Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 1

Beyond Matriarchy, Beyond Patriarchy

Because Mormons don’t yet have a strong tradition of speculative theology, I want to explain some of my objectives and methods in writing this essay. My chief purpose is to make symbolic connections, to evoke families of images, and to explore theological possibilities. In doing this, I have purposely mixed voices, approaches, and tones to form a circular and mythic mosaic of past, present, and future which still, I hope, moves in a linear direction. And though I make use of biblical scholarship and criticism, I do not intend to prove my conclusions historically; and I do not wish to be read or interpreted dogmatically. In fact, one reason I am so fascinated with the mythic approach is that it is so flexible and nondogmatic. William Irwin Thompson, a cultural historian, observes: “Mythology is not a propositional system of knowledge. Truth is not an ideology. Truth is that which overlights the conflict of opposed ideologies, and the conflict of opposed ideologies is what you get in myth. . . . The truth overlights both ideologies, and no single human institution or single individual can embody the fullness of truth” (1978, 119).

Modern usage imputes to myth the connotations of a false story, the product of a primitive, superstitious mind, without the benefit of science to explain how the world works. History is often characterized as the opposite of myth because history deals in the scientific discovery of verifiable facts and events, while myth is seen merely as the product of imagination. The modern, objectivist world prefers history and often denigrates myth. But each contributes interdependently to our culture and our understanding of the world. Where history attempts to reconstruct the past fact by fact, myth attempts to see the meaning of the facts as they relate to one another, and to the whole fabric of human knowledge and human experience — past, present, and future. History deals largely with cause and effect; myth deals primarily with modes of understanding. To quote Thompson again: “Mythology .. . is interested in paradoxes, opposites, and transformations — the deep structure of consciousness and not the surface of facts and sensory perceptions” (1978, 120).

Objective fact is not unimportant. On the contrary, it is extremely important that hypotheses and theories be tied to reality — to actual experience — lest we construct worldviews of delusion that lead people to deny their real feelings and experience. Myth, then, is not white-washed or fanciful history but an acknowledgment that facts, like salamanders, are slippery things, that objectivity is also a point of view, and that data is usually determined by what individuals perceive. One characteristic of myth is the numerous versions of each story. Each version is important because it reveals something about the perceptions of the individual or culture that produced it, and each must be taken into account in reconstructing our own picture of the “truth.” What follows is, then, my version of the myth.

In Jesus Through the Centuries, Jaroslav Pelikan reminds us that the vitality of Jesus, as the central figure in Western religious experience, depends on the flexibility and fulness of his character. “For each age, the life and teachings of Jesus represented an answer (or, more often, the answer) to the most fundamental questions of human existence and of human destiny” (1985, 2). Similarly, according to Paul Tillich, the revelation of God in Jesus Christ was final and sufficient in the sense that Christ’s nature is expansive enough to include every element necessary for the full revelation of the divine (2:119- 20). This is classical Christian theology in both the Catholic and Protestant traditions. Since God revealed himself “once and for all” in his son Jesus, then Jesus becomes the center of human history and society; he becomes the model or norm for human behavior and the focal point for all meaning in existence. Karl Barth puts this proposition thus:

In Him (Jesus Christ) God reveals Himself to man. In Him man sees and knows God. .. . In Him God’s plan for man is disclosed, God’s judgment on man fulfilled, God’s redemption of man accomplished, God’s gift to man present in fulness, God’s claim and promise to man declared. . . . He is the Word of God in whose truth every thing is disclosed and whose truth cannot be overreached or conditioned by any other word. . . . Except, then, for God Himself, nothing can derive from any other source or look back to any other starting-point (1961, 111).

However, in the past few decades this Christocentric (Christ-centered) view has been seriously challenged. If Jesus Christ is the complete revelation of the divine, some ask, is the white Western male inherently superior and closer to the image of God than any other race or sex? And if Jesus Christ is the model for human behavior, then how can women, minority races, or Third World peoples fully partake of salvation and participate in the Christian life? (Driver 1981)

These are all good questions, but I will focus on one: Christ’s maleness as a revelation of the divine nature. Why did God reveal himself in a male body? Does this affect the status of women? Why didn’t a female goddess work the atonement? Or put in another way, “Can a male Savior save women?” (Ruether 1983, 116)

The revelation of God as male has, historically, been an extremely important buttress of male domination of women. Since Christ was male, only men have been deemed worthy of ecclesiastical and spiritual authority. As recently as 1977, Pope Paul VI justified banning women from priesthood ordination on the grounds that, since Christ was a male, priests — as his representatives — must also be male (Goldenberg 1979, 5; Ruether 1983, 126).

This attitude has led many contemporary feminist theologians to reject Christ as Savior, although not all reject Christianity. At one end of the spectrum, feminist revisionists see much within the Christian church and tradition worth salvaging. In a sense, they have turned the question around and asked, “Can women save a male Savior?” Though many of these women do not accept Christ as the incarnation of God, they do accept him as an important prophetic figure and as a savior of sorts, who treated women with great equality for his time and preached a gospel of love, healing, wholeness, and freedom. Feminist revisionists feel that when all the texts are reexamined and separated from their patriarchal overlays, the essence of the gospel that emerges is liberation from classism, racism, sexism, and every other -ism (Ruether 1983; Moltmann-Wendell 1986; Fiorenza 1979, 139-148; West 1983). This invitation to full humanity is summed up by the apostle Paul: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28).

The revisionists also search both canonical and noncanonical texts for feminine images of the divine and historical evidence of women in priestly roles. Among other important finds, Elaine Pagels has discovered evidence of a God the Mother in the gnostic tradition (1979, 107-19), and Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza has found textual evidence of early Christian women serving as apostles and bishops (1979, 84-92).

At the other end of the spectrum are feminists who feel that Christianity is so thoroughly saturated with sexism and patriarchy that no reform is possible. They ask for nothing less than the death of both a Father God and his Son (Daly 1979, Goldenberg 1979). For such radical feminists, rejecting Christ as God incarnate is not enough. They also reject him as prophet:

Jesus Christ cannot symbolize the liberation of women. A culture that maintains a masculine image for its highest divinity cannot allow its women to experience themselves as the equals of its men. In order to develop a theology of women’s liberation, feminists have to leave Christ and Bible behind them. Women have to stop denying the sexism that lies at the root of the Jewish and Christian religions (Goldenberg 1979, 22).

In Mormonism, feminist issues rarely center on Christ. (The question most often posed is: How can Christ, as male, be a role model for women?) Instead, the battle between patriarchy and matriarchy centers on the relative status of Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother. Is she his subordinate or his equal? Also, most feminist research in the Mormon tradition has not been theological but historical, focused on nineteenth-century Mormon women in a much needed attempt both to reclaim a past and to discover possible sources of power for women.

One reason that Church members rarely ask “Why a male Savior?” is that mainstream Mormons seldom think of Jesus Christ as God. He is seen as an elder brother, a mentor, an example of divine love, and a loving Savior, but rarely as God incarnate, that is, possessing the full characteristics of a God before he ever came to earth. Because we Mormons usually do not think of Christ as God, the question of his maleness as a reflection of the divine image does not seem as crucial to us as it does to other Christians. Thus most Mormons would not see the question “Why a male Savior?” as central to questions dealing with God’s nature and personality but rather in terms of role models. And for many Mormon intellectuals, the whole question seems to be irrelevant because they view the idea that Christ is God to be a holdover from Joseph Smith’s early trinitarian views, later contradicted by his discussion in the King Follett discourse of a progressing God.

Personally, I find no comfort in either the feminist rejection of Christ as God or in my own Church’s ambivalence about his status as God and his importance as an object of worship (McConkie 1982, 97-103).

Feminist theology has served to reemphasize present human experience as a basis for understanding scripture and tradition. As Rosemary Radford Ruether points out, the experiential basis for theological interpretation has always been recognized; the real contribution of feminism is to explode the objective/subjective dichotomy:

What have been called the objective sources of theology, scripture and tradition, are themselves codified collections of human experience.

Human experience is the starting point and the ending point of the hermeneutical circle. Codified tradition both reaches back to roots in experience and is constantly renewed or discarded through the test of experience. Received symbols, formulas, and laws are either authenticated or not through their ability to illuminate and interpret experience. Systems of authority try to reverse this relation and make received symbols dictate what can be experienced as well as the interpretation of that which is experienced. In reality, the relation is the opposite. If a symbol does not speak authentically to experience, it becomes dead or must be altered to provide a new meaning (Ruether 1983, 12-13).

The point is that we must rely upon our own experience to understand the meaning of scriptural tradition in our own lives. In a sense, we are each like Joseph in the grove, who realized he must approach God for himself, since the teachers of religion “understood the same passages of scripture so differently as to destroy all confidence in settling the question by an appeal to the Bible” (JS-H2:12).

At a time of crisis in my own life, I experienced the love and power of Jesus Christ in such a way that I cannot reject him as Savior, nor can I be ambiguous about his divinity or his identity as God. On the other hand, I cannot believe that he meant his appearance on earth to reinforce male dominance. In contrast, my own experiences with him have been liberating. And yet, I have not been able to disregard Christ’s maleness or dismiss it as either meaningless or irrelevant. So what does his divine maleness mean? How does it illuminate and relate to the feminine?

Some time ago I began searching for the answers to these questions in the paradoxes of my religion. I see paradox at the heart of existence and the crux of Christianity. We live in a world of polar opposites, where all things are a “compound in one” (2 Ne. 2:11). Both the tension and the union of opposites engenders life on many different levels. In these unions, opposites are not destroyed nor do they lose their individual identities. True union does not remove differences, but balances apparently opposing principles harmoniously: each opposite is valued and proves a corrective to the excesses of the other.

The feminine and masculine are two such opposites. Each principle must be valued independently, and yet each must simultaneously be seen in its relationship with the other. In our mortal state, this is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to do. In Jesus’s words, “No man can serve two masters” (Matt. 6:24), perhaps suggesting that human finitude, at least in its Western manifestation, may be predisposed toward monotheism. Even in cultures where a pantheon of gods exists, there is often a head god and a rivalry among the lesser gods for supremacy. Many feminist theologians, who reject the worship of the Father God, ignore the option of worshipping a Divine Couple and advocate the worship of the Mother Goddess of prehistory.

Though I see much value in goddess worship and feel men and women need access to a feminine deity, most modern goddess worship is flawed by merely attempting to replace patriarchy with matriarchy, which is, in my opinion, equally destructive and sexist. Modern goddess literature sometimes belittles men, who are said to be incapable of equality with the goddess or women, but can only serve as sons and lovers (Goldenberg 1979, 103).

And just as women, in the past, have been seen as the source of all evil, symbolized by Eve in Judeo-Christian literature, men become scapegoats in much extreme feminist literature (Daly 1978). The white Anglo-Saxon upper middle-class man is often seen as the source of all evil, even by moderates such as Ruether (1983, 179-80). The evil female seducers bow off the theological stage and the evil male rapists step forward. Though the devouring vagina and the phallic sword are ancient symbols of male/female conflict, they are by no means obsolete.

Introducing her essay on the problem of women accepting a male savior, Rita Nakashima Brock recounts her experiences with rape victims and ob serves: “Essential to that ancient dominant-submissive rape ritual are the rules that give no power and authority to women except through our relationships of submission to men. In Christianity, are women therefore redeemed and legitimated by our reconciliation to the saving efficacy of a male savior?” (Brock 1985, 56) And in Hartman Rector’s statement to Sonia Johnson, he uses the image of a black widow spider, evoking the time-honored spectre of the devouring female (Gottlieb and Wiley 1984, 212). So the battle between patriarchy and matriarchy goes on.

How can we get beyond the point where each side thinks of the other as an enemy? For me, the answer rests in resolving the tension between my traditional views of the Fall and Redemption and my radical views about the nature of God and the cosmos. Though I believe that Christ was God incarnate and a revelation of the divine, I do not believe that his appearance on the earth was a complete, “once and for all” revelation of God and of the divine nature. And though I see Christ’s sacrificial act on the cross at the center of human existence and high point of history, I also see him encompassed about by the feminine as the defining points of existence. The feminine marks the boundaries at the far corners of my theological universe. In sum, for me, it is inevitable that there should be a revelation of the goddess, the consort of Christ, who guards the portals of life, the gates at the beginning and the end of time.

To explain what I mean by these abstractions, let me use a model adapted from Jungian psychology. Jung and his followers, Erich Neumann in particular, describe four stages of human development connected with chronological development, though not every person progresses through the successive stages in the same way and at the same rate. In fact, many people may never emerge from the second stage, while others remain fixed in the third. And even those who reach the fourth stage are not fully developed individuals, for psychic growth is an ongoing, lifetime process.

The first stage is associated with the prenatal or infancy period of human development. Here, according to Ann Ulanov, a Jungian analyst and theologian, “The ego exists in an undifferentiated wholeness; there is no distinction between inner and outer worlds, nor between image, object, and affect, nor between subject and object. The ego feels it is magically at one with its environment and with all of reality as a totality” (1971, 67). The symbol of this stage is the uroboros, the mythical tail-eating serpent, which “represents circular containment and wholeness” (Ulanov 1971, 67).

In the second stage, called matriarchal by Erich Neumann who connects this phase with early childhood, the ego sees the mother as the source of all life; therefore the Great Mother prevails as archetype of the unconscious individual (Neumann 1954, 39). Creation myths, which typically separate the world into opposites, are often interpreted in terms of the birth of the ego associated with this phase. Though the ego begins to differentiate between itself and the “other” at this stage, it always does so in relation to its mother. Hence, males and females learn to relate in fundamentally different ways. The male’s primary mode of relationship depends on differentiation and discrimination, since he sees himself as distinct from his mother, as like to unlike. In contrast, the female’s primary mode of relationship is identification and relatedness, since she sees herself as like to like in her relationship with her mother. Thus, Ulanov extrapolates, the female’s “ego development takes place not in opposition to but in relation to her unconscious” (1971, 244).

Neumann labels the third stage patriarchal, connected with the period of puberty (1954, 408). In ancient or primitive societies, this stage is memorialized by initiation rites in which the boy is separated from the world of women and brought into the ranks of the men. The girl also undergoes initiation rites to bring her into full status as an adult woman. Myth represents this stage by the loss of Eden through the Fall. Eating of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil represents adult consciousness, which distinguishes fully between opposites: inner and outer, subject and object, and right and wrong. According to Ulanov: “When the transition to this stage is successfully completed, the archetype of the Great Father becomes the sovereign deity and determines the values and goals of life. Consciousness, rationality, will power, self-discipline, adaption to the demands of external reality, and a sense of individual responsibility become important” (1971, 69). Moreover, in this stage, anything feminine is likely to be rejected as inferior: “The values of the masculine are endorsed at the expense of feminine values; the principle of spirit is seen as opposed to earth; order and definition are seen as superior to creative fertility, commandments and obedience are valued over the virtues of acceptance and forgiveness, and becoming is seen as better than ‘just being'” (1971, 69).

The final “integrative” stage requires a reconciliation of opposites, both internally within the self and externally in the self’s relations with the outer world and other people. In particular, all elements of the feminine which were rejected and repressed in the patriarchal phase must be reclaimed, both inwardly and outwardly. The integrative stage emphasizes unity and wholeness, then, but not the undifferentiated wholeness of the first and second stages. Rather, all parts of the whole are distinguished and recognized but are not perceived as rivals, as in the patriarchal stage. Instead, the parts are valued for their own unique contribution to the harmonious balance of the whole. It is a circling back to a wholeness lost, but a wholeness with new meaning. In T. S. Eliot’s words:

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time (1971, 145).

The self, having gained strength by the ego differentiation and self definition of the preceding stage, must now see the limitations of individual ego and return to the unconscious which it has rejected. As Ulanov puts it: “Whereas in the patriarchal phase the power of being was experienced in terms of the ego’s personal goals and meanings, in the integrative phase the power of being is experienced symbolically in the mystery beyond the ego and the ego’s powers” (1971,72).

The integrative phase is the most demanding because it cannot be achieved in isolation but must be worked out in relationship to the outer self, the inner self, the outer reality, the inner reality, other people, and God. But paradoxically, only in this enmeshed stage does the individual become a separate, individual entity. Here a woman and a man fully represent more than their sexual or social roles; they are distinct individuals, “as differentiated from having only collective identity as members of a certain family, or group, or nation” (Ulanov 1971, 71). Jung called this process of integration “individuation,” the process by which we become fully our best selves. In religious terms, this process could be compared with sanctification.

These four stages of human development can serve as a spiritual model not only to explain the development of the individual in mortality, but also the purification of the individual as she or he makes the cosmic journey of existence from an intelligence to a resurrected and glorified being.

Adapting this model to an eternal timeline, I connect the first or prenatal stage with our existence as intelligences, the formative period of our development about which we have the least knowledge. Though most Mormon theologians have emphasized the independent nature of intelligence, the actual statements we have on the subject focus on the uncreated nature of intelligence rather than on its complete separateness from God. Joseph Smith’s curious statement that our minds or intelligences were “coequal with God himself” (Ehat 1980, 359) suggests that, as intelligences, we may have been connected in some way with our divine parents. This is similar to the undifferentiated wholeness of the Jungian model. Doctrine and Covenants 93:23 states that we “were also in the beginning with the Father; that which is Spirit, even the Spirit of truth,” and in the 29 August 1857 edition of The Mormon, editor John Taylor suggested that we were once somehow part of the mind of God, “struck from the fire of his eternal blaze, and brought forth in the midst of eternal burnings” (in Andrus 1968, 179).

The matriarchal or second stage, I connect with the period prior to mortality. Again, popular notions of this stage derive from Mormon folklore and speculation; we actually know little about it. However, for our model, the significance of this stage is its domination by the Great Mother figure. In the LDS tradition, we most often associate a Heavenly Mother with the pre existence. In the hymn, “O My Father,” Eliza R. Snow implies that her knowledge about her Heavenly Mother is intuited from the forgotten experience of a prenatal world. Hugh Nibley points out in his discussion of the early Christian poem “The Pearl” that it is the Queen or Mother who is the first and last to embrace the departing hero as he leaves his heavenly home and begins his sojourn in the fallen world (1975, 272).

But is there any corroborative evidence that this stage was connected with a Great Goddess? If so, who was she? What was her function and relation to us? And why was she superseded by the Father God?

Scholars in the fields of religion, mythology, and archaeology currently debate whether there actually ever was a period of history or prehistory in which the Great Goddess was generally worshipped to the exclusion of a male deity. Some archaeological evidence, in the form of cave drawings, goddess figures, and structures built in the shape of the goddess or her life-giving womb, seems to support the notion that in prehistoric times a goddess was looked to as the source of all life and the obvious object of worship (Neumann 1963; Stone 1976; Dames 1976; Gimbutas 1974; Thompson 1981). However, lack of written documents renders all such conclusions speculative.

To the archaeological evidence may be added the evidence found in ancient mythologies. Though the mythologies from the Near Eastern world depict pantheons of gods in which a male deity is almost always supreme, the goddesses are still independent and powerful, often vying with the gods for power. In fact, most creation stories from these cultures depict a strong theme of matriarchal-patriarchal struggles. “It is as though the writers [of the creation myths] believed that civilization could not begin or be sustained until the feminine, as a dominant religious power, had been mastered and domesticated” (Phillips 1984, 4). For example, in the Mesopotamian creation story, Enuma elish, the warrior-god Marduk first must kill “Tiamat the dragon-mother of all creation,” and then “he creates the world by splitting her carcass into earth and sky; she herself becomes the primordial matter [i.e., matter or mother] of the universe” (Phillips 1984, 5). The Greek poet Hesiod records a similar struggle in his version of the creation story, the Theogony, which reads almost like an anti-feminist tract. This misogynist view, which continued throughout the Hellenic civilization, profoundly affected the early Christian church and, therefore, views of women throughout the Christian epoch (Phipps 1973, 77-94).

Many scholars feel that the struggle between the male and female deities in the Near Eastern mythologies represents the historical struggle between older civilizations dominated by the worship of the Great Mother and the rising new powers which favored male gods. The domination of the male deities over their female counterparts would then symbolize the actual historical conquest of one culture over another (Thompson 1981; Morford and Lenardon 1985, 41). But if there was a period, premortal or otherwise, where a goddess was worshipped, who was she?

Although names and places differ, there is a continuity among the goddess’ varying images. For example, in Greek mythology, though Hera, Demeter, Aphrodite, and Artemis all have distinct personalities and functions, each god dess is also seen at times, both in art and literature, as a Mother Goddess figure. Recently, several scholars have also associated Eve, the only female in the Judeo-Christian creation story, with the Mother Goddess of other ancient religions, since the pattern of her story parallels the accounts of other goddesses of the Near East. Furthermore, the name Eve means, according to Genesis 3:20, “the mother of all living.” This is the title most commonly associated with the Great Mother Goddess, and Nibley points out that in the Egyptian rituals all the goddesses went by this title at one time or another (1975, 166). Moreover, in Sumerian mythology there is a connection between the title “mother of all living” and the title “lady of the rib” because of a similarity of word sounds. Both of these titles were used to refer to a goddess who healed the rib of the God of wisdom. According to Sumerian scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, “In Sumerian literature, therefore, ‘the lady of the rib’ came to be identified with ‘the lady who makes live’ through what may be termed a play of words. It was this, one of the most ancient of literary puns, which was carried over and perpetuated in the Biblical paradise story” (1961, 103).

Though Judeo-Christian tradition depicts Eve as merely mortal, Isaac Kikawada believes that “behind the character of Eve was probably hidden the figure of the creatress or mother Goddess” (1972, 34). John A. Phillips concurs with this supposition and adds: “The story of Eve is also the story of the displacing of the Goddess whose name is taken from a form of the Hebrew verb ‘to be’ by the masculine God, Yahweh, whose name has the same derivation. We cannot understand the history of Eve without seeing her as a deposed Creator-Goddess, and indeed, in some sense as creation itself” (1984, 3; see also Millet 1970, 52; Asche 1976, 16-17; Heller 1958, 655; and MacDonald’s Eve figure in his 1895 Lilith).

Despite its elevated associations, many feminists have objected to Eve’s name since it was given her by Adam. Their argument is that the act of naming gives the namer authority to define and limit the object named (Daly 1973, 8). And, of course, in the ancient Hebrew culture, as well as in other Near Eastern cultures, people believed that even knowing the name of something gave the knower power over the object named. Jacob wrestling with the angel and Odysseus’ conflict with the Cyclops illustrate the prevalence of this concept. Traditionally, scholars have linked Adam’s dominion over the animals with his power to give them names. The same interpretation can be signed to his naming of Eve and may lie at the root of much of men’s domination of women. By keeping the power of words and history in their control men have been able to define what women are and can be.

Phyllis Trible acknowledges this argument but objects to a misinterpretation of the text. The formula used by Adam to name the animals is different than that used to address Eve: “In calling the animals by name, ‘adham establishes supremacy over them and fails to find a fit helper. In calling woman, ‘adham does not name her and does find in her a counterpart. Female and male are equal sexes. Neither has authority over the other” (1979, 77). Moreover, other traditions present alternative descriptions of this event. For example, in the Gnostic text “On the Origin of the World,” Adam gives Eve her name not as an act of domination but in recognition of her superiority:

After the day of rest, Sophia sent Zoe, her daughter, who is called “Eve (of life)” as an instructor to raise up Adam, in whom there was no soul, so that those whom he would beget might become vessels of the light. [When] Eve saw her co-likeness cast down, she pitied him, and she said, “Adam, live! Rise up on the earth!” Immediately her word became a deed. For when Adam rose up, immediately he opened his eyes. When he saw her, he said, “You will be called ‘the mother of the living’ because you are the one who gave me life” (Bethge and Wintermute 1977, 173).

The naming of Eve is not the only part of the Hebrew creation story that troubles feminists. To them, the whole story is merely an aetiological myth, a story used to justify men’s domination of women. For this reason many feminists feel that the story should be rejected along with the concepts of the Father God and Christ (Millett 1970, 51-54). Recognizing the power of symbol and the need for myth in communicating ideas, some women have turned, instead, to the figure of Lilith (Plaskow 1979). According to Jewish legend, Lilith, Adam’s first wife, came before Eve. Adam and Lilith had not been together very long before they began arguing — each refusing to take what they regarded as the inferior position in the sex act. Finally, when Adam tried to force Lilith beneath him, she uttered the ineffable name of God and disappeared. To fill her place, God then created Eve (Patai 1980, 407-8).

For my own part, though I find the character of Lilith fascinating, my sympathies rest with Eve. For me she is the central figure in the Garden of Eden story (Toscano 1985, 21-23). Phyllis Trible, who also takes this view, maintains that Eve is not the deceptive temptress of the traditional interpretation, but rather an “intelligent, sensitive, and ingenious” woman who weighs carefully the choice before her and then acts out of a desire for wisdom (1979, 79). Trible’s interpretation lacks only a good reason why Eve’s choice is commendable rather than simply a disastrous sin.

Mormon theology supplies this answer: the Fall was necessary for the development of the souls of women and men. Obtaining physical bodies is part of God’s plan, a step toward obtaining the power and likeness of God. However, Mormonism is not alone in asserting the positive aspects of the Fall. Many Enlightenment thinkers interpreted the Eden story in this way. For them, the Fall was also a necessarium peccatum (a necessary sin) and a felix culpa (a happy fault). The Fall was a step forward in human progress, since it took humankind “from blissful ignorance to risky but mature human knowledge, from animal instinct to human reason” (Phillips 1984, 78).

While Mormonism has treated Eve much more positively than has Christianity in general, she is still seen as deserving a position subordinate to Adam. For example, in the Articles of Faith, Apostle James E. Talmage, while insisting that we owe gratitude to our first parents for the chance to experience mortality, still agrees with Paul that “Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression” (1890, 65). For BYU religion professor Rodney Turner, the story of the Fall shows why men have a rightful stewardship over women. He reasons that, whereas before the Fall men and women both had direct access to God, after the Fall men stood between God and women as their head, to lead them back to God (1972, 52-53). Strangely, Turner does not expect the celestial kingdom to rectify this fallen order: “And Woman, although a reigning majesty, will nevertheless continue to acknowledge the Priesthood of her divine companion even as he continues to obey the Gods who made his own exaltation possible” (1972, 311). In like manner, I have heard other Mormons argue that since the Fall itself is not evil, then Eve’s servitude is not simply a punishment or result of sin, but a reaffirmation of her eternally subordinate status which she overstepped when she took the initiative in eating the fruit.

Other puzzling questions emerge in the common Mormon argument over whether Adam and Eve’s action should be called a “sin” or a “transgression”— a distinction Joseph Fielding Smith endorsed to emphasize the necessary nature of the Fall (1:112). If mortality is good, then why do Adam and Eve commit a sin in bringing it about? Why did God forbid them to eat of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil if that was the only way to introduce them into mortality, a necessary step in eternal progression? It seems at first there is no way out of this dilemma. Either Adam and Eve (and especially Eve) were bad, or God was bad.

Orthodox Christianity has, of course, chosen to put the blame on Eve and women in general. Other so-called “heretical” early Christian sects, such as the Gnostics and Manichaeans, chose to see Adam and Eve as Prometheus figures who dared to defy the jealous Old Testament God who wished to keep humanity enslaved in ignorance. Mormonism tends to avoid the question by calling the Fall a “transgression” rather than a “sin.” We do this perhaps because we are uncomfortable with the idea that we live in a world where choices between good and evil are not clearly defined.

In my own view, the answer to this dilemma lies in the paradoxical aspects of the creation story itself. In the garden are two trees: not the Tree of Good and the Tree of Evil, but the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. These trees signal to us that for Adam and Eve, as well as for us, the choice between the trees is a complex one. Part of that complexity may revolve around the function of Eve as the Mother Goddess. As “the Mother of All Living” Eve must be regarded as in some ways Adam’s parent as well as his mate.

Mother Eve’s virtue and greatness, in my view, rest in her ability to perceive paradox and to see that growth comes about through distinguishing between opposites. The Garden of Eden was not a place of opposites. It was a place of maternal wholeness, a state of protection in which Eve’s children and also Adam could have all their needs met. But the child grows into a healthy adult only by becoming independent. If the mother fails to let the child go at the appropriate time, then she becomes a devouring mother instead of a nurturing one. It is really up to the mother to end the matriarchal stage and lead the child into its next phase of development — the patriarchal stage.

If distinguishing opposites is one of the main characteristics of the patriarchal stage, then Eve’s choice can be interpreted as noble rather than impulsive. For she, as “the mother of all living,” saw that the life of all her children could come about only through her death. Consequently, she put her life on the altar. She put to death her eternal life in the Garden of Eden to bring about their mortal life on earth. She clearly saw that “there was no other way.”

Nevertheless, Eve’s action, though noble, was still a sin because she had disobeyed God’s commandment; she ate when she had been forbidden to do so. But what about God’s part in this crime? Is he also culpable or at least at fault in some way? Why had he made it a sin to do that which was necessary for the progression of his children? Again, the answer is not a simple one. It rests on a statement made by Joseph Smith: “That which is wrong under one circumstance, may be and often is, right under another. God said thou shalt not kill, at another time he said thou shalt utterly destroy” (Jessee 1984, 508).

God may indeed have intended for Adam and Eve to eat the fruit to bring about mortality, but at another time or under another circumstance. Perhaps he wanted them to approach him with their dilemma and ask how they could fulfill all of his commandments without eating the fruit. And perhaps he planned to grant them the fruit as a result of that request. Might the sin in the garden be not the fruit, but the failure to seek it from the hand of God?

If so, this interpretation sheds light on the nature of Satan’s crime as well. His sin was to usurp God’s prerogative to initiate Adam and Eve into the lone and dreary world. He was playing God. And in fact on closer examination most of what Satan tells Eve is true; for when Adam and Eve eat the fruit, the Lord himself repeats Satan’s statement that the man and the woman have now become as gods, “to know good and evil” (Gen. 3:22).

So Eve was deceived, but not by false ideas. Rather, she was deceived because she mistook Satan for a messenger of God. The point is that the truth of revelation consists not just in its content, but in its source as well.

Eve’s choice to eat the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, then, must be seen as a conscious and deliberate act of self-sacrifice. For she knew that her choice constituted acceptance of the law of opposites: that pleasure could only be known through pain, health through sickness, and life through death, as she indicates in the temple version of the story. Symbolically, her choice was a yielding of matriarchal wholeness to patriarchal differentiation.

Seen in this light, Eve’s subordination to Adam was not so much a prescription of what should be but a description of what would be. In other words, God’s statement is not that the husband ought to rule over his wife, but that he would rule over her in the patriarchal stage. Phyllis Trible comments:

The divine speeches to the serpent, the woman, and the man are not commands for structuring life. To the contrary, they show how intolerable existence has become as it stands between creation and redemption. . . . Yet, according to God, she [Eve] still yearns for the original unity of male and female . . . however, union is no more, one flesh is split. The man will not reciprocate the woman’s desire, instead he will rule over her. His supremacy is neither a divine right nor a male prerogative. Her subordination is neither a divine decree nor the female destiny. Both their positions result from shared disobedience. God describes this consequence but does not prescribe it as punishment (1978, 123, 128).

When Eve decides to bring about mortality, she does so at the greatest expense to herself, not to Adam. It is true that, in the temple version, Adam also sacrifices by willingly following her (Turner 1972, 309; Talmage 1899, 69-70). But Eve takes the blame for their action, as well as the subordinate status. Her action can be illumined by comparing it to the ancient ritual called the humiliation of the king, which was part of the rites of the ancient Mesopotamian New Year Festival. In this rite, the king was stripped of his kingly vestments and power, beaten, and made to confess his responsibility for the sins of his people and then to wander the streets as a beggar. Finally, he, or a substitute for him, was put to death to fertilize the earth and renew the life of his kingdom and people (Engnell 1967, 33-35, 66-67). Though this ritual most often involved the death of a king or a male god, reversals were also possible. Mary Renault, in her novel The Bull From the Sea (1962), interprets the story of Theseus in this way, when his wife Hippolyta dies in the place of her husband, as a substitute “king.”

Moreover, several Near Eastern goddesses enact the pattern of the humiliation of the king or descent of the god. Inanna, an ancient Sumerian goddess, who was queen of heaven and also of the city of Uruk, yielded her royal and sovereign power to her husband, Dumuzi, laying aside all her priestly offices and stripping herself of all her vestments of power so that she could penetrate the underworld and learn its mysteries. Once there, she was pronounced guilty and struck dead by Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld, who hung her corpse “from a hook [or nail] from the wall” (Wolkstein and Kramer 1983, 60). After hanging there for three days and three nights, she was raised to life again by the intercession of the god of wisdom and other deities. She ascended to heaven, her power over life and death acknowledged by the Sumerians, who looked to her as a fertility goddess, in control of all life cycles and seasons.

In the well-known Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone, Persephone, another fertility goddess, descended to the underworld; and in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (Athanassakis 1976) she functions as a savior goddess. Though her descent to Hades introduced death and the seasons into what had been a state of paradise, her return to life and to her mother Demeter brought renewal. This myth is believed to be the subject of the ancient Eleusinian mysteries, which presumably gave initiates hope for an idyllic afterlife.

Isis, an Egyptian goddess, also functioned as a savior goddess, both in myth through her descent to save Osiris, and in cult practice through her promise of comfort and immortality to initiates (Bleeker 1963).

Eve’s story parallels these goddesses’ in intriguing ways. Like Isis, Eve acted as savior to bring life to others. Like Persephone, Eve’s descent into mortality brought about the changing cycle of life and death and brought an end to the timeless state of paradisiacal bliss. And like Inanna, Eve made her pilgrimage into the world of darkness to acquire knowledge both of good and of evil. In their quests, both Eve and Inanna turn their authority over to their husbands, who then rule over them.

In his Lectures on Genesis Martin Luther talks about the fate of Eve and all womankind who are “under the power of the husband.” He compares their subjugated state to “a nail driven into the wall,” fixed, immovable, and hemmed in by the demands of men, so that their sphere of influence is confined to the home (1:202). Though Luther does not seem to be aware of the power of the symbol he has chosen, I see a connection with the goddess Inanna, whose corpse hung from the nail on the wall. Isaiah 22:23 and Ezra 9:8 represent God’s grace, eventually manifest in the person of Jesus Christ, as a “nail in a sure place” on whom hangs “all the glory of his father’s house.” According to the Interpreter’s Bible, the “nail” was “a wooden peg which was driven into the wall and used for hanging domestic utensils” or keys (5:293). The same Hebrew word can also refer to a tent peg and appears in Isaiah 54:2: “Lengthen thy cords and strengthen thy stakes,” from which we derive our term “stake.”

Eve can be seen as the counterpart and parallel to Christ. For Eve, too, is a “nail in a sure place,” the glory of her mother’s house. Just as Eve sacrificed herself and was humiliated to bring her children into mortal life, so Christ sacrificed his life and was humiliated to bring his children into eternal life. As Eve’s death was necessary to bring an end to the matriarchal stage, so Christ’s death was necessary to bring an end to the patriarchal stage. Angela West comes to a similar conclusion:

Christ became Son and not Daughter because the symbol of female power, the god dess, had long since been done to death and needed no further humiliation; and because the daughters of Eve are always and everywhere being brought low through childbearing (or barrenness) and subordinated in the name of the patriarchal God. But in the person of Jesus Christ, God denies the godhead as patriarchal power, and reveals Godself in humanity, in the helpless infant, in the helpless crucified human being (1983, 89).

I have already implied that mortality can be compared to the third or patriarchal stage of the Jungian model. Seen in this larger perspective, patriarchy becomes a little easier to understand and accept as just one act in a larger drama, a necessary step in the development of the individual personality and of the human race.

However, I do not mean to justify all the abuses of the feminine that have occurred in the previous millennia. Nor am I advocating we do nothing to correct them. Quite the contrary. Any power system not held in check by a loyal opposition tends quickly to become oppressive. However, though abuses are rampant, we should not refuse to see the necessity and good of the patriarchal stage. This necessity is illuminated for us by the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ, who is the revelation of the Father figure for us.

Though Christ’s mission was parallel to Eve’s, it was not identical to it. Where Eve’s mission occurred at the end of the matriarchal stage, Christ’s mission occurred in the middle of the patriarchal — in the “meridian of time.” And though his mission was meant, ultimately, to doom patriarchal authority, Christ did not put an abrupt end to these power systems as many had expected the promised Messiah to do. The reason for this is important. Christ’s first coming was to define the true purpose of the patriarchal stage as a probationary state in which we must make distinctions, differentiate between opposites, and use our knowledge of good and evil to choose the way of liberty and life rather than the way of oppression and death (2 Ne. 2:27).

The symbol of Christ’s coming into the world is the cross, represented at times by the two-edged sword which can divide asunder both “joint and marrow” (D&C 6:2). Christ, as the word made flesh, is also the sword of God’s justice, which “hangs over us” (3 Ne. 20:20). But the purpose of the sword is paradoxical. For though God’s justice was meant for us, Christ was wounded for our sakes. The sword pierced his side. Thus, the sword which guards the Tree of Life becomes the iron rod that leads believers to the fruit of that tree. The sword is two-edged because it can both destroy life to administer death and destroy death to administer life. Those who allow themselves to be pierced by the word of God, which is his sword (Rev. 2:16), will receive new life, but those who harden their hearts against God’s word will cut themselves off.

Christ’s mission, like the double-edged sword, is paradoxical. For while he came to show that the true importance of the patriarchal function was to make distinctions and choose, the choice he advocated was the denial of goodness strictly in patriarchal terms and the affirmation of goodness as it exists in something other than ourselves. Angela West comments on the irony of this paradox:

[The story of Christ is] the only scandal that patriarchy couldn’t dare to contemplate; the story of God who de-divinised Godself and became a human historical male who turned out to be a complete political failure. It presents God as the ultimate contradiction to the worship of male power, and mocks all gods and goddesses, who are nothing more than this.

In order to show men, and men in particular, that God was not made in the image of man, God became a man, and [when] that manhood was crucified, patriarchal pretensions were put to death. . . . Christ died on the cross cursed by the patriarchal law, and the law of patriarchy is thus revealed as curse and cursed (1983, 88-89).

The very act of God’s coming to earth as a human being is a statement about the need we all have to see the good in our opposites. Though Christ was the Father of Heaven and Earth, he made of himself a Son to bring about the Father’s will. Though Christ was a male, he assumed the role of a female to give birth to a new creation through the blood he shed in Gethsemane and on the cross. Though Christ was creator, he became part of the creation to show the inseparability of the two. Though Christ was God, he became human to reveal that true love is in relationship. And though Christ was above all things, he descended below all things “that he might be in and through all things, the light of truth” (D&C 88:6).

The patriarchal stage is important. It allows the ego to develop by making it aware of contrasts and choices. But the important choice of the patriarchal stage is to deny the self-sufficiency of the ego and to move out of that stage into the integrative phase of wholeness, where all that was lost is reclaimed, particularly the feminine. The ego sees its own limitations by first recognizing itself as separate from God, the primary “other,” and next by recognizing its own insufficiency — recognizing that it is unable to rescue itself from its own egocentricity and its own narrow categories of perception. To be saved and transcend its limitations, the ego must deny its self-sufficiency and accept what is held in trust for it by God. Once this happens, the self is prepared to begin the process of individuation in earnest.

However, this is not easy to do because it means that the individual has to move beyond “the safety of patriarchal standards” (Ulanov 1971, 70) and risk uncertainty and personal pain. For men, the main obstacle is overcoming the fear that this step is really a regression into the power of the matriarchal and the undifferentiated unconscious. Moreover, it is difficult for men to give up their status in a patriarchal system that provides personal comfort and power. Women also can be fixed in the patriarchal structure, often because they are prisoners of a world view which denies them power to see themselves as anything but subordinates. There is safety in the status quo. Moreover, even patriarchal systems have matriarchal substrata, which afford women status and the comfort of feeling that they are the “real power behind the throne.” Another danger for women is fear of freedom, which may precipitate them into a safe matriarchal structure which values the feminine at the expense of the masculine (Ulanov 1971, 244-46).

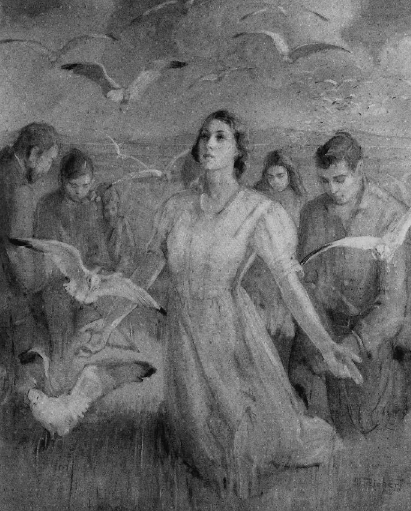

It takes a heroic leap to get beyond matriarchy and beyond patriarchy to a stage of integration and individuation. And, in fact, many of our fairy tales and hero myths describe the rescue mission involved in this process. Best known are the stories of the prince who rescues the princess from the dragon or the tower, but equally important are the stories of the maiden who rescues the prince from the spell of the witch or sorcerer who keeps him in bondage. For us, the point of these stories is that we must each rely on the other for the power to develop into full personhood. When women acknowledge the good in men, men can be freed from the fear of the devouring feminine; when men acknowledge the power in women, women can be freed from subordination to the patriarchy.

The controlling deity for the integrative stage is neither the Great Mother nor the Great Father, but the Divine Couple, united in a marital embrace. I take this image from ancient myth and art, where the hieros gamos (sacred marriage) was an important part of Near Eastern culture for at least 2,000 years (Kramer 1969, 49). Behind this ritual lay the concept that the sexual union of a god and goddess, sometimes a sky god and an earth goddess, would insure the fertility of land, beasts, and humans and the flourishing of civilization. The love stories of such gods as Isis and Osiris, Inanna and Dumuzi, Ishtar and Tammuz, and Hera and Zeus are no doubt related to this belief. As a variation on the ritual, a god could marry a mortal woman, usually a queen or priestess, who, as a representative of the goddess, could assure the fecundity of the entire kingdom. Or a love or fertility goddess would marry a king or priest to bring well-being to his land and people. In a third variation, a king and queen or priest and priestess could ritually reenact the marriage rite as representatives of the divine couple.

Many lead plaques, engraved with couples in sexual poses, have been found in Near Eastern temple sites. According to Elizabeth Williams Forte, “Such scenes are considered representations of the cult of the sacred marriage, which took place annually in each Mesopotamian city” (Wolkstein and Kramer 1983, 187). Though the scenes are obviously erotic, the positioning of the arms and legs and the intertwining of the god and goddess is such that the scenes are not simply sexual, but ritual as well. The impression is that of a ritual embrace, which sacralizes the sex act (Nibley 1975, 241).

Religious tradition holds that the Israelites totally rejected such fertility rites. In the Old Testament, the Yahwist prophets denounced such practices as pagan and an abomination in the sight of God, repeatedly warning the children of Israel to abandon the worship of Asherah/Astarte and to forsake her high places.

However, in this century, some scholars of the myth-ritual school suggest that there may have been legitimate Hebrew rituals to celebrate the marriage of Yahweh and his consort during certain periods of Israel’s history (Hooke 1958, 176-91). Though this school of interpretation is not currently in vogue, the rise of feminist theology in the last few years has resulted in renewed interest in the sacred marriage rites among the Hebrews. For example, Savina J. Teubal explores this ritual in some depth in Sarah the Priestess (1984). An ambitious and thorough analysis of the influence of the Hebrew goddess and her marriage to Yahweh on Judaism is Raphael Patai’s The Hebrew Goddess. He there demonstrates how a feminine divinity has always been a part, though admittedly a hidden part, of the religion of Israel, thus answering, in Judaism, the need for the loving and mothering aspects of deity (1967, 258).

Patai also shows how a feminine image of deity has been viewed as the wife of God, whether it be in the form of a union between God and Wisdom, God and his Shekhina (spirit), God and the Queen Matronit of Kabbalism, or God and his Bride, the Sabbath. Perhaps the most striking image of the union of Israel’s God with the feminine is seen in the Holy of Holies, itself. Patai asserts that the Ark of the Covenant, the holiest object in the temple and the center for legitimate worship, contained images of the sacred marriage:

In the beginning . . . two images, or slabs of stone, were contained in the Ark, representing Yahweh and his consort. . . . The idea slowly gained ground that the one and only God comprised two aspects, a male and a female one, and that the Cherubim in the Holy of Holies of the Second Temple were the symbolic representation of these two divine virtues or powers. This was followed by a new development, in Talmudic times, when the male Cherub was considered as a symbol of God, while the female Cherub, held in embrace by him, stood for the personified Community of Israel (1967, 97-98).

So we come again to the image of the divine couple in a marital embrace. The image of the sacred marriage is not only important historically but can be projected into the future as well, since the image is used in Judeo-Christian eschatological literature to represent the promised revival of the marriage relationship of Yahweh and the community of Israel and the marriage of Christ to the church. In both instances, the marriage symbolizes the time, after tribulation and judgment, when repentant Israel or the church returns to God, her husband.

Bible scholar Joachim Jeremias points out that in the rabbinic literature the “marriage time” is often associated with the Messianic period of peace and feasting (in Taylor 1953, 88). The rabbis took this idea, no doubt, from the prophets who often use marriage language to describe the relationship between Yahweh and Israel (i.e., Isa. 54:5; Jer. 3:14, 31:32; and Hosea 2:19-20). Though Israel is often rebuked as an errant wife, in the Messianic period she will be pure and magnificent, a bride adorned with jewels (Isa. 61:10). And the Lord will no longer look upon her with disfavor, but “as the bridegroom rejoiceth over the bride, so shall thy God rejoice over thee” (Isa. 62:5).

All four Gospel writers, as well as the writer of the book of Revelation, use the bridegroom symbol in connection with Christ. Vincent Taylor, a biblical scholar, asserts that the use of such imagery shows Christ’s “Messianic consciousness, and especially His close relationships with His community” (1953, 88). This argument appears warranted by the bridal imagery in the book of Revelation:

And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of Heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.

And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God (21:2-3).

Raphael Patai, although a Jewish scholar, even includes this passage in his book The Messiah Texts, because the author of Revelation who is Christian nevertheless “described the heavenly Jerusalem in Jewish apocalyptic-Aggadic terms” (1979, 200).

In the New Testament, as in the Old, the bridal imagery is connected with an eschatological end period. This is especially evident in the two marriage parables found in Matthew 22 and 25. The kingdom of heaven is compared to ten virgins, who are awaiting the arrival of the bridegroom. Only virgins with oil in their lamps may enter the marriage feast when the bridegroom finally arrives. The listener is then admonished: “Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son of man cometh” (Matt. 25:13). Earlier in Matthew 22, guests at the marriage feast of the king’s son must have a wedding garment. Revelation 19 almost seems to be a commentary on the parable, for we are told that the “fine linen is the righteousness of the saints” and “Blessed are they which are called unto the marriage supper of the Lamb” (Rev. 19:8-9). Looking forward to the marriage of the Lamb is, therefore, synonymous with looking forward to the second coming of Christ.

This is also true of LDS scripture, in particular the Doctrine and Covenants, where the bridal imagery is used a number of times in connection with the purification of Zion and the second coming of Christ. Doctrine and Covenants 88:92 predicts the coming of the bridegroom during a period of tribulation and judgment, in language similar to that found in Revelation: “And angels shall fly through the midst of heaven, crying with a loud voice, sounding the trump of God, saying: Prepare ye, prepare ye, O inhabitants of the earth; for the judgment of our God is come. Behold, and lo, the Bridegroom cometh; go ye out to meet him” (D&C 88:92; cf. D&C 133:10, 19). As in the New Testament, the Doctrine and Covenants bridegroom image is linked to the marriage supper: “Yea, a voice crying — Prepare ye the way of the Lord, pre pare ye the supper of the Lamb, make ready for the Bridegroom” (D&C 65:3; cf. D&C 58:8-11). The Doctrine and Covenants also repeats the symbolism of the ten virgins, who, as representatives of the community of Israel, are warned to prepare for the coming of the bridegroom: “Wherefore, be faithful, praying always, having your lamps trimmed and burning, and oil with you, that you may be ready at the coming of the Bridegroom” (D&C 33:17).

Although the bridegroom image is familiar, we seldom focus on its implication for the place of the feminine. Viewing the second coming as a marriage means seeing the ushering in of the millennial kingdom as a union of opposites and a reaffirmation of the values of the feminine, for the marriage of the Lamb to the Bride implies the elevation of a female to the status of a divinity. Some scholars argue the opposite — that the symbol of the marriage of Christ is, in fact, a reaffirmation of patriarchal marriage where the male rules, since Christ’s bride is his creation, the church, who must always be subordinate to him (Ruether 1983, 141; Eph. 5:22-25).

But there are other scriptures and traditions that do not speak of the messianic marriage time in these terms. The writer of Revelation describes “the bride, the Lamb’s wife” as a beautiful city not of the earth, but come down from heaven, “the holy Jerusalem,” having “the glory of God [i.e., having glory equal to God’s]: and her light was like unto a stone most precious” (Rev. 21:10-11).

A similar idea in the Jewish mystical writings of the thirteenth-century Zohar is that the Matronit (Lady or Matron) was part of the godhead in the beginning (the divine tetrad: Father, Mother, Son, and Daughter). She was the daughter and the queen married to her brother, and the son and king (Patai 1967, 126-52). But she went wandering in the earth in search of her lost children. In the Messianic period, she will be restored to her rightful place, in full union with the king, after she has shaken off the dust and ashes of mourning and put on her beautiful garments, representing the authority and power she possessed in the beginning (Isa. 52:1-2; D&C 113).

But the Holy One, blessed be He, will bring back the Matronit to her place as in the beginning. And then what will the rejoicing be? Say, the joy of the King and the joy of the Matronit. The joy of the King over having returned to her and having parted from the Slave-woman [Lilith], as we have said, and the joy of the Matronit over having returned to couple with the King (Patai 1979, 186-87).

In the Midrash, the gathering of Israel during the Messianic period will be led by the Shekhina, the personification of God’s spirit, a female deity of sorts, and the consort of Yahweh:

The day on which the exiles will be ingathered is as great as the day on which the Tora was given to Israel on Mount Sinai. . . . The Shekhina will walk at their head . . . and the nations of the world after them, and the prophets at their sides, and the Ark and the Tora will be with them. And all Israel will be clothed in splendor and wrapped in great honor, and their radiance will shine from one end of the world to the other (Patai 1979, 185).

By separating God’s consort from her errant offspring, these writers redeem the wife of Yahweh from a fallen and, therefore, subordinate role. Thus, her exile is not for her own sins, but a voluntary sojourn as she laments the loss of her children in the manner of Rachel mourning for her children, or the goddess Demeter, mourning the loss of Persephone. In the following passage from the Zohar, the writer quotes Isaiah to the effect that the Matronit’s children are responsible for her exile. And without her, the king is left less than complete and unworthy of glory:

It is written, “Behold, for your iniquities were ye sold, and for your transgressions was your mother put away” (Isa. 50:1). The Holy One, blessed be He, said, “You have brought it about that I and you shall wander in the world. Lo, the Matronit will leave her Hall with you. Lo, the whole Hall, Mine and yours, has been destroyed, for the Hall is not worthy of the King except when He enters it with the Matronit. And the joy of the King is found only in the hour in which He enters the Hall of the Matronit, and her son is found there with her. [Then] all of them rejoice together (Patai 1979, 187).

Isaiah also uses the Jerusalem symbol to depict a mother at one time and at other times her children, which has the effect of elevating the mother figure. In the end time, the mother, Jerusalem, is no longer desolate, but fertile and life-sustaining: “Rejoice ye with Jerusalem, and be glad with her, all ye that love her: rejoice for joy with her, all ye that mourn for her: That ye may suck and be satisfied with the breasts of her consolation; that ye may milk out, and be delighted with the abundance of her glory” (Isa. 66:10-11). This is not a description of an ordinary mother nourishing her children, for Jerusalem’s milk will flow like a river to her children while she dandles them on her knees (Isa. 66:12; Rev. 22:1). This portrayal evokes the image of a fertility goddess who is commonly represented nursing the child or young god at her breast or also represented as a large-breasted or many-breasted figure. (See the illustrations in Neumann’s The Great Mother. Note in particular the Egyptian sky goddess, Nut, who has a stream of milk flowing from her breast to the earth, pp. 32-46 in plate section.) We see a similar depiction of Jerusalem as mother in Isaiah 66:8, where she is described as a woman who “travailed” and “brought forth her children.”

Revelation 12 also records an image of a woman in labor who delivers a “man child.” In his commentary on Revelation, J. Massyngberde Ford notes that the words “woman” or “women” occur so many times, “that the woman symbol is almost as important as the Lamb” (38:188). Moreover, the woman or women portrayed are powerful and pure. For example, the woman in Revelation 12 is described as “a great wonder in heaven,” a mighty woman who is “clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars” (Rev. 12:1). She fights with the great dragon, reminding us of Eve in the garden pitted against the serpent. Being clothed with the sun implies equality with a male sky god, while the moon under her feet connects her with the old Earth Goddess who often bore that symbol. The crown is a symbol of power and kingship (Isa. 62:3—4), while the twelve stars may be connected with the zodiac, which was often for the Jews a symbol of the twelve tribes (Ford 38:197).

Moreover, this imagery connects the bride with still another important set of scriptures. Ford indicates that the text nearest to the portrayal of the woman in Revelation 12 is “the description of the bride in Song of Songs, 6:10” (38:196).

The Song of Songs compares the bride’s beauty to the sun and the moon: “Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear [or bright] as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?” (6:10). The image is of a powerful woman whose majesty surpasses that of a mere mortal. This is one reason some scholars feel that the poem can be traced back “to the ancient myth of the love of a god and a goddess on which the fertility of nature was thought to depend” (May and Metzger 1977, 815). Others feel that the poem simply represents human erotic love (Pope 7c: 192-205). Its sensuous love language has caused a debate since ancient times about the suitability of including the Song of Solomon in the canon. By interpreting it allegorically as the love between God and Israel or Christ and the church, the rabbis and later the Church fathers decided to include it in the canon (Pope 7c: 89-132).

Though this official relation is merely spiritual, we have already seen how the scriptural images of this marriage relationship fit into the pattern of the Mesopotamian sacred marriage, which was both spiritual and erotic. In a detailed analysis and comparison with Sumerian sacred marriage songs, Samuel Noah Kramer shows how the Song of Songs follows the same pattern in terms of its setting, images, language, complex dramatic structure, stock characters, themes, and motifs (1969, 92-102). One example is “the portrayal of the lover as both shepherd and king and of the beloved as both bride and sister” (1969, 92). But for us the most important comparison is the description of the bride. In the Sumerian marriage songs, the bride is Inanna or her human substitute. In the Song of Songs, the bride appears first as a mortal, and yet the description already quoted from Chapter 6 suggests more. Marvin Pope observes:

The combination of beauty and terror which distinguishes the Lady of the Canticle also characterizes the goddess of Love and War throughout the ancient world, from Mesopotamia to Rome, particularly the goddess Inanna or Ishtar of Mesopotamia, Anat of the Western Semites, Athena and Victoria of the Greeks and Romans, Britannia, and most striking of all, Kali of India (7c: 562).

Another remarkable aspect of the Canticle is that the song describes not the love of a dominant male and subordinate female, but their mutuality in love. The structure of the song itself contains long dialogues between the two lovers. Phyllis Trible says that in the Song of Songs there is “no stereotyping of either sex . . . the portrayal of the woman defies the connotations of ‘second sex.’ She works, keeping vineyards and pasturing flocks. . . . She is independent, fully the equal of the man” (1978, 161). Trible sees a connection between the Garden of Eden and the garden in the Song of Songs. Eden is the place of lost glory, but the garden of the Canticle represents a place of redeeming grace, where the errors of Eden are blotted out and man and woman are reconciled to God and each other. Where in Eden, the woman’s “desire became his dominion, .. . in the Song, male power vanishes. His desire becomes her delight. . . . Appropriately, the woman sings the lyrics of this grace: ‘I am my lover’s and for me is his desire'” (1978, 160).

While working on his translation of the Old Testament, Joseph Smith deleted the Song of Songs on the grounds that it was “not inspired writing” (Matthews 1975, 87). I find it ironic that in spite of his rejection, the descrip tion of the bride from this text, which is found nowhere else in the Bible, appears in three of Joseph Smith’s revelations: Doctrine and Covenants 5:14, 105:31, and 109:73. In each instance, the image describes the purified community of Zion or the Church. In Section 109, Joseph prays: “That thy church may come forth out of the wilderness of darkness, and shine forth fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners; And be adorned as a bride for that day when thou shalt unveil the heavens” (D&C 109:73-74).

So who is the bride? Is she a heavenly goddess? Or the earthly community of Israel? Could the bride be a symbol of both? Could there be a real god dess — Eve, Inanna, Ishtar, or Jerusalem — as well as a spiritual community of the faithful — Israel, the Church, or the covenant people of the Lord? And are the faithful on earth to await, like the ten virgins, not only the coming of the bridegroom, but the unveiling of the heavenly bride from above? Is there to be a sacred marriage between her and Jesus Christ? And when is this wedding to occur?

Apostle Orson Pratt wrote in The Seer: “There will be a marriage of the Son of God at the time of His second coming” (1854, 170). Of course, the purpose of Pratt’s discourse was to show the reasonability and importance of plural marriage, for he stated that Christ would have many wives: the queen described by John the Revelator as the “Bride of the Lamb,” and others, including the five wise virgins who would marry him at the “marriage feast of the Lamb.”

Is the final sacramental feast of Doctrine and Covenants 27 a wedding supper? How does this relate to the statement of Joseph Smith that at Adam-ondi-ahman Adam would turn the keys over to Christ? (Ehat 1980, 9) Who are the virgins who will enter the bridal chamber? What do these symbols mean in terms of Christian and Mormon eschatology?

These are questions that will probably not be answered either through historical analysis or even by the efforts of speculative theologians.

However, as we contemplate and analyze the symbols and rituals of our own tradition and compare them with those of others, we may conclude at least that there is embedded in Mormonism, as in Christianity and Judaism, some hidden traces of a goddess. If she were allowed to emerge from obscurity and if there developed around her a body of teachings that could be harmonized with our existing beliefs, they would result in a theology that could, perhaps, provide the basis for a reevaluation of the Godhead in terms of the sacred marriage of the Heavenly Father and the Heavenly Mother and of the Son and the Daughter. Such a view, based upon a christological hieros gamos — sacred marriage -— could serve as the foundation for a fuller and more completely integrated spiritual experience for many people in the Church. Such a view might be less rigid, less narrow, more likely to encourage personal individuation, more likely to allow men and women to mature, with greater facility, beyond the limits and tensions of mere matriarchy or mere patriarchy.

And though the emergence of such a theology does not appear imminent, the rumor of it cannot be denied.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue