword against others who may differ from them in religious belief is without shadow of truth, being contrary to the whole spirit of the Christian religion, which they (the Saints) profess; and however the Lord may see fit to make use of the Indians to execute his vengeance upon the ungodly, before they (the Indians) are converted by the record of their fore-fathers, yet it is certain that if they once become Latter-day Saints they will never more use weapons of war except in defence of their lives, and liberties. The Latter-day Saints never did draw the sword except in defence of their lives and the institutions and laws of their country, and they never will.[22]

That few whites in antebellum America had a more expansive, almost romantic, vision of what lay ahead for the Native American is also made clear from the Saints’ exegesis of the popular passage 2 Nephi 30:3-6. Nephi here prophesies that the Book of Mormon would someday come through the gentiles to the “remnant” of his “seed” and would be the means of restoring them “unto the knowledge of their fathers, and also to the knowledge of Jesus Christ.” As a result, his posterity would “rejoice” and the “scales of darkness shall begin to fall from their eyes.” In time, they “shall be a white and a de lightsome people.”[23] As might be expected, literalist Latter-day Saints anticipated an actual blanching of the skin. Watching the implementation of President Andrew Jackson’s removal policy, W. W. Phelps waxed visionary and predicted the imminent fulfillment of this passage. “The hour is nigh,” he wrote, when the Indians “will come flocking into the kingdom of God, like doves to their windows; yea, as the book of Mormon foretells — they will soon become a white and delightsome people.”[24]

Still an important aspect of the LDS conception of the “restoration of Israel” was the traditional millenarian anticipation of the return of the Jews. What was new with the Mormons was the idea that the Book of Mormon would be the key to their national conversion. Commenting upon portions of 2 Nephi 29 and 30, Benjamin Winchester, an early Mormon pamphleteer and one-time president of the important Philadelphia branch of the church, remarked that it “will be a testimony that will not be easily dispensed with; consequently the Jews will search deep into the matter and peradventure learn that Jesus is the true Messiah. Hence we see the utility of the Book of Mormon.”[25]

The Book of Mormon also alluded to the “lost” ten tribes of Israel. Jacob 5, or the “parable of the olive tree,” as it was known in the early years, spoke of “natural branches” being “hid” in the “nethermost part of the vineyard,” which also happened to be the “poorest spot.” This seemed to coincide perfectly with current notions about the tribes having been sequestered away to the frozen “north countries.” In a letter to Oliver Cowdery, W. W. Phelps postulated:

The parts of the globe that are known probably contain 700 millions of inhabitants, and those parts which are unknown may be supposed to contain more than four times as many more, making an estimated total of about three thousand, five hundred and eighty millions of souls; Let no man marvel at this statement, because there may be a continent at the north pole, of more than 1300 square miles, containing thousands of millions of Israelites, who, after a highway is cast up in the great deep, may come to Zion, singing songs of everlasting joy. . . . This idea is greatly strengthened by reading Zenos’ account of the tame olive tree in the Book of Mormon. The branches planted in the nethermost parts of the earth, “brought forth much fruit,” and no man that pretends to have pure religion, can find “much fruit” among the Gentiles, or heathen of this generation.[26]

This last thought about the lack of “fruit” among the Gentiles (Matt. 21:43; Rom. 11), though here mentioned only in passing, was actually central to the Saints periodization of redemptive history. God had originally offered the kingdom to the Jews but in time they ceased to “bring forth the fruits thereof.” During New Testament times, it was taken from them and offered to the gentiles with the warning that, should they too cease to produce the fruits of godliness, they would be “cut off” and the Israelites “grafted” back in. This final shift of divine favor to the ancient covenant people would culminate in the millennium and represent the climactic conclusion to the “restoration of Israel.” The necessary antecedent, however, was the apostasy of Christendom. As Sidney Rigdon expressed it, the latter day gathering of Israel was “predicated on . . . the Gentiles having forfeited all claim to the divine favor by reason of their great apostasy.”[27]Once that precondition was met, the drama was ready to proceed.

Not surprisingly, Book of Mormon passages dealing with the latter-day status of the gentiles attracted exegetical attention second only to the theme of Israel’s restoration. (See Table 4). Among the relevant scriptures, 2 Nephi 28 was often cited in the early years. Because it was generally introduced by writers as a “plain” prophecy needing no commentary, the two indexes to the Book of Mormon provide helpful supplementary material. In the 1835 Refer ences, there is one entry for 2 Nephi 28: “State of the Gentiles in that day.” In the 1841 Index, this is amplified to include three listings: “Their priests shall contend,” “Teach with their learning & deny the Holy Ghost,” and “Rob the poor.” Phraseology of these entries allows us to pinpoint several of the key verses:

For it shall come to pass in that day that the churches which are built up, and not unto the Lord, when the one shall say unto the other: Behold, I am the Lord’s; and the others shall say: I, I am the Lord’s and thus shall every one say that hath built up churches, and not unto the Lord. And they shall contend one with another; and their priests shall contend one with another, and they shall teach with their learning, and deny the Holy Ghost, which giveth utterance. (2 Ne. 28:3-4)

Remembering what sent Joseph Smith to the Sacred Grove and recognizing that many converts expressed similar concern over the multitude of competing sects, it is easy to see how such verses would have both explained the religious world around them and confirmed the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

On one of his many missionary tours, Heber C. Kimball wrote, “We de livered our testimony to many [ministers] who with one consent said ‘we have enough and need no more revelation’; thus fulfilling a prediction of the Book of Mormon.”[28] The passage Kimball was referring to was 2 Nephi 29:3 which says that because of the book “many of the Gentiles shall say: A Bible! A Bible! We have got a Bible, and there cannot be any more Bible.” This passage seemed to be fulfilled at every turn of the corner. “The vanity, the unbelief, the darkness and wickedness of this generation has caused many to fulfill the predictions of Nephi,” wrote the editor of the Messenger and Advocate.[29] Predicted in prophecy, the book’s frequent rejection thus ended up promoting faith rather than sowing doubt. Perhaps more importantly, it served as one more testimony that gentile Christendom had become effete and that the stage was thus fully set for that final act in the redemptive drama — the resto ration of Israel.

Even the very birth of the Book of Mormon was an unmistakable witness that the “winding-up scenes” were underway. The second most frequently cited series of verses in the early literature was 3 Nephi 21:1-7. The Savior prom ised the Nephites “a sign that ye may know the time when these things shall be about to take place — that I shall gather in from their long dispersion, my people, O house of Israel.” That sign, as he went on to explain, was the Book of Mormon itself and “it shall be a sign unto them, that they may know that the work of the Father hath already commenced unto the fulfilling of the covenant which he hath made unto the people who are of the house of Israel.” As Parley P. Pratt remarked, this, and other similar passages

show, in definite terms not to be misunderstood, that, when that record should come forth in the latter day, and be published to the Gentiles, and come from them to the house of Israel, it should be A SIGN, A STANDARD, AN ENSIGN, by which they might KNOW THAT THE TIME HAD ACTUALLY ARRIVED FOR THE WORK TO COMMENCE AMONG ALL NATIONS, IN PREPARING THE WAY FOR THE RETURN OF ISRAEL TO THEIR OWN LAND.[30]

Thus, the Book of Mormon served as an invaluable prophetic landmark, a millenarian milestone that helped the Saints to locate themselves in the eschatological timetable.

Before leaving the prophetic portions of the Book of Mormon, we must con sider the Saints’ fascinating use of the book to justify and explain the life of Joseph Smith. 2 Nephi 3 records the prophecy of Joseph who was sold into Egypt that a “choice seer” would be raised up to bless the “fruit of his loins.” In verse 15, he identifies the individual quite precisely: “His name shall be called after me; and it shall be after the name of his father. And he shall be like unto me.” Such specific prophecy and its exact fulfillment in Joseph Smith, Jr., obviously appealed to literalist Latter-day Saints. In the church’s first hymnbook a song appeared in which this correlation between antiquity and actuality was extolled:

He likewise did foretell the name,

That should be given to the same,

His and his father’s should agree,

And both like his should Joseph be.

The song goes on to encapsulate the essential significance that this popular portion of the Book of Mormon probably held for the average Saint:

According to his holy plan,

The Lord has now rais’d up the man,

His latter day work to begin,

To gather scatter’d Israel in.

This seer shall be esteemed high,

By Joseph’s remnants by and by,

He is the man who’s call’d to raise,

And lead Christ’s church in these last days.[31]

All the important elements of Joseph Smith’s mission are present—the gathering of Israel, the conversion of the Indians, and the connection with the institutional church.

For ages individuals have found refuge from the unknown in the security of prophecy. That Mormons, therefore, discovered comforting scriptural assurances that their leader would be protected and his work would not be cut short is to be expected. After receiving word of Joseph Smith’s 1841 acquittal in Quincy, Illinois, a distant Parley Pratt editorialized in the Millennial Star, “Be it known that there is an invisible hand in this matter,” and then he quoted 2 Nephi 3:14: “THAT SEER WILL THE LORD BLESS, AND THEY WHO SEEK TO DESTROY HIM SHALL BE CONFOUNDED.” As evidence, Pratt cited “some twenty times in succession” in which Joseph’s enemies had tried to destroy him legally but had been foiled each time. This, commented Pratt “is sufficient of itself to establish the truth of the Book of Mormon.”[32]

Even more popular than the promised preservation was a pair of passages from 3 Nephi. In his visit to the Americas, the Savior quoted various parts of the Isaiah prophecies. One such segment was the concluding verses from Isaiah 52, where speaking of “the servant” he says, “his visage was so marred, more than any man, and his form more than the sons of men” (3 Ne. 20:43— 44). For centuries Christian exegetes had considered this one of the great Messianic prophecies of Christ’s scourging and crucifixion. Yet in a passage cited by the early Saints, the risen Lord himself gave it another meaning. Speaking of a latter day context and of a “servant” who would be instrumental in bringing about the “great and marvelous work,” Jesus said, “and there shall be among them those who will not believe it, although a man shall declare it unto them. But behold, the life of my servant shall be in my hand; there fore they shall not hurt him, although he shall be marred because of them. Yet I will heal him, for I will show unto them that my wisdom is greater than the cunning of the devil” (3 Ne. 21:9-10).

The 1835 References labels these verses, “Joseph the seer spoken of,” and in the 1841 Index, it reads “He shall be marred.” In a Nauvoo Neighbor editorial, John Taylor explained the prophecy thus: “This ‘marring’ happened near the hill Cummorah, when Joseph Smith was knocked down with a hand spike, and afterwards healed almost instantly \ The second time he was marred” occurred in March 1832 “when his flesh was scratched off, and he tarred and feathered. He was again healed instantly, fulfilling the prophecy twice.” But for Taylor there was a critical distinction between being “marred” and being martyred, for Taylor pointed to 1 Nephi 20:19 as evidence that Joseph’s death had actually been anticipated in prophecy.[33] Like Parley Pratt’s use of 2 Nephi 3:14, then, it seems that for early Saints Joseph Smith’s tribulations at once certified the authenticity of the Book of Mormon and imparted divine significance to what was happening in his life.

Occasionally, such parallels between Joseph Smith and Jesus Christ led to novel exegesis. Following the dark days of the Kirtland apostasy, apostle David W. Patten attempted to curb some of the faultfinding by writing an epistle “to the Saints scattered abroad.”[34] His text, Romans 11: 25-26, was a traditional favorite among millenarian Christians. It spoke of Israel’s salvation in the latter days being effected by a “Deliverer” who “shall come out of Sion” and “shall turn away ungodliness from Jacob.” Despite the fact that other Mormon commentators such as Parley Pratt followed the traditional interpretation of the “Deliverer” as Christ, Patten used 2 Nephi 3 and 3 Nephi 20 along with numerous Biblical passages to prove that this “Deliverer” was in reality Joseph Smith.

If apologetics produced apotheosis, so did the enthusiasm of converts. While Patten’s interpretation was unusual, a more common mixing of the roles of Jesus and Joseph occurred when explaining the identity of “the prophet” spoken of by Moses in Deuteronomy 18:15-19, although the Saints usually followed the phrasing of Acts 3:22-23. On two occasions it was deemed worthwhile to print clarifications in Church periodicals. In both instances, passages from the Book of Mormon were invoked. The Evening and the Morning Star published a letter asserting that the problem lay in “not knowing the scriptures, on the subject, especially the book of Mormon. For Christ said, when he showed himself to the Nephites, Behold, I am he of whom Moses spake, saying: A prophet shall the Lord your God raise up.”[35] In Nauvoo, the editor of the Times and Seasons cited a similarly clear passage from 1 Nephi “where the matter is fully set at rest” as to the messianic identity of the “prophet.” Nonetheless, the high regard in which Joseph Smith was held among the Saints caused the editor to tread lightly:

If any are fearful lest we, by our interpretation, wrest a gem from the crown of our beloved prophet, let them remember, that we place it in the royal diadem of him who is more excellent than Joseph; and where even Joseph will be pleased to have it remain and shine. That God hath exalted him to a station of great dignity and responsibility, we do not doubt, but the truth of it rests on other testimony than the above.[36]

While the primary focus of this article is theological, the prominent use of the Book of Mormon passages to explain contemporary archaeological or scientific findings (Tables 3, 4) deserves brief discussion. The first half of the nineteenth century probably saw the relationship between science and religion reach its apex. In America, where the twin ideals of Scottish Common Sense philosophy and the Baconian inductive method reigned supreme, the association was especially congenial.[37] During this Indian summer before Darwin seemingly dealt the death blow to biblical literalism, a plethora of publications confidently set forth the “evidences of Christianity.” The undergirding faith of this literature was simple. “The God of science was after all the God of Scripture,” explains religious historian George Marsden. “It should not be difficult to demonstrate, therefore, that what he revealed in one realm perfectly harmonized with what he revealed in the other. The perspicuity of nature should confirm the perspicuity of Scripture.”[38]

Such, too, was the faith of the Saints when it came to establishing the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. No one doubted for a moment that what explorer John L. Stephens was discovering in Central America and the Yuca tan in the early 1840s was tangible testimony to the book’s truthfulness. The tower at Palenque was surely the temple mentioned in 2 Nephi 5; the ruins of Quirigua almost certainly the city of Zarahemla; and the Isthmus of Darien (Panama) the “narrow neck of land.”[39] Extracts from Stephens’s book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, & Yucatan, were published in church periodicals with considerable jubilation. “It affords us great joy,” wrote the editor of the Times and Seasons, “to have the world assist us to so much proof.”[40]

The last major theme to be mentioned is the Atonement. Though positioned fourth overall in Table 4, this rating distorts its actual topical significance in the early years. Nearly 90 percent of all passages cited on the subject came from one 1845 article in the Millennial Star. T. S. Barr, a Mormon priest in the Glasgow Church, published a twenty-eight-page pamphlet entitled A Treatise on the Atonement, proving the necessity of Christ’s Death for Man’s Redemption neither scriptural nor reasonable. Naturally, the pamphlet came to the attention of Church leaders in England, and Wilford Woodruff, “President” of the church in the British Isles, responded with an article entitled “Rationality of the Atonement.” His introductory comments tell the whole story:

We are sorry to be under the necessity of occupying our time and pages in noticing a pamphlet bearing such an introduction, as the production of a member of the Church of Christ; or that any man, bearing any portion of the authority of the holy priesthood, should have his mind so much overcome by the powers of darkness, as to stray so widely from the order and counsel of the kingdom of God, in presenting for the investigation of the public a heresy so much opposed to the revelations of God and every principle of holiness.

Our object in the present article will not be so much to refute the heretical doc trine advanced, as to introduce a portion of the testimony in favour of the principle of redemption through the blood of Christ, with which the revelations of God so much abound, in order that our views on the subject may be rightly understood by all, and that the Saints of God may be prepared to withstand the assaults of the grand enemy of man’s salvation, as well as to set the matter for ever at rest in the minds of those who believe in the revelations of God.[41]

What follows is a chain of passages from all the standard works demonstrating that redemption did indeed come through the shedding of Christ’s blood. After arraying this arsenal of scripture, Woodruff chose a particularly poignant passage from the Book of Mormon with which to close:

Behold, will ye reject these words? Will ye reject the words of the prophets; and will ye reject all the words which have been spoken concerning Christ, after so many have spoken concerning him; and deny the good word of Christ, and the power of God, and the gift of the Holy Ghost, and quench the Holy Spirit, and make a mock of the great plan of redemption, which hath been laid for you? Know ye not that if ye will do these things, that the power of redemption and the resurrection, which is in Christ, will bring you to stand with shame and awful guilt before the bar of God? (Jac. 6:8-9)

In addition to the major themes already treated, Book of Mormon passages were occasionally used to encourage prayer, the obedience of children, and hard work.[42] They hallowed the American Revolution, explained how to con duct meetings, and promised the revelation of all truth.[43] They inveighed against salaried clergy, creeds, and contention.[44] Though these less frequent usages have transcended time and continue to this day in the LDS Church, others have not.

As the Church’s general conference convened at Nauvoo in April 1840, Orson Hyde announced that the Spirit was whispering to him to take up a mission to the Jews and Jerusalem. The expression was heartily seconded from the floor and thus began one of the most famous missions in Mormon history.[45] Two months later, in a letter written from Ohio, Hyde commented upon a Zionist movement then being reported in the newspapers. This recalled to his mind the words of Isaiah that there would be “none to guide her among all the sons she hath brought forth; neither that taketh her by the hand but these two things which are come unto thee.”[46] Noting that in the 2 Nephi 8 re capitulation of this portion of Isaiah, things appears as sons, “this is better sense, and more to the point,” declared Hyde. It also allowed him and his missionary companion, John E. Page, to step into the pages of prophecy: “As Jerusalem has no sons to take her by the hand and lead her among all the number whom she hath brought forth, Bro. Page and myself feel that we ought to hurry along and take her by the hand; for we are her sons but the Gentiles have brought us up.”[47]

An equally literalistic exegesis grew out of the Church’s decision in the fall of 1845 to evacuate Nauvoo the following spring. Rather than engage enraged vigilantes from Hancock County in what seemed to be an inevitable civil war, Church leaders decided to move west. Again, Book of Mormon prophecy helped to explain current events. According to 3 Nephi 16:10,

And thus commandeth the Father that I should say unto you: At that day when the Gentiles shall sin against my gospel, and shall be lifted up in the pride of their hearts above all nations, and above all the people of the whole earth, and shall be filled with all manner of lyings, and of deceits, and of mischiefs, and all manner of hypocrisy, and murders, and priestcrafts, and whoredoms, and of secret abominations; and if they shall do all those things, and shall reject the fulness of my gospel, behold, saith the Father, I will bring the fulness of my gospel from among them.

Early Saints expected the closing lines to be literally fulfilled in the Church’s exodus from Nauvoo. A more elaborate exegesis of this appeared in a circular entitled “Message From Orson Pratt to the Saints in the Eastern and Midland States.” Pratt was then presiding over the church in that section of the country. His analysis deserves quotation in full:

This wholesale banishment of the Saints from the American republic will no doubt, be one of the grandest and most glorious events yet witnessed in the history of this church. It seems to be a direct and literal fulfilment of many prophecies, both ancient and modern. Jesus has expressly told us, (Book of Mormon), that if the “Gentiles shall reject the fulness of my gospel, behold, saith the Father, I will bring the fulness of my gospel from among them.” Now, what could the Gentiles further do to reject the “fulness of the Gospel”—the Book of Mormon? Is there one crime that they are not guilty of? I speak of them in a national capacity. . . .

If, then, all these crimes do not amount to a national rejection of the “fulness of the gospel,” I know not what more they can do to fully ripen them in crime and iniquity. Therefore, is not the time at hand for the Lord to bring the “fulness of the gospel” from among the Gentiles of this nation? If we are banished to the western wilds among the remnants of Joseph, is it not to ripen the wicked and save the righteous? Is it not to save us from the impending judgments which modern revelations have denounced against this nation? How could the gospel be brought from among the Gentiles while the priesthood and the Saints tarried in their midst.[48]

Quantitative Analysis

As we step back to take a larger look at Book of Mormon usage in early years, we can make a number of general observations. First, compared to the Bible, the Book of Mormon was hardly cited at all. Though this present study examines a greater variety of sources over a longer period of time, Gordon Irving’s earlier analysis of Bible usage during the years 1832-38 makes a precise quantitative comparison possible for at least a six-year span of time. (See Table 5.) To a people who have come to prize the Book of Mormon as “the keystone” of their religion, it may come as a surprise to learn that in the early literature the Bible was cited nearly twenty times more frequently than the Book of Mormon. Such a ratio is corroborated in the unpublished sources as well. During his proselyting peregrinations at this period of time, Orson Pratt kept a fairly detailed record of the scriptures used in his sermons. Bible pas sages were listed ten times more frequently than Book of Mormon ones.[49] Moreover, in the 173 Nauvoo discourses of the prophet Joseph Smith for which contemporary records exist, only two Book of Mormon passages have been cited while dozens of biblical passages were.[50]

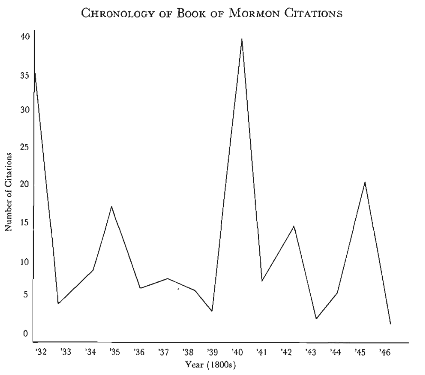

A second observation is that for the years under study a discernible pattern of usage frequency is not evident. A glance at Table 1 reveals that the 1832- 33 volume of the Evening and Morning Star contained the greatest number of citations, followed by the 1845 volume of the Millennial Star, the 1841-42 volume of the Times and Seasons, and the 1834-35 volume of the Messenger and Advocate. A similarly random pattern is also present in the column ranking the “books.” No sense of steady development across time is apparent here. This becomes especially clear in Figure 1. The fluctuations are best accounted for as a fortuitous confluence of publishing histories and contemporary affairs. There is no evidence of some changing signal or policy statement from Church headquarters. Thus, it is more appropriate to view the sharp drop in citations between 1832 and 1834, for example, as a result of much of the print space in the second volume of The Evening and the Morning Star being occupied with descriptions of the Saints’ expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri. It may also have been related to the fact that Oliver Cowdery, who replaced W. W. Phelps as editor, printed Sidney Rigdon’s exclusively biblical treatments of theology, whereas Phelps had published his own doctrinal essays containing an unusual number of Book of Mormon citations. Likewise, one accounts for the sharp peak in 1840-41 by noting that Parley P. Pratt then initiated the Mil lennial Star and that the two “books” which most heavily cited the Book of Mormon during the early years — Charles Thompson’s Evidences in Proof of the Book of Mormon and Benjamin Winchester’s Gospel Reflector — were also published at that time.

Table 5

Comparative Use of Bible and Book of Mormon

| Number of Bible Citations* | Number of Book of Mormon Citations | Bible to Book of Mormon Ratio | ||

| Evening and Morning Star 1 | (1832-33) | 294 | 45 | 7:1 |

| Evening and Morning Star 2 | (1833-34) | 246 | 6 | 41:1 |

| Messenger and Advocate 1 | (1834-35) | 357 | 11 | 32:1 |

| Messenger and Advocate 2 | (1835-36) | 142 | 7 | 20:1 |

| Messenger and Advocate 3 | (1836-37) | 193 | 0 | — |

| Elders Journal | (1837-38) | 79 | 2 | 40:1 |

| Pratt (Voice of Warning) | (1837) | 178 | 6 | 30:1 |

| Totals | 1489 | 77 | 19:1 |

*This column is taken from Gordon Irving, “The Mormons and the Bible in the 1830s,” BYU Studies 13 (Summer 1973): 479.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1, see PDF below]

Table 6 provides a chronological breakdown of citations according to theme and corresponds with Table 4. Except for a flurry in the early 1840s of archaeology-related citations generated by LDS interest in John L. Stephens’s book, Incidents of Travel in Central America and except for the 1845 cluster of passages on the Atonement emanating from a single article, treatment of the various themes seems fairly even throughout the years studied. Because the number of citations per year is relatively small, especially when divided topically, caution must be taken to avoid concluding too much from such limited data. Perhaps the safest observation to make is simply to reiterate that during the pre-Utah period, Book of Mormon usage was random, infrequent, and appears to have been largely a matter of personal preference.

[Editor’s Note: From Table 6, see PDF]

Lastly, we must consider such usage from the perspective of a book-by book analysis as displayed in Tables 7 and 8. Table 7 not only shows the number of citations drawn from each book, but also how that number corresponds to the size of each book. Were all books of equal perceived value, one would expect Mosiah, Alma, and Helaman, for example, which together constitute approximately half the Book of Mormon (Column A), to account for 50 per cent of the citations in the early literature. In actuality, they account for only 15 percent (Column C). Conversely, 3 Nephi and Ether represent just over 15 percent of the total volume of the book and yet account for nearly 45 per cent of the citations. Obviously, this tells us something about the Saints’ perceptions of the relative utility of the various books. Such data has been con verted into ratios in columns H-J to facilitate a more precise comparison. Table 8 carries the analysis a step further, showing the number of citations coming from different chapters within each book. Passages from just over a third of all Book of Mormon chapters were cited, and the particular book-by book percentages closely reflect those of Table 7. What is made clear from these two tables is that the prophetic portions of the Book of Mormon — parts of 3 Nephi, Ether, and 2 Nephi — received significantly greater attention from the early Saints than did the historical books — Mosiah, Alma and Helaman.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 7 and Table 8, see PDF]

Conclusions

With the descriptive and quantitative foundation now laid, we may con sider several of the larger questions raised by this study. How, for example, do we satisfactorily account for the comparatively few Book of Mormon citations in the early literature? What is the significance of the preponderant concern with Book of Mormon prophecies? Finally, in the grand manner of the prophet Mormon’s penchant for “and-thus-we-see” conclusions, is there something to be learned from all this?

A plausible answer to the question of why the Book of Mormon was cited so infrequently when compared with the Bible would seem to be that such a move was calculated to avoid Protestant antipathy to the “new scripture.” If the Saints built their case from the Bible, the gentiles would have no ready excuse for rejecting their testimony. Yet no evidence exists for either a formal church directive or even an informal agreement not to use the Book of Mormon in the public ministry. On the contrary, an early revelation positively instructed the elders to “teach the principles of my gospel which are in the Bible and the Book of Mormon,” and Orson Pratt, at least, seemed to feel no qualms about publicly quoting from the book when it seemed pertinent to his purposes. (See D&C 42:12.) Though a boldness to preach revealed truth when desired is more noticeable in the early years than any other particular concern that the source might be dismissed out-of-hand, still the Bible was overwhelmingly invoked. Moreover, the “regard-for-the-gentiles” argument does little to account for the equal lack of Book of Mormon citation within the household of faith.[51]

A fully satisfying answer looks more toward the Saints’ love of the Bible than to an intentional avoidance of the Book of Mormon. The image of Parley P. Pratt spending an entire winter alone in his Ohio log cabin, reveling in the opportunity to study the Bible from dawn to dusk, seems archetypal of those earnest souls who first joined the LDS community.[52] They had known the Bible from childhood but the Book of Mormon only from adult conversion. From any angle, the depth of familiarity with the Bible among antebellum Americans is staggering compared to today’s almost scripturally illiterate generation.[53] Even within the Church, the contrast between the two periods is marked. It might be hyperbole, but not by much, to picture every early member as a Bruce R. McConkie in his or her command of the holy scriptures.

After years of immersion in biblical studies, it is small wonder that an early revelation would have to chide the Saints for having “treated lightly the things you have received” and charge them to “remember” the Book of Mormon (D&C 84:54-57). And if, as this study demonstrates, they did not immediately respond to this challenge, is that really so surprising? Modern Mormons seem to have fared little better in “remembering” the two visions, now Sections 137 and 138, added to their canon in 1976. Though these “new” revelations provide the most detailed description of the post-mortal spirit world found in Mormon scripture, many Latter-day Saints continue to cite now familiar, though less comprehensive, passages from the Book of Mormon or Doctrine and Covenants when discussing the topic. It seems to be part of the human condition to rely on the tried and true rather than the new.

Nor did the early Saints have any opportunity for formal instruction or catechization in the Book of Mormon. Sunday School and seminary classes did not exist, and if the “Lectures on Faith” prepared for the “school of the Prophets” are any indicator, the Bible monopolized what little organized study they did have. All factors considered, therefore, it seems almost inevitable that it would have taken a generation or more for the Book of Mormon to fully permeate the doctrinal consciousness of the Latter-day Saints.

When W. W. Phelps reflected upon the early “neglect” of the book, he raised a revealing question. “Has this been done,” he asked, “for the sake of hunting mysteries in the prophecies?”[54] Whether that was what drew or held the Saints to a study of the Bible (and one suspects that he is at least partially correct), a preoccupation with the prophetic has certainly been verified in the present study of Book of Mormon usage. Prophecies relating to the fate of the gentiles and to the restoration of Israel were by far the principal interests of the early Saints. In fact, as Joseph Smith declared in a Times and Seasons editorial, they have “interested the people of God in every age.” The “latter day glory” was felt to be “a theme upon which prophets, priests, and kings have dwelt with peculiar delight,” and to which “they have looked forward with joyful anticipation.”[55]

What is amply confirmed from our study, then, is the centrality of millenarianism to early Mormonism — that of all the “-logies” that make up “theology,” it was eschatology that for the Saints outweighed the rest. Though the Book of Mormon has since been used as a source for a unique LDS brand of anthropology, soteriology, and even Christology, its earliest uses were primarily eschatological. The broad conceptual sweep of millenarianism as a “cosmology of eschatology,” however, usually gets short-changed in the popular mind. Most individuals go no further than the dictionary definition and tend to see it as an eccentric preoccupation with pinpointing the time of Christ’s second coming. Its advocates are often assumed to be either socio economically disenfranchised or mentally disengaged. “Eschatology,” re marked social gospeler Walter Rauschenbusch, “is usually loved in inverse pro portions to the square of the mental diameter of those who do the loving.”[56] In reality, it is the whole dramatic conclusion to the history of redemption and integrates a wide variety of theological topics that often get compartmentalized in doctrinal discourse. Fortunately, the earlier scholarly, as well as popular, perception of millennialism-as-pathology is now almost passe. At least among newer students, millenarian thought is no longer considered the “preserve of peasants and the oppressed” or of “assorted cranks and crackpots.” On the contrary, as a recent reviewer points out, increasingly it is being realized by a second generation of scholars that “millennialism is a natural, rational, and sometimes normative force that can exert formative influence over all strata of society.”[57] Certainly this was the case in early Mormonism, for as has been demonstrated the theological millenarianism derived from the Book of Mormon was both complex and pervasive, and was, on the whole, a “rational” and “normative” force in the Church’s formative years.

Of course, as we have also seen, it could occasionally be otherwise. To be valued, scripture must speak to the age of its adherents. But if it is tethered too tightly to the times, there is the ever-present danger that some turn of events or shift in circumstances will undermine the household of faith. Caution must be urged, therefore, in ascribing eternal verity and applicability to statements that obviously bear the identifying marks of their era. And yet every age has reinterpreted scripture to impart meaning to its day. In a sense, the Christians Christianized the Old Testament, the early Mormons Mormonized the Bible, and today’s Latter-day Saints modernize the restoration scriptures. The challenge here, as elsewhere in life and as always for the Saint, seems to be one of balance, of being able to sort the essential from the peripheral, the eternal from the ephemeral, Christ from culture. In a word, it is to live relevantly “in the world,” and yet not be captively “of the world.”

[Editor’s Note: For the Appendix, see PDF below]

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Fuller Theological Seminary Catalog, 1983-84 (Pasadena, Calif.: Fuller Theological Seminary, 1982), p. 45. Book-length treatments of historical theology include J. Danielou et ah, Historical Theology (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1969); Jaroslav Pelikan, Historical Theology: Continuity and Change in Christian Doctrine (Chicago and New Haven: Corpus, 1971); Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Historical Theology: An Introduction (Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1978) ; R. P. C. Hanson, The Continuity of Christian Doctrine (New York: Seabury Press, 1981).

[2] Thomas G. Alexander, “The Reconstruction of Modern Doctrine: From Joseph Smith to Progressive Theology,” Sunstone 5 (July-Aug. 1980) : 24-33; Gary James Bergera, “The Orson Pratt—• Brigham Young Controversies,” DIALOGUE: A JOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT 13 (Summer 1980) : 7-58; David J. Buerger, “The Adam-God Doctrine,” DIA LOGUE 15 (Spring 1982) : 14-58; Blake Ostler, “The Idea of Pre-existence in the Development of Mormon Thought,” DIALOGUE 15 (Spring 1982): 59-78; Richard Sherlock, “We Can See No Advantage to a Continuation of the Discussion: The Roberts/Smith/Talmage Affair,” DIALOGUE 13 (Fall 1980): 68-78; Jeffrey E. Keller, “Discussion Continued: The Sequel to the Roberts/Smith/Talmage Affair,” DIALOGUE 15 (Spring 1982): 79-98; Grant Underwood, “Seminal versus Sesquicentennial: A Look at Mormon Millennialism,” Dialogue 14 (Spring 1981): 32-44, and “Millenarianism and the Early Mormon Mind,” Journal of Mormon History 9 (1982) : 41-51.

[3] Bromiley, Historical Theology, p. xxvi.

[4] Gordon Irving, “The Mormons and the Bible in the 1830s,” BYU Studies 13 (Summer 1973) : 473-488. In Gary P. Gillum and John W. Welch, eds., Comprehensive Bibliography of the Book of Mormon (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research & Mormon Studies, 1982), about 2,000 entries are listed. Only two attempt some sort of historical look at Book of Mormon exegesis. Even then, theirs is a peripheral concern since they are more interested in tracking general perceptions about the book. Alton D. Merrill, “An Analysis of the Paper and Speeches of Those Who Have Written or Spoken About the Book of Mormon Published During the Years of 1830 to 1855 and 1915 to 1940, to Ascertain the Shift in Emphasis” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1940); Alton D. Merrill and Amos N. Merrill, “Changing Thought on the Book of Mormon,” Improvement Era 45 (Sept. 1942): 568.

[5] Unless the wording has been changed significantly from the 1830 edition, the 1981 edition of the Book of Mormon is used throughout this article.

[6] Lesser, though important, “periodicals” which in reality were serialized tracts published as a single volume (e.g. Benjamin Winchester’s Gospel Reflector) were classified as “books.” All known early Mormon imprints are listed in Chad J. Flake, ed., A Mormon Bibliography, 1880-1930 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1978). Approximately 100 were published before 1846. Only those inaccessible because of their location in distant repositories — about two dozen — were not consulted.

[7] Journals consulted included Elden J. Watson, ed., The Orson Pratt Journals (Salt Lake City: Elden J. Watson, 1975); Dean C. Jessee, ed., “The Kirtland Diary of Wilford Wood- ruff,” BYU Studies 12 (Summer 1972): 365-99; Andrew F. Ehat, ed., “The Nauvoo Journal of Joseph Fielding,” BYU Studies 19 (Winter 1979) : 133-66. This paper does not discuss Mormon defense of specific passages cited only because they were ridiculed in anti Mormon tracts.

[8] On the 1835 References, see Flake, Mormon Bibliography, p. 545; Peter Crawley, “A Bibliography of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New York, Ohio, and Missouri,” BYU Studies 12 (Summer 1972): 505.

[9] That Young and Richards were the authors is noted in Joseph Smith, Jr., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed., rev., 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1964), 4:286.

[10] During the period covered in this article, the Book of Mormon had not yet been divided into verses, and chapter divisions were different from those presently in use. For modern convenience, all early citations mentioned in this article have been rendered according to the current Book of Mormon division of chapters and verses.

[11] For what follows, see Peter Toon, ed., Puritans, the Millennium and the Future of Israel (Cambridge & London: James Clark & Co., 1970).

[12] History of the Church 1:315.

[13] Still useful on the idea of the Hebraic origins of the Indian is Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History, 2nd ed., rev. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), pp. 34-49. For a more recent study placing this notion in the broad background of American literary history, see Richard Slotkin, Regeneration Through Violence: Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1973).

[14] “The Book of Mormon,” Evening and Morning Star 1 (Jan. 1833) : 57. The editor at this time and almost certainly the author of this unsigned article was W. W. Phelps.

[15] In early Mormon vernacular, Gentiles was essentially a generic term for Christendom. For a statement on how the term is used today, see Bruce R. McGonkie, Mormon Doctrine, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1966), pp. 310-11.

[16] Parley P. Pratt, A Voice of Warning and Instruction to All People (New York: W. Sandford, 1837), p. 189. This portion of the text was deleted by Pratt in his second edition (1839) and has not been restored in subsequent editions.

[17] 3 Ne. 16:15, 20:16-17, 21:12-13. For the purposes of this article, I assume that authorship designations made in the Book of Mormon are accurate.

[18] Parley P. Pratt, Mormonism Unveiled: Zion’s Watchman unmasked, and its author, Mr. L. R. Sunderland, exposed: Truth vindicated (New York: O. Pratt and E. Fordham, 1838), p. 13, hereafter cited as Truth Vindicated.

[19] Ibid., p. 15.

[20] Charles B. Thompson, Evidences in Proof of the Book of Mormon (Batavia, N.Y. : D. D. Wake, 1841), pp. 229-30.

[21] One of the earliest examples of this is Eber D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed (Painesville, Ohio: E. D. Howe, 1834), pp. 145-46, 197. Many years later anti-Mormon works borrow extensively from Howe. That the fear did not cease after the Saints left Missouri is apparent from its perpetuation in later works. See, for example, James H. Hunt, Mormonism (St. Louis: Ustick and Davies, 1844), pp. 280-83. Th e phrase “paranoid style” is borrowed from Richard Hofstadter, Paranoid Style in American Politics (New York: 1965).

[22] “Reply to the Preston Chronicle,” The Latter-Day Saints’ Millennial Star 2 (July 1841): 43.

[23] The 1981 edition of the Book of Mormon follows the 1840 edition, rendering the latter phrase “a pure and delightsome people”; italics mine.

[24] “Letter No. 11 ” (W. W. Phelps to Oliver Cowdery), Latter Day Saints Messenger and Advocate 2 (Oct. 1835): 193.

[25] Benjamin Winchester, Gospel Reflector 1 (1841): 129.

[26] “Letter No. 11,” p. 194.

[27] “Millennium No. I I , ” Evening and Morning Star 2 (Jan. 1834): 127.

[28] “Communications ” (Hebe r C. Kimball to Editors), Times and Seasons 2 (16 Aug. 1841): 507.

[29] “Beware of Delusion!” Messenger and Advocate 2 (Jan . 1836): 251.

[30] “The Millennium,” Millennial Star 1 (Aug. 1840): 75 (italics in original).

[31] A Collection of Sacred Hymns (Kirtland: 1835), pp. 95-96.

[32] “President Joseph Smith in Prison,” Millennial Star 2 (Aug. 1841): 63-64.

[33] Nauvoo Neighbor 2 (28 Aug. 1844): 2; reprinted in Times and Seasons 5 (2 Sept. 1844): 635.

[34] “To the Saints Scattered Abroad,” Elders’ Journal of the Church of Latter Day Saints 1 (July 1838) : 39-42; also History of the Church 3:49-54. The interpretation also appears in Noah Packard, Political and Religious Detector: In Which Millerism is Exposed (Medina, Ohio: Michael Hayes, 1843), pp. 26-27.

[35] “Letters ” (Daniel Stephens to W. W. Phelps), Evening and Morning Star 1 (March 1833): 79.

[36] “Theological,” Times and Seasons 2 (April 1841): 359-60. Th e passage cited is 1 Ne. 22:20-22, 24.

[37] The three standard treatments of the subject are George H. Daniels, American Science in the Age of Jackson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968) ; Theodore D. Boze man, Protestants in the Age of Science: The Baconian Ideal and Antebellum American Religious Thought (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977); and Herbert Hovenkamp, Science and Religion in America, 1800-1860 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978).

[38] George M. Marsden, “Everyone One’s Own Interpreter: Th e Bible, Science, and Authority in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America,” in Nathan O. Hatch and Mark A. Noll, eds., The Bible in America: Essays in Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 86.

[39] Stephens’s book has been reprinted with an introduction by Richard L. Predmore, 2 vols. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1949). Connections between Stephens’s findings and Book of Mormon sites are made in “Extract,” Times and Seasons 3 (Sept. 1842): 914; see also pp. 921, 927; 4 (Oct. 1843) : 346; 5 (Jan. 1844): 390, 406.

[40] “Extract,” Times and Seasons 3 (15 Sept. 1842): 914.

[41] “Rationality of the Atonement,” Millennial Star 6 (Oct. 1845): 113-19.

[42] Alma 34:17-23 as in Messenger and Advocate 1 (Aug. 1835) : 168-69; 2 Ne. 4:3- 6 as in Evening and Morning Star 1 (May 1833) : 93 ; and, Mosiah 23:7 as in Evening and Morning Star 1 (Nov. 1832): 47.

[43] 1 Ne. 13:14-19 as in Evening and Morning Star (Oct. 1832): 38; Moro. 6:9 as in Evening and Morning Star 1 (Apr. 1833): 88; and 3 Ne. 26:1-9 as in Orson Pratt, Re markable Visions, p. 20.

[44] 2 Ne. 26:30-31 as in Evening and Morning Star 1 (Dec. 1832): 54; 2 Ne. 28:31 as in Evening and Morning Star 1 (March 1833) : 74 and, 3 Ne. 11:29 as in Millennial Star 3 (Oct. 1842): 110.

[45] History of the Church 4:106.

[46] Isa. 51:18-19 as quoted by Hyde, Times and Seasons 1 (Aug. 1840): 156.

[47] (Extract of letter from Orson Hyde), Times and Seasons 1 (Aug. 1840) : 156—57.

[48] “Message from Orson Pratt,” Millennial Star 6 (Dec. 1845) : 191-92. See also Times and Seasons 6 (15 Nov. 1845): 1037; Millennial Star 7 (15 Jan. 1846) : 26; and Millennial Star 7 (1 Feb. 1846): 35.

[49] Elden J. Watson, ed., The Orson Pratt Journals (Salt Lake City: Elden J. Watson, 1975). A specific search was made for the period between February 1833 and November 1837 (pp. 16-94). Of the 371 entries, 281, or 76 percent, mentioned topics. Within those 281, 96 Bible citations, 10 Book of Mormon citations, and 1 D&C citation appeared. Thus the Bible to Book of Mormon ratio is about 10 to 1.

[50] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Con temporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1980), p. 230. The phraseology suggests 3 Ne. 27:21 and Moro. 8:12, 19, or 22.

[51] While the major Church periodicals and a number of Mormon “books” were written for the benefit of the Saints, nonmembers undoubtedly read them as well. Conversely, Mormons bought and read tracts explicitly geared to others denominations. Joseph Smith preached deep doctrine when nonmembers were in the congregation. The question of “audience,” therefore, that is often brought into a discussion of Mormon intellectual history bespeaks a rather presentist view. It assumes that early Mormons, like the Saints today, made conscious distinctions in their minds between what could be said to outsiders and what was reserved only for the insider. This is neither a prominent nor even a clear motif in early Mormon sources.

[52] The Autobiography of Parley Parker Pratt (New York: Russell Brothers, 1874), pp. 27-28.

[53] See, for example, Mark A. Noll, “The Image of the United States as a Biblical Nation, 1776-1865,” in Hatch and Noll, eds., The Bible in America, pp. 39-58.

[54] “Some of Mormon’s Teachings, ” Evening and Morning Star 1 (Jan. 1833): 60.

[55] “The Temple, ” Times and Seasons 3 (May 1842): 776.

[56] As cited in Leonard I. Sweet, “Millennialism in America: Recent Studies,” Theological Studies 40 (1979): 512.

[57] Ibid., pp. 513.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue