Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 4

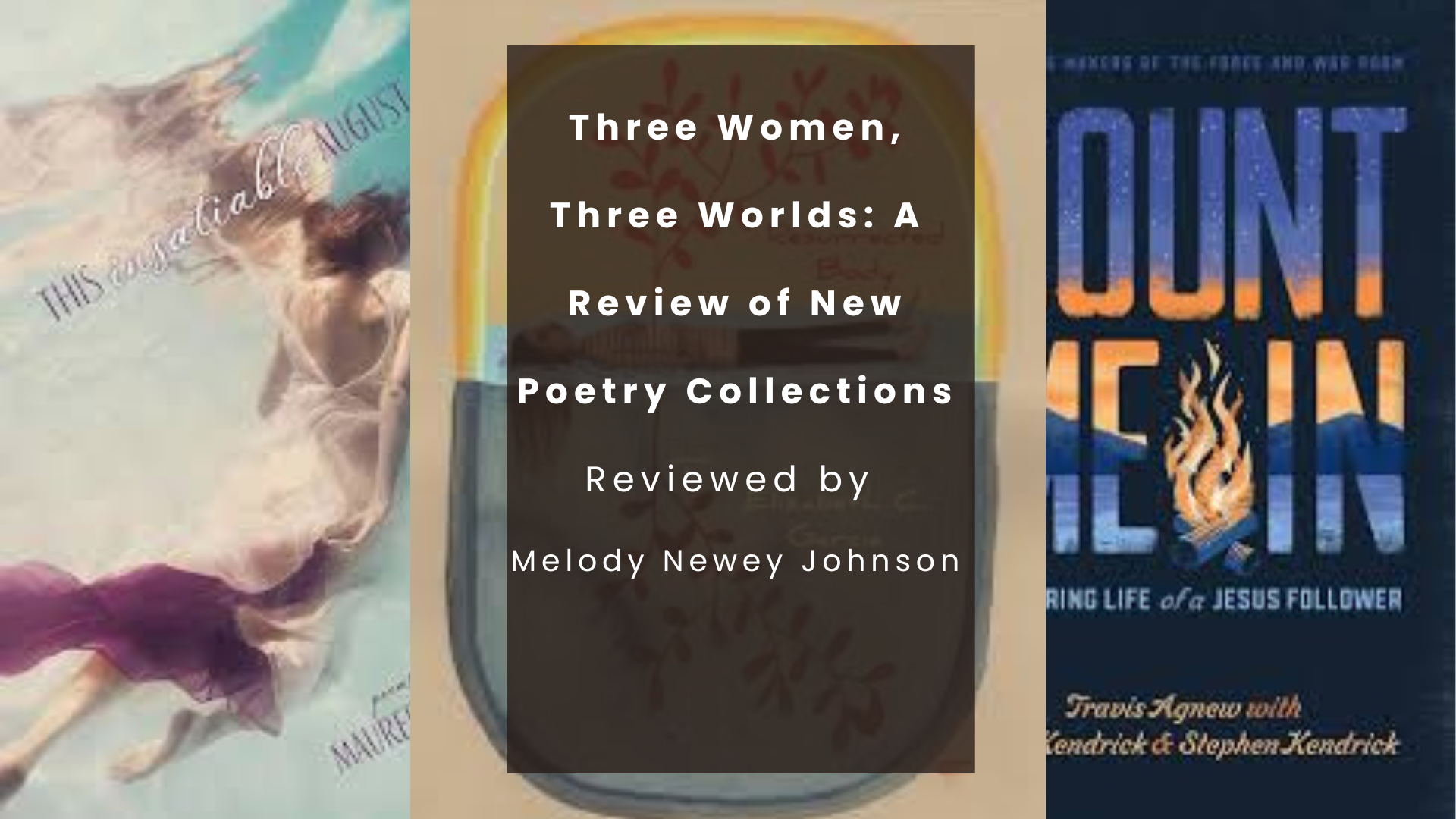

Three Women, Three Worlds: A Review of New Poetry Collections | Maureen Clark, This Insatiable August; Elizabeth C. Garcia, Resurrected Body; Darlene Young, Count Me In

It was a pleasure to read and review recent poetry collections by Darlene Young, Elizabeth Cranford Garcia, and Maureen Clark. Each poet in her own voice and with her own hand dissects, examines, and elucidates themes of relationship, selfhood, parenthood, God, and nature. Collectively they create a kaleidoscope of experiences from women in different but overlapping stages of life. Reading them as a tryptic feels like visiting a collaborative art exhibit by the likes of Judy Chicago, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Joan Mitchell—beauty everywhere and something for everyone.

Reading Darlene Young’s collection, Count Me In, feels like an invitation into your best friend’s backyard where the whole neighborhood is playing night games and improvising backyard theatre: it is well-organized and full of energy. Young is an accomplished writer—both succinct where it matters and also willing to tell the story the poem demands. Her poems illuminate our favorite humans in a generous and sometimes stark light. She is honest and clear when writing about her own life and about other imagined lives.

In the opening poem, “The Baby That Became Me,” Young describes the sublime beauties of the newborn who “had not yet met her lifelong bully—her older self” (2). From this compelling introduction she traverses childhood, adulthood, and all parts in between. In “Motherhood,” the poet as a child sees her mother as the expansive sky and herself as “a small bird dark against her” (11). Later in the poem, Young has become a mother herself and embodies the burden of motherhood as she speaks to her child: “you fill my sky / sometimes I can’t even see daylight at your edges / at night I stare into the dark / and gasp for air” (11).

Young lends equal gravity to poems about the life of a teenage boy coming of age and the imagined loneliness of the prophet Moroni. She also conjures the singular experience of Lazarus after he was raised from the dead in the haunting and magical “Lazarus 2.0.” The subject navigates a strange, renewed existence where “The words got stuck in his mouth, as if in a second language, as if overrun by some distant music.”

The reader may most acutely observe Young’s skillful crafting of language and her love of words where she strings words and phrases together in several list poems. In these she leads you, the reader, down a path to either a wonderful surprise or to the bottom of a dark well where you’re not sure how to climb out—or if you even want to. (See “Hinge,” 22; “What I Hope My Children Will Say on Mother’s Day in 30 Years,” 36; “Things I Have Pretended,” 38; “Things I Have Lost,” 56.)

Several poems in this collection, including my current favorite, “Morning,” demonstrate Young’s ability to find a thread of glory woven through ordinary life. She tugs the thread out until it glimmers just enough to give the reader a measure of hope they didn’t know they needed, “. . . and feels herself part of the tree, the call / the yellow morning, even here / in this nondescript suburb, which is, she knows / actually, a pretty good place, as holy as any” (54).

Elizabeth Cranford Garcia’s Resurrected Body is an aptly titled ode to incarnation. Animal, vegetable, and mineral are all enlivened through Garcia’s unflinching storytelling. In the introductory poem, “What to Expect When You’re Expecting,” she invites us to dive into flesh and bone. “You will be spatchcocked / your sternum, your backbone scissored out” (xiii). Here Garcia meets herself and the reader in her extremities and continues to do so throughout the book. She offers equal grace to her childhood memories of the sounds of a ’72 Datsun, her mother’s crush on Tom Selleck, her father’s cardiac arrhythmias, and what a deer might see in the forest or when captured in approaching headlights, “where the fractals of all your possible selves // branch out forever, and she stops to wonder / which one you will choose” (44).

Garcia’s four “Self-Portrait as Sinkhole” poems are stunning. The poems are interspersed throughout the collection. For the reader they may act as unexpected anchors into a deep and mysterious connection with Mother and Earth. Among my favorite images within these poems were descriptions of the quiet workings beneath the earth’s surface and then the inevitable human reunion with soil: “just how little acid water needs / to carve its runnels / into memory like lace” (21). And later in the poem, “you who were not the child self // were falling your mouth wide open / face down your mouth filling with dirt / and dead leaves—you / are the mouth. You / are the swallowing, becoming it” (22). And the beautifully descriptive lines in another sinkhole poem: “And in its belly, metal chairs, broken bottles / the night offerings of teens baiting nature, uprooting // whole systems of belief—what is the seismic cause / for all that gives way beneath us—mothers / in their beds, frail as bird bones, cousins / drowned, uncles, wood-stemmed, still whittling away” (36).

The author paints intimate portraits of motherhood, sometimes darkened by postpartum depression and always warm and honest. Some poems may be personal, maternal memoirs, but she does what great poets do: She finds the right words to express the inexpressible for the reader too. In “Shit Mom,” Garcia speaks as the desperate mother of young children where the subject may believe she “deserves the flock of sharp-winged women / their stormswift their I-would-nevers / clawing her to eternal torment” (16). And every woman who has ever nursed a baby will see herself in the poem “Full,” with “milk-hard breasts, wheelbarrows / heavy with river rock. / This is the weight of mercy, / the body’s need to empty itself, / to fill another” (59).

Maureen Clark’s debut collection, This Insatiable August, feels like a celebration of Everything. Clark is a consummate writer who employs classic and freeform verse to transform everyday moments into high art. In so doing, she grants the reader permission to see life clearly—as it once was, as it is now, and as it may be—and to embrace it all, including the messy bits.

The introductory poem, “Sunday Song,” is brief, sublime, and by the fourth line is thick with portent: “Wind is worrying something into shape. Is it a boat or an axe?” (1) From there Clark moves to a poem envisioning her ideal heaven—in “Most of All a Future,” she asks, “What’s the point of paradise without orange-sections and sunsets?” (4) And later, “What can recommend mortality except the bite of winter // and the sweet return of birdsong, a letter arriving from a future tense? / I want the splinter so it can be removed. And gloom, / I want all the green at once, memories of imagined lovers and loss” (4).

Clark includes several beautiful pieces about lovers and loss in this book. In “Circumstance,” a poem about a long marriage, she asks, “How could I unknot the intricate tatting of what we share // undo the web of finely woven rituals of our youth, / the tiny knots we made to hold, to last” (6). And in the end, “Yours is the only death / that would turn me entirely thorn.” In another poem she paints a vivid picture of the place on the bed where a lost beloved has slept. “The feather pillow keeps // the impression of your head, as though gravity / still has hold of you, as if the shelter / of your body were just there . . .” (7)

The poems move with Clark through a maturing spirituality, one that ultimately leads to a loss of faith in God and in the religious home she had known since childhood. But the heartache and loss may be softened by the presence of the author’s ancestors. Clark’s poems about her mother, father, grandparents, and great-grandparents are wonderfully tactile—from a root cellar to a turkey slaughter to her mother’s illness. These are real, complex, and comforting characters in the story. Additionally, the author’s own four “Psalms” pepper the journey with something akin to hope.

My current favorite in this collection is “Knotted Wrack,” an iconic declaration by a woman becoming herself, “just a woman who is naming herself one letter at a time a woman / who lives in a kind of poverty so rich I can be full / of questions. My feet are bare. I carry a jar of ointment. I am a traveler / looking for answers” (66). Among her readers Clark will no doubt find a congregation of women shouting “Amen!” to this poem.

Readers will return to these collections again and again for their varied and brilliant witness of the lives of women, for the wisdom they impart, and, perhaps, for unexpected kinship with the authors in their respective worlds.

Maureen Clark. This Insatiable August. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2024. 84 pp. Paper: $14.95. ISBN: 978-1560854739.

Elizabeth C. Garcia. Resurrected Body. San Diego: Cider Press Review, 2024. 100 pp. Paper: $18.95. ISBN: 978-1930781658.

Darlene Young, Count Me In. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2024. 82 pp. Paper: $14.95. ISBN: 978-1560854746.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue