Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

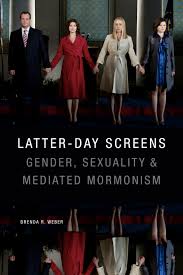

Latter-Day Screens: Mormonism in Popular Culture Brenda R. Weber. Latter-Day Screens: Gender, Sexuality & Mediated Mormonism

Latter-day Screens is a fascinating, compelling, and, at times, frustrating look at a wide range of Mormon-related media. This is largely due to the central conceit of the book—essentially working with Mormonism as a meme and analytic—which works brilliantly in some instances but feels limiting and artificially constrains the discussion in harmful, rather than productive, ways in others. Weber’s background and expertise in gender and media studies shows throughout the book. She argues that “the amalgamation of materials that turns on Mormonism as a trope—and public conversation about those texts—has had the effect of opening more channels for progressivism, by which I mean a pluralized, diverse, and polylogic regard toward meaning and identity” (19). Weber provides some compelling analysis in support of this audacious claim, though perhaps a deeper engagement on a narrower plane would have been more persuasive.

Weber notes in the introduction that by “the word ‘Mormonism’ I mean not specific or actual F/LDS people, practices, or histories as much as the multiple stories told and retold about these things. It is thus mediated Mormonism as both an idea (meme) and a way of thinking (analytic) that beats at the heart of my inquiry” (15). The limitation of such an approach is that the people, practices, and histories of Mormonism (or Mormonisms, if you prefer) are often an inevitable and inextricable piece of the mediated versions she discusses. Weber doesn’t completely ignore people, practices, or histories, and in fact seems quite eager to share snippets that further her broader ideological argument and match her own lived experience, which may or may not resonate with Mormons of a variety of stripes.

The book’s engagement with Mormonism as a practice, history, and religion was often frustrating—occasionally including slight factual errors like men gaining the status of elder at age twelve (p. 50) and other disputable information. However, I grew much more sympathetic in retrospect when I read the epilogue, which describes Weber’s own fraught relationship with Mormonism growing up Presbyterian in Mesa, Arizona. The Mormonism that Weber describes here, and in places throughout the book, felt foreign or like a distortion of my own lived experience with Mormonism. Yet, reading Weber’s own firsthand account at the end of the book caused me to reflect more graciously on what had come before.

Weber’s broad consideration of what Mormonism is functions as one of the greatest strengths of the text. She engages with all sorts of portrayals of a large swath of Mormonisms, including a wide range of fundamentalist and polygamist groups. The book is undoubtedly richer for this choice and the considerations that it brings about, even if it will likely cause some frustration to historians and scholars of religion who would appreciate a clearer discussion of the various historical and theological backgrounds of the groups present in Weber’s media selections. Such context could have enriched her conversations and analysis.

Weber engages throughout the book with various aspects of Mormonism, largely clustered around gender and sexuality, though chapters cover spiritual neoliberalism (a phrase Weber defines as “a neoliberal regard toward self and systems emphasizing smart choices, care of the self, maximum efficiency, and reduced government intervention” that “mandates loftier, more spiritual goals as markers of achievement—personal well-being, enlightenment, heavenly happiness, the godhead” [54]), racial implications of the “Mormon glow,” polygamy, feminism, and queer desire.

The text is best when Weber is engaging closely with one of the various media texts that she has selected for analysis. Weber is undeniably skilled at analyzing these texts (often doing a close reading) and remarkably adept at pointing to complexities, contradictions, and paradoxes that are embedded within each of the moments that she has chosen to highlight. Perhaps the moment that best illustrates this skill is when Weber explores the portrayals of Warren Jeffs and other predatory polygamists in chapter 4. Weber argues that “polygamy fosters feminism” because in these mediated depictions “of male excess, these stories often function as self-making devices for women” (169). She continues by writing that “it is not the ego-driven cardboard cutout leader but those traumatized by his autocratic power that have stories to tell and interiorities to share” (169). This analysis is born out through a careful reading of two reality TV shows, Escaping Polygamy and Escaping the Prophet, and the rhetoric surrounding FLDS polygamist Warren Jeffs. The chapter ends with a discussion of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, both of whom she presents in ways that some will find off-putting, if not misleading, or at least incomplete.

Weber engages almost exclusively with media about but not produced by Mormons (with a few minor Mormon-produced exceptions) including Sister Wives (reality TV), Big Love, The Book of Mormon (musical), interviews with the Osmonds, various news and other media featuring and about Elizabeth Smart, MLMs, various podcast episodes hosted by John Dehlin, a smattering of memoirs by former Mormons, Marriott hotels, Teenage Newlyweds, countless think pieces from online news magazines during the “Mormon Moment,” the novel The Lonely Polygamist, the Bundys, and even the Bloggernacle. Weber chose texts that are primarily in the popular culture surrounding Mormons but coming from outside Mormonism, most of which are relevant to her thesis about the progressive nature of the gender and sexuality conversation surrounding mediated Mormonism. Weber doesn’t offer an explicit reason for almost completely ignoring Mormon-created media, though I’d assume the reason is tied to her focus on Mormonism as meme and that Mormon-created media would be too close to Mormonism as a people, religion, history, etc. Further work could take the analyses that Weber performs here and look at what happens to the thesis when the focus is on Mormon-created texts (films like Jane and Emma, Brigham City, and the Halestorm Entertainment comedies; novels like The Scholar of Moab or the Linda Wallheim mysteries; and plays like Pilot Program or Huebener).

Latter-day Screens has a lot on its mind and seems to barely scratch the surface of the potential for the ideas and themes that Weber is exploring. Each chapter felt like it could have been its own monograph, exploring more deeply each facet of the context that surrounds and informs the various texts. The book is provocative in some of the most positive ways by laying the groundwork for all sorts of future scholarship that could play with Mormonism as a meme and analytic. One such idea that was teased, which I would love to see more work on, was “Joseph Smith, founding prophet and fallen martyr, as a camp celebrity figure” (194). This brief section is the moment from Weber’s text that lodges itself most firmly in my mind and speaks to the thought-provoking nuggets of insight that are scattered throughout the text.

Weber’s text is a fascinating exploration of a wide range of Mormonisms and how they are mediated through all sorts of media, essentially working with Mormonism as it is replicated throughout the broader popular culture and not overly, or at all, concerned with how it exists as a practice, people, or history. This move leads to some deeply insightful analyses and also some blind spots.

Brenda R. Weber. Latter-day Screens: Gender, Sexuality, and Mediated Mormonism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2019. 384 pp. Paper: $29.95. ISBN: 978-1-4780-0486-8.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue