Articles/Essays – Volume 15, No. 4

An Introduction to Mormon Administrative History

Institutional vitality has characterized The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints from its organization with six members in 1830 to over five million by 1982. Its capacity to govern and manage an ever-enlarging membership has helped assure its survival yet its administrative structure, flexible enough to pro vide for growth and tight enough to ensure control, has received little attention. The essays that follow should help meet this need.

Before April 1830, Joseph Smith, with help from Oliver Cowdery, had out lined key doctrines and church organization, a document now known as Doc trine and Covenants, section 20. Having earlier received the necessary priest hood authority from heavenly messengers, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery officially organized the church according to laws of the state of New York on 6 April 1830.

The first months’ government for the infant organization was informal. Joseph Smith was recognized as the prophet and leader; Oliver Cowdery was his assistant and spokesman. The first years of Mormon history are the story of the growth from this informal government to an “oligarchy of leading elders.” By 1835 the basic contours of the Church’s administrative structure—the presiding quorums—were in place.

The Church began with five priesthood offices in 1830: apostle, elder, priest, teacher, deacon. The offices of bishop and high priest were added in 1831. But all of these early positions were local, held by lay members with no presiding authority. By 1831 Joseph Smith’s ecclesiastical position had been more clearly defined, but it was not until January 1832 that he was formally sustained by a conference vote as president of the high priesthood. Two weeks later he officially chose and ordained Jesse Gause and Sidney Rigdon as counselors. With these 8 March 1832 calls the Mormon hierarchy officially began. Early revelations and instructions from Joseph Smith established this First Presidency as the supreme authority on all matters relating to the Church.

The next major development was the organization of a Quorum of Twelve Apostles on 14 February 1835. While men had been earlier ordained as apos tles, this act established a special unit of church government. Although their responsibilities were limited during the next six years, in time this Quorum stood next to the First Presidency, and its senior member has become, upon the death of every president beginning with Joseph Smith, the new leader of the Church.

The third presiding quorum in the Mormon hierarchy, the Seventies, was organized in 1835, two weeks after the organization of apostles into a Quorum, when Joseph Smith began ordaining men to the office of Seventy. Their task was missionary work. They were organized into quorums of seventy men, with the First Quorum as the presiding quorum and its first seven members as presidents of all the seventies in the Church. From the beginning, they were to receive instructions and directions from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, but were to “form a quorum equal in authority” to them (D&C 107:25-26). During the nineteenth century, most of the Church’s proselyting missionaries were seventies, yet with the exception of the Patriarch, the office of the Seventy in Church history is least understood.

The fourth presiding unit in the LDS hierarchy is the Presiding Bishopric. Edward Partridge, called on 4 February 1831, was the first bishop in the Church. He was joined in December 1831 by Newel K. Whitney. Only gradually did their responsibilities become known either to themselves or to the Church. Very early they were assigned to “watch over the Church” and to take an interest in the poor with the special assignment of administering donations received for the needy. By 1835, Joseph Smith had revealed that the bishops should also be judges in the Church and were to be responsible to the First Presidency. They were to preside over the lesser priesthood offices of deacon, teacher, and priest, and were to be increasingly concerned with the “temporal” or economic affairs of the Church (D&C 107: 15-17, 68-76, 88; Joseph Smith later added vs. 76-93 to this section). By 1839, two more bishops were called, but each had geographical responsibility (Missouri and Ohio) for a loose group of members. Presiding authority remained undefined.

It was during the Nauvoo period (1839-46) that, originally for voting purposes, wards were first organized. In time these political subdivisions became useful ecclesiastical units over which a bishop took responsibility. The office of Presiding Bishop was first designated in 1840, but no Presiding Bishop functioned until about 1847. Dale Beecher’s essay in this issue provides a convenient summary of his lengthier studies on the history and functions of the office of bishop.

The crisis that occurred at the death of Joseph Smith is in large measure explained by the evolutionary nature of church government before 1844. Joseph Smith had thought of at least eight different ways or modes of succession. While recent study suggests that the most immediately viable leadership mode was the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, their position was not publicly obvious. This administrative uncertainty helps explain the growth of schismatic groups after 1844.

From the Church’s beginning, its leaders have interpreted their missions as both spiritual and temporal. Thus, administrative studies must consider such religious elements as priesthood quorums, the Relief Society, and the various auxiliary programs (Sunday School, Mutual, and the Primary) which are primarily spiritual in their purposes, as well as the more temporal dimensions of LDS administration. Though subsumed in the goals and purposes of Mor monism’s religious functions, they must be seen as part of the larger bureaucracy. For example, the Trustee-in-trust and Corporation of the President have immense power within Mormonism as well as in the larger culture. Very often, management problems and attitudes which surface in temporal business affairs of the Church affect its more spiritual matters. Jessie Embry’s examination of the Relief Society’s grain storage program documents precisely such an administrative situation.

Furthermore, administrative history can tell us not only how the individual relates to the corporate system but also how our history as a people is manifest in the organizational structure. Once the student realizes that corporate Mor monism was only outlined by 1844, much of Mormon history since Joseph Smith’s death takes on a fuller meaning. The changes of administrative structure document efforts of Latter-day Saints to become the Saints they were commanded to be. In the organizational charts the theology of Mormonism is put into action; here the goals of the gospel are given institutional embodiment. In a fundamental way, the essence of Mormonism is found less in the scriptures or conference reports than in manuals and guides. The flowcharts reveal the framework of an institution whose lifeblood circulates through meetings, committees, quorums, classes, and councils.

This condition in itself is a marked change from the pragmatic and generally informal nineteenth-century Church. The key to Mormon solidarity during those years was not bureaucratic structure even though the quorum structures came west. Rather, sealings and adoptions cemented authority and loyalty within the Church.

With stability came a more formal administrative structure. Because eco nomic prosperity was vital, the organizational devices for managing economic programs were often incorporated into the ecclesiastical structure. Leonard Arrington has identified six such devices: the office of Trustee-in-trust; the department of public works; the tithing office (later the Presiding Bishop’s Office); the Perpetual Emigration Fund; the Relief Society; and the office of Brigham Young, who, as both president of the Church and as a private entrepreneur, sought to apply correct spiritual principles to all areas of life. Each of these institutions needs further study.

When Brigham Young died in 1877, Church membership numbered about 150,000, newly organized into 20 stakes and 240 wards. Change did not stop with Brigham Young. Less visible changes were occurring on the highest levels at the turn of the century as Church leaders came to terms with Utah state hood while seeking greater unity among themselves. Thomas Alexander’s essay in this issue details and analyzes these unpublicized but momentous shifts of policy and administrative style.

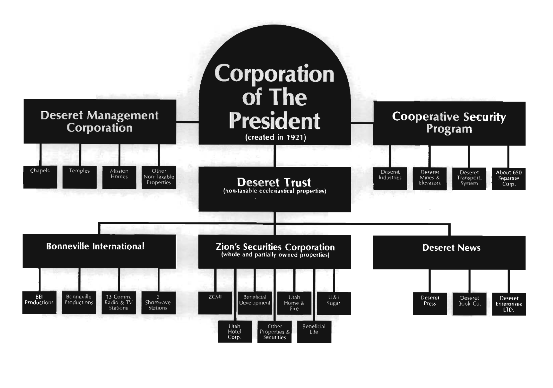

In large measure, most of the administrative changes in the Church in the twentieth century have been modifications of programs already established; thus many of the changes were not so much to the Church as an ecclesiastical structure as to the Church as a corporate entity. For example, some of the more important include acquiring the Deseret News in 1900; purchasing historic sites beginning in 1903 and the gradual establishment of Bureaus of In formation; the Second Manifesto (1904); opening the LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City (1905); the first seminary class (1912); regular Family Home Evenings encouraged by the First Presidency (1915) ; creation of the Corporation of the President (1921); Zion’s Security Corporation (1922) ; Priesthood Auxiliary movement (1928) ; the Church Security Program or Welfare Plan (1936); assistants to the Twelve first called in 1941; the Indian Placement Program in 1947, the same year Church membership passed one million; Priesthood Correlation Program (1961); Regional Representatives (1967); the unification of Church Social Services programs (1969) ; the first training course for bishops (1970) ; consolidation of Church magazines (1971) ; new Church Office Building opened (1972); fifteen Church Hospitals turned over to Intermountain Health Care, Inc. (1972) ; reorganization of the Historical Department of the Church (1972); expansion of the First Quorum of the Seventy (1976) ; and the Official Declaration of the First Presidency extending the priesthood to all worthy males of the Church in 1978. In addition, many changes have come to corporate Mormonism. Table 1 provides a simplified view of the corporate structure of the Church. These dimensions of Church administration have received very little serious attention so far.

Three essays in this issue address contemporary topics relating to Church administration. Garth Jones takes an international perspective of Church administration, using Indonesia as a case study. He raises serious questions about the future of the Church in Third World nations—questions especially centered in the manner the gospel is presented for non-Western cultures.

Brooke and Jill Derr probe how power is manifested and influence felt outside the formal, hierarchal structure of the Church. Their essay is particularly important for its examination of the informal power women have exercised in Mormon history and the contribution this analysis makes to women’s studies.

Dennis Lythgoe, in a carefully documented personal essay, records his frustrations caused by one of the largest departments in the Church bureaucracy— the Building Committee —while Frances Whitney Richardson describes some of the social implications of Church change and Richard Cummings identifies literal mindedness as both a strength and a weakness of Mormon group life.

Needless to say, these essays do not approach a complete examination of Church administration. There are literally hundreds of untouched topics. Thanks to the work of Michael Quinn and William Hartley, a foundation for the study of the Church’s priesthood quorums has been laid. Conspicuous gaps are histories of the office of Patriarch, the history of the seventies, the Presiding Bishop’s office, most of the general Church committees including the Finance Committee, those dealing with education, building, missionary work, genealogy, finances, welfare, and the Lamanites. Almost nothing has been done on the Church judicial system, the growth of such powerful but essentially anonymous bodies as the Correlation Committee, the Public Relations Department, the separately owned corporations, and the Curriculum Department which prepares the official manuals. In addition to the history and functioning of these groups on the general level, the question still remains unanswered of how the Church operates at the ward and stake levels at different times and in different regions. Much academic work on organizational theory and behavior would provide valuable insights into Church organization when scholars prepared to make the connections turn to this fruitful field.

Ideally, an organization should be an instrument of community and communion; all too often organization hampers such experiences. Yet such experiences, paradoxically, cannot take place without an organization as the Lord has outlined his will for his Church. These essays are offered in the hope that a proper balance can be found between administrative efficiencies and personal and eternal relationships.

Notes on Further Readings

For a comprehensive guide to the literature on this topic as well as suggestions for further research, see David J. Whittaker, “Mormon Administrative History: A Source Essay,” in Leonard J. Arrington and William G. Hartley, eds., For the Perfecting of the Saints: Essays in the History of LDS Organization and Administration (forthcoming).

Valuable sources on early organization are Larry C. Porter, “A Study of the Origin of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the States of New York and Pennsylvania, 1816-1831” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1971), pp. 154-276; Porter, “Dating the Restoration of the Melchizedek Priesthood,” Ensign 9 (June 1979) : 5-10; Mario DePillis, “The Quest for Religious Authority and the Rise of Mormonism,” DIALOGUE, A JOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT 1 (Spring 1966): 68-88; Richard L. Anderson, “Who Were the Six Who Organized the Church on 5 April 1830?” Ensign 10 (June 1980) : 44, 45; D. Michael Quinn, “The Evolution of the Presiding Quorums of the LDS Church,” Journal of Mormon History 1 (1974) : 21-38; Wesley P. Lloyd, “The Rise and Development of Lay Leadership in the Latter-day Saint Movement” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1937) ; Jay R. Lowe, “A Study of the General Conferences of the Church . . . , 1830-1901” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1972) ; T. Edgar Lyon, “Nauvoo and the Council of the Twelve,” in F. Mark McKiernan, et al., eds., The Restoration Movement: Essays in Mormon History (Lawrence, Kan.: Coronado Press, 1973), pp. 167-205; Ronald K. Esplin, “The Emergence of Brigham Young and the Twelve to Mormon Leadership, 1830-1841” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1981); Reed C. Durham, Jr., and Steven H. Heath, Succession in the Church (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1970) ; William G. Hartley, “Ordained and Acting Teachers in the Lesser Priesthood, 1851-1883,” BYU Studies 16 (Spring 1976): 375-98; and Donald Gene Pace, “The LDS Presiding Bishopric, 1851-1888: An Administrative Study” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1978).

James N. Baumgarten, has written “The Role and Function of the Seventies in L.D.S. Church History” (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1960), a useful overview, while William G. Hartley’s important study on the crucial 1880s period for the Seventies will be forthcoming in DIALOGUE, 1983. Papers on the office of the patriarch during William Smith’s tenure by E. Gary Smith and Irene M. Bates, presented during the 1982 Mormon History Association annual meeting, will be forthcoming in DIALOGUE, 1983, as will Richard L. Jensen’s look at Relief Society activity during the 1847-67 period, two decades originally considered barren.

Events after Joseph Smith’s sudden death are chronicled in D. Michael Quinn, “The Mormon Succession Crisis of 1844,” BYU Studies 16 (Winter 1976) : 187-233; Ronald K. Esplin, “Joseph, Brigham and the Twelve: A Succession of Continuity,” BYU Studies 21 (Summer 1981): 304-41; and Quinn, “Joseph Smith Ill’s Blessing and the Mormons of Utah,” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 1 (1981): 12-27; also DIALOGUE, 15 (Summer 1982): 69-90.

Indispensable studies on the social role of sealings and adoptions are Danel Bachman, “Plural Marriage among the Mormons before the Death of Joseph Smith” (M.A. thesis, Purdue University, 1975); Gordon Irving, “The Law of Adoption: One Phase of the Development of the Mormon Concept of Salvation, 1830-1900,” BYU Studies 14 (Spring 1974): 473-88; D. Michael Quinn, “The Mormon Hierarchy, 1832-1932: An American Elite” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1976) ; and Lawrence Foster, Religion and Sexuality (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981). Leonard J. Arrington describes economic devices of socialization in “The Six Pillars of Utah’s Pioneer Economy,” Encyclia: The Journal of the Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters 54, pt. 1 (1977 ) : 9-24 .

Information on twentieth-century administrative changes and adjustments can be found in Richard O. Cowan and Wilson K. Anderson, The Living Church (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1974) ; Richard O. Cowan, The Kingdom Is Rolling Forth: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Twentieth Century (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1971); Cowan, “The Priesthood-Auxiliary Movement, 1928-1938,” BYU Studies 19 (Fall 1978) : 106-20; Thomas G. Alexander, “Between Revivalism and the Social Gospel: The Social Advisory Committee, 1916-1922,” BYU Studies 22 (Fall 1982) ; and Armand L. Mauss, “The Fading of the Pharaoh’s Curse: The Decline and Fall of the Priesthood Ban Against Blacks in the Mormon Church,” DIALOGUE 14 (Autumn 1981): 10-43. Examinations of contemporary organizational issues include Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1980), ch. 14; Bill Beechan and David Briscoe, “Mormon Money and How It’s Made,” Utah Holiday (22 March 1976): 4-11; “Change Comes to Zion’s Empire,” Business Week (23 November 1957) : 108-16; Jeffrey Kaye, “An Invisible Empire: Mormon Money in California,” New West (8 May 1978): 36-41; Randall Hatch, “The Mormon Church: Managing the Lord’s Work,” MBA (June 1977) : 33-37; Fred C. Esplin, “The Saints Go Marching On: Learning to Live with Success,” Utah Holiday, June 1982, pp. 33-48; and J. Bonner Ritchie, “The Institutional Church and the Individual: How Strait the Gate, How Narrow the Way?” Sunstone 6 (May-June 1981) : 28-35.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue