Articles/Essays – Volume 52, No. 3

A Mormon Boy Meets a King

“Stop gawking at that guy,” Mother said, as I stood staring at a man while shopping in a five and dime store in Idaho Falls. I had never seen a black person before. I stood fascinated in my mom-made bib overalls, until Mom lifted her eyes from the school supplies to her six-year-old son—who had stood too still, for too long, for her not to notice.

A few years later, my dad related a story to me. At Simplot’s dehydrating plant, Dad tended two boilers to steam the water from potatoes for soldiers during World War II. An African American began working on the potato production line, and in a few weeks, Dad looked out his window and saw a policeman by his motorcycle talking to the black man on the sidewalk. Days later the black man stopped coming to work. The policeman had asked him politely to leave town as soon as convenient. Decades later I learned that the town fathers had the police do this to discourage blacks from settling in Blackfoot.

On Saturday nights in 1950, Blackfoot teens gathered inside and outside of Roy’s Ice Cream parlor. Once, two black men came walking west along Bridge Street, heading out of town. Eric Sims spotted them first, ran after them, and ten kids followed. The black men began singing and put a shuffle in their steps. We kids did likewise, singing and shuffling along together down the middle of the street. When we tired of this venture, we turned around and skipped back to the ice cream parlor and the blacks walked on west out of town.

In 2019, I wonder how these black men felt. Did fear force them to sing and shuffle while walking briskly out of Blackfoot away from 5,800 whites in 1950?

Going south, only the Blackfoot River separated Blackfoot from the Shoshone-Bannock Reservation, and many Indian kids attended Blackfoot schools. Families like mine bought wagonloads of hay from Indians as well as deerskin moccasins and gloves. Stores also sold their products. In the lower grades at Irving Elementary, some of us played cowboys and Indians during recess and lunchtime. I recall being a cowboy and fighting real Indians led by Emery Chico Tendoy, who was a year or so older than I. We were all friends, never hurt one another in our war games.

The sleazy bars along Main Street, one owned by a Hansen relative, a family secret, had signs on the door, “No Indians or Dogs Allowed.” Discussing this as students at Idaho State College, my friend Bill Christenson and I laughed as he said, “What dog would enter those bars anyway?”

Upscale bars, such as Snowballs and the Silver Spur, had no such signs. During the annual layoff at the cheese factory one winter, my dad tended bar at Snowballs and told our family about men crowding around a billiard table to watch Henry Blackhawk aim his cue stick at the cue ball. Blackhawk was Blackfoot’s champion snooker player. In high school we elected Wyman Babby to be president of my senior class, and after high school three females in my class married Indians. I believe all of these Native Americans, regardless of their tribe, lived on the Shoshone-Bannock Reservation.

I graduated from Blackfoot High in 1953, worked the summer spik ing rails to ties for the Union Pacific Railroad, and became a blacksmith apprentice in the fall. I worked with a Pentecostal preacher, who invited me to visit his chapel one Saturday afternoon, who read me Bible verses, and who mentioned a concept new to me: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints did not ordain negroes. Next day at church, I talked with returned missionary Doyle Elison. We discussed ordination, and at age eighteen I learned we did not ordain blacks. I do not recall the scripture he read to me to support this policy.

After serving an LDS mission in Canada and receiving an AA from Ricks College, I attended Idaho State College and joined the debate squad in 1960. My partner Paul Defosses and I entered the prepared speech contest during a debate meet at Utah State College. While awaiting our turn, we watched a girl from Westminster College give a speech in which she compared blacks to silkworm pupae and the LDS Church to silk producers, who boil the silkworm cocoons to kill the pupae, who unravel each cocoon into a single silk thread hundreds of feet long, and who process the thread into silk.

In an hour Paul and I finished our speeches and saw the silk lady walking out of the building. Paul ran to catch her and I followed. He said to her, “You’re just the lady we’ve been looking for.” He praised her speech and invited her to a party he invented, saying we needed a date for an invented black male on our debate team. The invitation to date a black student stunned her, and she stammered she could not. Did she deliver her silkworm oration again?

Upon my graduation from Idaho State in the spring of 1961, my wife Carol and I moved to Virginia and began seeing blacks daily. In the fall, I was working at Potomac Electric Power Company. Returning from coffee break one morning, I was in a deep discussion with coworker Stan on an elevator with a black operator. “Nigger” slipped from my lips and conversations ceased. The riders covered themselves in a silence unknown since before the Big Bang. Moments passed, the elevator stopped, and Stan stepped out, holding his hand over his mouth to curb laughter. I was walking behind him, red-faced, hoping to self-evaporate.

I noticed my changing sensitivity to race when Blackfooter Delwin Daniels visited us in the summer of 1962. He arrived in DC with a delegation from Blackfoot’s Chamber of Commerce and visited the office of Congressman Ralph Harding, where Carol worked. A schoolmate through grade eleven, Delwin had become the jovial, 300-pound owner of a small grocery store. As we dined out that evening, I recall my dismay on hearing him say, “There’s sure a lot of niggers out here,” but I knew his Blackfoot idiom did not intend meanness. I related to him the moment when this word had departed from my mouth on an elevator with a black operator.

In 1962, a few months into my first career job, a contract negotiator for the Navy, Glen Roane joined my group of ten negotiators. We purchased underwater ordnance, such as nuclear torpedoes for the Polaris submarine, and related research, such as sonar to discern between ships and large fish. Our manager assigned Glen a desk next to mine. We shook hands and I began associating with the only black person in our office and learning his life stories. Glen became my window into his world. I learned he had received his law degree in 1957 and had taught high school and carpentered until 1961, when pressure from the civil rights movement enabled him to secure a professional job. In the 1990s, I interviewed Glen and learned the following details of his life.

Glen Roane was born July 26, 1930, the seventh of ten children. With five brothers and four sisters, he had grown up on a 58-acre farm in Westmoreland County, Virginia. The family raised tomatoes, corn, and wheat for cash and all types of vegetables for the table. A mill ground their wheat, four or five bushels at a time, and his mother, who had a fourth grade education, made biscuits every morning for her ten children.

Glen’s father, who had finished the seventh grade, worked on and off the farm, had built the family’s house, had constructed other houses in the area, and had taught his sons carpentry. Glen used these skills to earn money for college and to support his family for a few years after his marriage.

In Glen’s experience I see my own. My mom and dad finished the eighth grade, and we lived on seven acres where we produced most of what we ate: milk and meat from our cattle and pigs, fruit from our apple trees, and vegetables from our garden. Mom canned fruit, meat, and vegetables for our winter meals and baked our bread. During my childhood, cash came from my dad’s jobs: Kraft Cheese, Union Pacific, Simplot Potatoes, and for a year or so he owned a truck and hauled milk from farmers to the cheese factory.

On the side, Dad bought and operated a sixty-acre farm with my grandfather during World War II. He sold it after a year, bought a forty acre farm, raised a crop or two, sold it, and then increased the number of hogs and cows raised on our seven-acre lot located one block from the city limits. Then Blackfoot passed an ordinance against raising pigs within the city limits.

I could not understand. Why not ban cows too? Did the influence of our neighbor, who had a large pine-post corral and shipped cattle between California and Idaho, affect the decision to exclude pigs, but keep cows? If my dad had fought for his rights, would pigs still have been allowed? The only animals we raised during my last years at home were milk cows and a steer a year for meat.

A couple of Glen Roane’s aunts and his step grandmother taught school, and they encouraged him to get an education. Glen memorized their most quoted phrase: “If you’re going to make a living in this world, you’ve got to have an education.” After leaving A. T. Johnson High School in 1946, Glen entered Virginia State University, a school for blacks, where in 1952 he became a Distinguished Military Graduate with a degree in agronomy and a commission as a second lieutenant. Then Glen entered the Army for two years.

I grew up among people with manual jobs; I had limited exposure to professions. Uncle Calvin, the only degreed person in our family, taught physics at Blackfoot High School and had to work a second job to meet his bills. Other teachers did the same, so I had no incentive to become a teacher. Doctors, dentists, and lawyers lived on the east side of the tracks, the side with paved streets, indoor toilets, and toilet paper instead of pages from the Sears Roebuck catalog. I grew up seeing myself incapable of pursuing their educations and professions.

In high school I had little interest in knowledge and had a 1.5 GPA my senior year. My first bout with college came when the railroad changed from steam to diesel engines and some blacksmiths lost their jobs, as did I—the last apprentice hired. I attended Idaho State winter semester of 1954 and dropped out. As I prepared to enter the Army in December of 1954, my bishop, Clarence Cox, encouraged me to serve an LDS mission. I believe the divine entered the process that led me to sell my ’50 Ford convertible with a Lincoln engine and begin a two-year mission in Canada in March of 1955.

On my mission, what I learned, I taught, and knowledge took on value. Barnard Silver—my second missionary companion, who had completed two years at MIT—said I could memorize scriptures and poetry as fast as he, that I had a high IQ. He urged me strongly to return to college after my mission. A year later the mission president called me to serve as district president of Calgary, an oil-rich area with many educated Mormons, including the mayor.

Soon, I found myself having lunch on Sundays with Apostle Benson’s daughter, Barbara, and her husband, Dr. Robert Walker, who became a nationally known cardiovascular specialist. My calling also gave me the opportunity to meet often with a lawyer, a stockbroker, and a petroleum engineer. Nine months in this context left me comfortable associating with educated people and a desire to attend college.

It seems a paradox that growing up in a black environment gave Glen Roane access to a larger view of reality than white Blackfoot gave me. His experience also seems superior to mine in preparing a person to value education and to survive the move from high school to college.

After Glen’s army service, he attended the Howard University School of Law on the GI Bill and received his JD degree in 1957. Glen said this happened next:

I graduated and went to Baltimore to take the Civil Service exam for claims examiner. I passed it with an 88, got five points veteran’s preference, which gave me 93. They interviewed us en masse and there were seven or eight people, maybe ten, two blacks in the group. They asked me one question, “Do you think you would like this job?”

I had already gone there for two interviews. I had taken the exam and then came back for another interview. Of course I would like the job. That’s the only thing they asked. But they did not give me a job. When I went back to see why I did not get a job, they said, “Yes, you passed and got 93 with the veteran’s preference, but we did not think you could make a satisfactory adjustment to the duties of a claims authorizer.”

What adjustment are you supposed to make? Those were the days before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Glen also applied for jobs at the Library of Congress and the Justice Department with the same result, no job. And he took bar exams. “I tried to pass the Virginia Bar . . . and hit the Virginia Bar at the top of massive resistance,” Glen said. “They would let one black pass the Virginia bar—two pass, zero pass, one pass, two pass, zero pass. They did that for about six years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.” This Supreme Court decision made separate schools for blacks and whites unconstitutional. All justices supported this decision, voted nine to zero—and in Virginia, blacks suffered consequences. Of these consequences Glen said,

Until 1954, 50 to 65 percent of Howard graduates passed the Virginia Bar, just like the whites, same percentage almost. In 1955 and after, the Blacks who took the bar exam ended up taking it again. We were just piled up on top of each other. They were examining more blacks than whites because we were taking it over and over again.

So I never did pass the Virginia Bar. I took it three times and quit. I failed the DC Bar right out of school in ’57, but I had prepared for the Virginia Bar. I did not prepare for the DC Bar; I just sat for it. In 1960, I took the DC Bar again, passed it, and was admitted to the bar in 1961.

While pursuing a law-related job, Glen also had to find ways to feed his family. In 1957 he taught chemistry and general science at Pomonkey High School in Charles County, Maryland. The next year he taught the same subjects at A. P. Johnson High School in Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1959 he began teaching at Northumberland High School, but quit after fall semester to earn more money at a carpentry job in Washington, DC. Glen was earning only $3,500 a year teaching school.

I asked how he got his job with Veterans Affairs before transferring to the Navy Department. Glen said, “Well, in 1961, I visited the VA, something connected with my insurance, and I saw these jobs for adjudicators. I am dressed casual, like a carpenter, reading the duties of an adjudicator. This guy sees me and comes over, tries to steer me to the list of manual jobs. I tell him the adjudicator job looks more interesting, and I look at him and he says, ‘You don’t have a law degree, do you?’ I say yes and he fumbles for an application and asks me to complete it.”

Since Glen had filled out applications before without receiving results, he said in frustration, “I am not filling out any more applications. You do not intend to hire me simply because I am black. I have filled them out before, got my hopes up, and got nothing.” The two talked on, both embarrassed because of people gathering to listen to them. Finally, Glen agreed to fill out the forms and take the examination again. He passed another exam, but this time he got a job!

One night, Glen and I met one of our contractors at the stadium in DC to watch the Senators play baseball. The game ended and Glen invited me to stop by his house in DC on my way home to Greenbelt in Maryland. Before entering his house, he walked me around the block under the streetlights, showing me the manicured yards of his neighbors. He said, “Now, why can’t we live in your suburbs?” I shrugged. Inside his home, he tossed his baby into my arms, and maybe I appeared to cuddle the child in stride, but inside I felt a happening. I had not touched a black baby before. Holding the child kindled feelings I cannot describe and may not have mentioned before. Prejudice—or just a new experience?

I became president of the elders quorum of the College Park Ward in Maryland and began a series of Sunday firesides presented by known Mormons such as J. Willard Marriott and Senator Wallace Bennett, as well as their wives, and lesser-knowns such as June Thane and Dwayne Stephenson. No one objected until I invited Stephenson.

Lynn, a law student, complained to the stake couple in charge of firesides, Robert and Della Stilmar, saying Dwayne had communist ideas, implying he was a sympathizer with our archenemy at the time, the Soviet Union. The fireside couple, a lawyer and his wife, discussed the situation with me; I did not know Dwayne but he seemed okay. I urged them to attend the fireside so they could discuss it with knowledge if Lynn made it an issue.

Dwayne told his story about the newly formed Peace Corps. He had learned French on his mission, had graduated from BYU, and had become active in politics as a Kennedy Democrat. After Kennedy established the Peace Corps, Dwayne applied for the position of director in a French-speaking country in Africa. The hiring process included a series of interviews. One interviewer noted Dwayne was a Mormon.

This interviewer said she had met only one other Mormon in her life, said she had met him at a leadership conference for college students. In a bull session at the conference one evening, the topic turned to blacks, whom some believed inferior to whites (at the time, some states used this notion to justify separate schools for each race). The Mormon student body officer from BYU said he did not think blacks were inferior; he knew they were inferior, and for that reason his church did not give them the priesthood.

This statement had upset Dwayne’s interviewer; she recalled not only the statement but also the religion and school of the author. Dwayne told the interviewer not to judge all Mormons by one student. Dwayne said he believed blacks were equal to whites and he would change the priesthood policy if he could. Dwayne left this interviewer with little hope of being hired.

The interview process ended and Sargent Shriver, the first Peace Corps director, invited Dwayne to his office. Shriver said Dwayne had impressive French and the best credentials for the position—but it was too risky to hire a Mormon for this high-profile director job. Upon arriving in the African country, a reporter with Marxist leanings would surely interview Dwayne at the airport, ask the name of his state (Utah), his religion (LDS), and ask him about Utah: how it was settled, the dominant religion. Eventually, the reporter would ask questions regarding the LDS policy toward blacks and the priesthood. Shriver offered Dwayne a stateside job as director of community relations.

News of the unequal priesthood policy of the LDS Church had reached the arena of international politics.

The Stilmars attended Dwayne’s lecture and found it interesting and beneficial. Lynn the law student did not attend the fireside. In 1992 the Church called Dwayne to serve as president of a mission in Africa.

In the elders quorum one Sunday, the topic turned to proselytizing blacks and Irving Kelly, former agnostic and adult convert, held up his hand. He had a sharp mind, ruminated before speaking, and maybe had no second thoughts about what he said.

Recently, a black coworker had told Irving he was looking for a church and asked if Irving had one. “I am a Mormon,” he said, and they talked church. Before the conversation ended, Irving had told his black colleague the virtues of the Seventh-day Adventist church and suggested he check it out. We expected surprises from Irving, but this dumbfounded us. Irving simply said he did not want the man to study our church and end up disillusioned by our priesthood policy.

I changed jobs and transferred from the Navy to the State Department, leaving behind Glen Roane, my only black friend. His daily influence had provided me with the capacity to build empathy for American blacks, who have been evolving from the ashes of slavery toward freedom since the 1860s. I saw evidence of their limited rights to schools, housing, and jobs based on race. This evidence seared my conscience into action and I joined a friend to seek signatures for open housing in Northern Virginia.

At one house the door opened and a familiar face invited me in—he was a member of the elders quorum in my new Arlington ward. My petition surprised him; he would not sign it, said the Church was against civil rights, and asked me why I was supporting it. Other Latter-day Saints had asked me too, and it made me, a believer, uncomfortable.

This elder probably reminded me that Ezra Taft Benson, an apostle, had alleged civil rights advocates were connected with the communist conspiracy. Since Benson had served eight years as Secretary of Agriculture under President Eisenhower, his opposition to civil rights gained national attention. I told the elder this was a matter of my conscience, and I knew that Apostle Hugh B. Brown and Seventy Marion Hanks also supported civil rights legislation. The elder still refused to sign my petition.

My friend Dee Henderson managed the critical issues program at the Agriculture Graduate School in DC and I attended some of his seminars. As he told me his story about civil rights leader Vernon Jordan, I could feel regret in his voice. On their way to Dulles Airport after a seminar, Jordan had said he could not understand the Mormon policy on blacks. Dee, a returned missionary and a PhD candidate in political science at American University, said he was a Mormon and he would try to explain the policy.

During his explanation, Dee realized he had never broached this topic with a black before. He told me the dynamics proved so different he lost faith in the logic he had used with whites. Dee left the airport humbled by his performance. He wondered what impact the conversation would have on Jordan’s opinion of the LDS Church and he vowed never to volunteer to explain this policy again.

During the break between my classes in economics in the evening, I often talked with a student who seemed on his way to a career in demonstrating, which caused him to miss classes regularly. He paid a buck a year to belong to the Socialist Party, and he also belonged to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. One day as I walked down the stairs to the diplomatic entrance of the State Department, I spotted his red head among a dozen other students staging a sit-in.

Since rumors abounded of a march on Temple Square in Utah, I broached the rumor with the demonstrator one night between classes. He said it was all talk to pressure the LDS Church into changing its priesthood policy; a grand march on Salt Lake City was not feasible. As he talked he said the Mormon doctrine of continuing revelation should facilitate the change, said this doctrine was unique, provided great flexibility and power, and he praised on. His degree in philosophy may have spurred him to examine ideas and to resolve social issues nonviolently.

Wednesday, August 28, 1963, arrived: the day of Martin Luther King’s March on Washington. Early that morning, I felt diffident as Carol and I left our two-bedroom row house at 13Z1 Hillside Drive in Greenbelt, Maryland. We did not encounter rush hour traffic as we drove our little ’61 black Beetle down the Washington-Baltimore Parkway toward the nation’s capital. The capital, almost free from traffic, conjured up a ghost town at midnight: quiet, eerie, tense.

Carol left me at the State Department building and drove on to the House of Representatives. My boss, Jack Owens, entered my office and said our building was closed for the day since it was less than a block from Constitution Avenue, the parade route. I had the day off or I could work, but only employees could enter our building: no contractors, no outsiders. I called Carol at Congressman Harding’s office. She had to work, so I wandered to Constitution Avenue and awaited King’s parade.

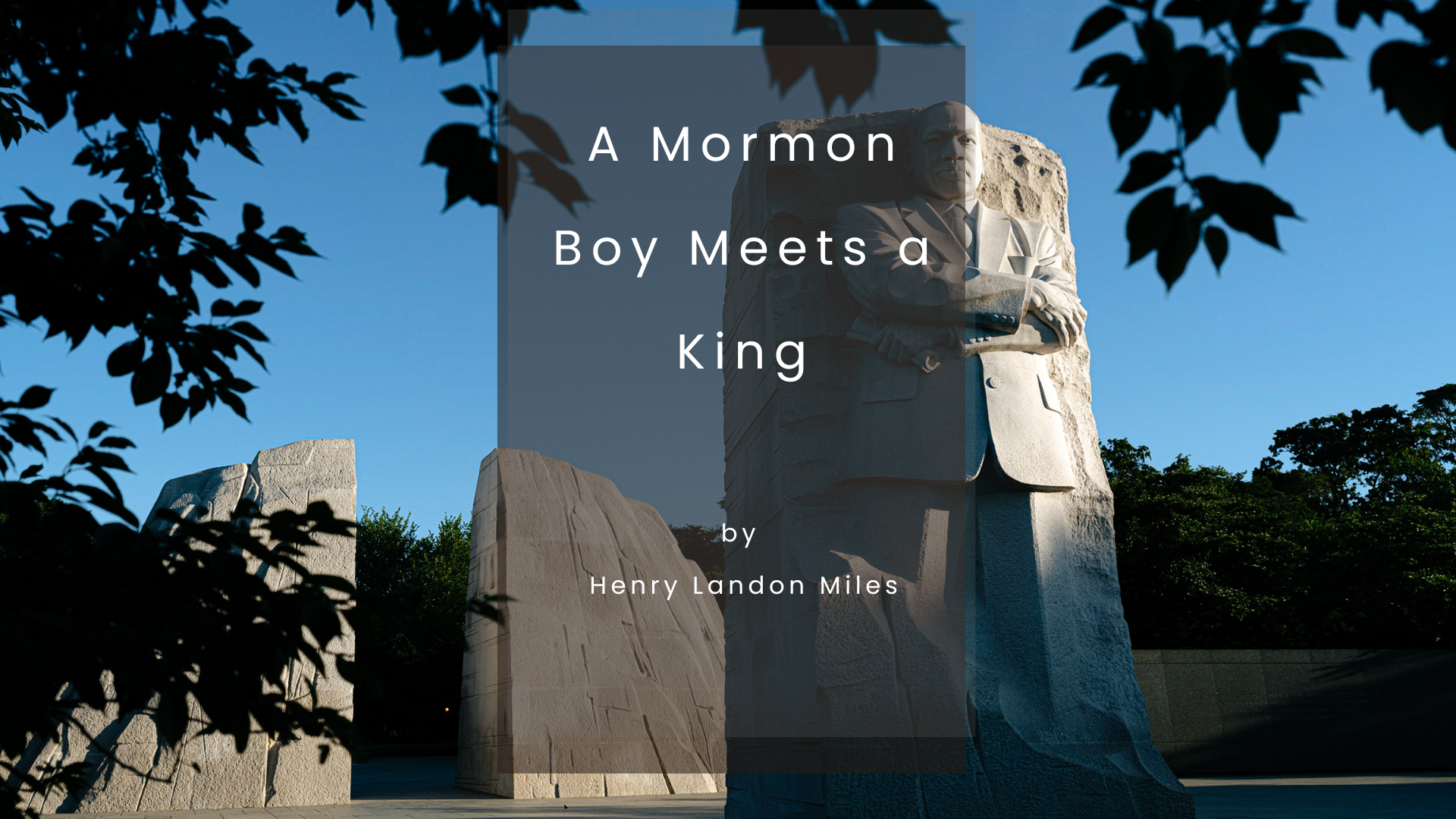

Standing at the curb as the parade approached, I saw a man break from the front row and run forward—toward me? I watched the figure as it turned into Glen Roane running. He shook my hand and said, “Join us.” Glen led me to the front row of the moving parade and introduced me to the leaders; Martin Luther King Jr. was in the middle. I shook hands as I walked among men I admired and said, “Pleased to meet you.” My debut done, I linked arms with two in the front row, one arm in Glen’s, and marched to the Lincoln Memorial. At the Memorial the parade diffused into individuals walking off in all directions and I lost Glen.

I stood watching and listening to the program in a white shirt, dark suit, and tie. I watched King prepare to give his speech. People were gathering to listen to him, the largest, most diverse group of humans I would ever see. The reflecting pool and Washington’s obelisk were at my back as I gazed at Lincoln’s statue and meditated. For this event, was Lincoln’s consciousness able to enter his statue, nineteen feet tall, carved of twenty-eight blocks of white Georgia marble, sitting in an uncomfortable stone chair, his hands forming an “A” in sign language?

Thinking from 2019 back to King’s dream, I imagine what God foresaw that I could not. I did not realize Glen’s influence on me; I did not know King was leaving his prepared speech to preach his oft-repeated message, “I have a dream”; I did not know I was hearing the best American speech of the twentieth century. I did not foresee King’s death in less than five years, did not see Glen and I joining the Foreign Service, serving in embassies around the world but never together again. I did not foresee myself serving more than eleven years in Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and El Salvador, and my family helping to establish the first LDS mission in each of the first three of these countries.

And what pleases me most that I could not then foresee? Apostle Spencer Kimball would live with us for a week in La Paz, Bolivia, and learn of my career problem: my mother-in-law wanted our family to stop living abroad and settle near her in Blackfoot, Idaho. Kimball’s letter to her dated 6-6-66 said the Church needed more families like her daughter’s to work abroad and support missionaries and converts, and our being in La Paz seemed “quite providential.” She complained no more: the Foreign Service became our career, and the letter became her keepsake.

And I did not know that Apostle Kimball would become president of my Church and stand tippy-toed on the branches of the bush that had refused to bend, reach his hand way up into heaven in 1978, and grasp a scroll that read, “Give my priesthood to all worthy men.”

Moreover, I did not foresee what must have pleased Glen Roane most: his state of Virginia, repenting for Glen’s pain at the bar exam and passing House Joint Resolution No. 340 in February 2012, celebrating the life of Glenwood Roane shortly after his death.

WHEREAS WHEREAS WHEREAS

RESOLVED by the House of Delegates, the Senate concurring, That the General Assembly note with great sadness the loss of a distinguished and singularly accomplished Virginia native, the Reverend Glenwood Paris Roane . . . .

Back to August 28, 1963. King’s speech ended and I found myself baptized in emotion, immersed in feelings of peace still flowing from “I have a dream.” I found myself wandering east along the reflecting pool toward the Washington Monument in a sea of humanity, no destination in mind, found myself alongside an old black man in coveralls, a cap, and knee high rubber boots, swinging a radio as we walked along, listening to music on station WAVA.

The music stopped for news and both of us heard, “The march on Washington is turning out as peaceful as a family picnic on a Sunday.” The old man said, “That’s just the way we wants it. That’s just the way we wants it.”

And we became one.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue