Articles/Essays – Volume 58, No. 1

Armenians and The Church of Jesus Christ ofLatter-day Saints: A Hauntological Exhibit

Listen to an interview about this piece here.

From 1986 to 1993, I was history curator at the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City, Utah. In the spring and summer of 1993, I was preparing an exhibit on the story of Armenians who joined the LDS Church in what is now Turkey and Syria between 1884 and 1928. This forty-four-year period covers the beginning of the Church’s mission to Armenians, the creation of congregations and church programs, and the travails of persecution and emigration. It ends with the death of Joseph W. Booth, the long-serving missionary to Armenian Saints, and the termination of Church efforts to create an “Eastern Zion” with Armenian Saints dedicated to cooperative agricultural and light industry. It was, and remains, an important and moving story of religious faith, persecution, genocide, rescue, emigration, culture, and perseverance. The Armenian Mormons in Utah whom I met and worked with thirty-plus years ago were generous with their stories, historical photographs, documents, artifacts, and samples of their skilled weaving and needlework. They looked forward to seeing the story of their ancestors and culture featured at the museum and in print.

It was a grievous disappointment to them (and me) that the exhibit, well into the planning stages, was canceled. I recall being told that shelving the exhibit was due to “politics”—I was told the Church was in secret negotiations with the Turkish government. An exhibit about Armenians at the museum during the late Ottoman era and the early years of modern Turkey was a no-go.

Thirty years later, I feel I still owe a debt to the Armenian Mormons who entrusted me with their stories and artifacts. I want to take what remains of that exhibit—the words written thirty years ago and a handful of photographs—and share them with readers of Dialogue. Consider it an example of hauntology: the enduring presence of elements from our social and historical past that abide as in the manner of a ghost. (Coincidentally, in 1993, Jacques Derrida coined the term “hauntology” in his book Specters of Marx.[1])

A history museum exhibit staff—the curators and designers who build the displays and create educational materials for docents and the public—strives to tell an important story from the past, one either unknown to most of the public or in need of retelling and reinterpretation. They do this through the display of artifacts, maps, photographs, interpretive wall texts, dioramas, documents, exhibit catalogues, and other media.

It must be said that there is no such thing as a neutral curatorial position in any museum. This is even more true for those professionals working for the Museum of Church History and Art, now called the Church History Museum, in Salt Lake City. While each member of the staff was dedicated and qualified in their respective professions, our many tasks in the museum were informed by and committed to both professional excellence and faithfulness to the Church and its mission. The outcome? As a museumgoer, you could get the straight story about the Perpetual Emigration Fund and nineteenth-century oceangoing Saints but not a word about polygamy. You could marvel at an exhibition of the skills of the architects and the artisans who built the Salt Lake Temple, but there would be no mention about the exclusion of Black members from the priesthood and, therefore, their exclusion from the work and sancta of Mormon temples until after 1978. And no exhibit about Mormon Armenians in 1993–94 due to “politics.” It could be—it was—a hard line to walk as a professional historian with a mandate to also promote the Church and its mission faithfully as expressed by Church authorities in the 1990s. The cancellation of the Armenian exhibit was a salient reason, though not the only one, that I stopped working for the Museum of Church History and Art in the fall of 1993.

Moving an exhibit story idea from conception to completion takes a number of steps or phases. What follows below is a version of the “Phase II Review” text of the projected Mormon Armenian exhibit submitted to the museum administration and the LDS Church Historical Department. What’s missing is the rest of the exhibit process and thus the exhibit itself. The collection of artifacts, photos, and documents, the research and writing, the exhibit design and the fabrication of display cases and artifact mounts, the placement of maps, narrative wall texts and artifact labels, docent education, catalogue production and publicity—all of it came to an unfortunate, premature halt. We had hoped to open the exhibit at the end of 1993 or in the early months of 1994. The working title of the exhibit was “The Exodus of the Armenian Saints.”

In history museums, everyone, curators and museumgoers alike, must use their sympathetic imagination in order to bring an exhibit alive with meaning and affect. In this case, this hauntologial exhibit, there is the ghost of an exhibit that should have been. Today, there are no artifacts, documents, maps, labels, graphics, and final narrative wall texts to display. It will be up to the reader to imagine, to picture in their mind’s eye, what might have been.

The Armenian Saints I visited with in 1993, so pleased to share the stories and prized historic artifacts of their families and all that they had gone through for sake of their faith, have all passed away. I’m the older person now, still feeling the loss of an exhibit that never was.

July 28, 1993

Phase II review

The Exodus of the Armenian Saints

A. Development Schedule

Phase One: May 12, 1993—An opening statement justified the exhibit, with projected staffing needs and a budget estimate. A working title, interpretive focus, and narrative content, as well as preliminary research, were presented for review and approval.

Phase One approved.

Phase Two: July 28, 1993—Identified and outlined the overall and section-by-section objectives. This phase also included a narrative outline of the introduction and the major exhibit sections. Most artifacts, maps, photographs, and documents had been collected for display.

The exhibit is cancelled.

(Phase Three: October 27, 1993—Would have included the final collection of artifacts, photos, and documents. Graphic elements and design features would have been presented. Preliminary texts for titles, wall-mounted panels, and all artifacts, etc., would have been submitted for review and approval or reworking.

Phase Four: December 22, 1993—The complete exhibit proposal for texts and design would have been given a final reading. If approved, the exhibit would have moved into production with a tight schedule for completion.)

B. Interpretive Framework: Objectives and Narrative

Objectives

The principal objectives of this exhibit are to tell the story of the conversion and faithfulness of a group of Armenians to the Restored Gospel; their lives in Ottoman Turkey and Syria; the catastrophe that befell all Armenians in Turkey (1915–21), including LDS Armenians; and the Church-assisted exodus of surviving LDS Armenians from Aintab,[2] Turkey, to Syria in 1921.

Additional objectives support this goal;

underline the extensive scope of the missionary vision of the Church and of the universality of the gospel (a working theological and historical assumption of other international Church exhibits).

demonstrate that the rescue of the Armenian Saints from Turkey in 1921 is best understood as Mormon Armenians themselves understood it—through the paradigm of the biblical Exodus narrative.

introduce Joseph W. Booth as a principal agent in the rescue and reconstitution of the LDS Armenian community in Aleppo, Syria, 1921–28.

explain that LDS Armenians wanted to gather with the Saints in Zion, that many of them emigrated to the United States, and that they continue to preserve their Armenian cultural heritage.

Objectives of the seven exhibit sections:

- 1. introduction/setting and context: Museumgoers will be introduced to learn an unknown and important story in LDS history. They will locate Turkey and Syria and Armenians within it, during the period from 1884 to 1928. Wall texts provide a basic orientation to site, history, and culture.

- 2. LDS mission to the Armenians: The Church’s extensive vision of evangelization included the Ottoman Empire. A small, but significant number from the Armenian minority community embraced the gospel. Branches were organized, members were persecuted because of their LDS faith. Missionaries and Church leaders sought for years to establish an agricultural/light industrial “colony” for Armenian members to lift them out of poverty and strengthen their religious faith. Names and faces of missionaries and members will be introduced.

- 3. the catastrophe: Turkish governments singled out the Armenian people for extermination/deportation between 1915 and 1921. Armenian LDS shared this nightmare with the wider Armenian population.

- 4. the survivors reassemble: Aintab and Aleppo, 1918–1921: LDS Armenian survivors of the war and genocide regrouped in Aintab, Turkey and Aleppo, Syria; French troops occupied this area but announced their retreat from Aintab. The Saints in Aintab were in grave peril once more due to Turkish efforts to “ethnically cleanse” the region.

- 5. the rescue from Aintab: The Church worked to rescue members of the Aintab branch in November–December 1921. This is a dramatic story best perceived, as it was by Armenian Church members, as a modern-day “exodus.” Joseph Booth, under the direction of Elder David O. McKay, was the Church official responsible for rescuing members of the Aintab Branch by relocating them in Aleppo, Syria.

- 6. Mormons in Aleppo: These Saints strove to be economically self-sufficient and to create a fully viable religious community. Thereafter, many surviving Armenian LDS emigrated to the United States.

- 7. keeping faith: Finally, the exhibit will show that Armenian Latter-day Saints live and worship among us and strive “never to forget” their heritage.

Working Title: The Exodus of the Armenian Saints Narrative Outline

Exhibit Section 1. Introduction, setting and context:

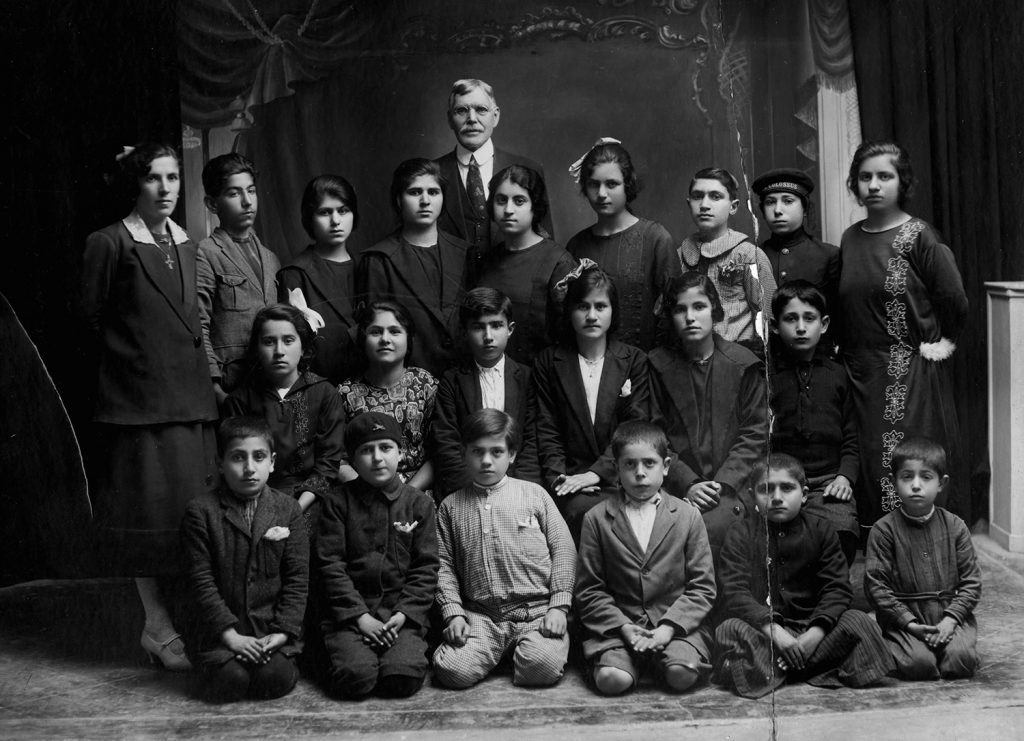

Two photographs of the Aintab Branch will be exhibited. The first shows branch members in about 1908. The second repeats the first but with faces of those members killed in the Armenian genocide blacked out. An accompanying text identifies the branch, states that approximately 1.5 million Armenians were killed as part of Turkish government policy, that Church members shared the fate of their people, and that in 1921, imminent peril faced the survivors of the LDS Branch in Aintab.

With a map of Ottoman Turkey and Syria, along with period engravings of Anatolia, of Turks, Kurds, and Armenians as visual aids, a brief text provides background information and context for the story of the catastrophe facing Armenian communities in the Ottoman Empire circa 1885–1915.

Exhibit Section 2. LDS Missions to the Armenians:

a. Beginnings:

The Church sent missionaries to Ottoman Turkey as early as 1884 in response to inquiries about the Church and as an expression of the extensive missionary effort in the nineteenth century to gather the Saints to Zion. While some Church leaders entertained hopes of making inroads into the Muslim and European populations, the only group to manifest interest to the restored gospel was a number of Armenians living in central Anatolia and to the south in Cilicia.

October 3, 1888. “There came [to Zara, Turkey] a Mormon missionary by the name of F.F. Hintze . . . I went with the others and listened to him and asked many questions concerning the principles of the Gospel and he answered everything to my satisfaction. I also returned the second and third night. We were so interested that we remained until midnight . . . and we could hardly take our leave of him . . . Before I left to come home this very night, I asked him [Hintze] one last question: “So far as I understand, your words are all true, also your church is better than all other churches, for I have been seeking this thing all my life, and am willing to become a member of your church, but how do I know that you are an authorised elder and sent by God to preach His Gospel?” Then he said to me, “brother Sherinian, I cannot give faith to you, faith comes from God. Go home and read John 7:16–17 and you will know the “doctrine whether it be of God or whether I speak for myself.” (from “History of Nishan Krikor Sherinian, Emigrant from Zara, Sivas, Armenia to America 1902 . . . “ LDS Church Archives)

b. Organization, Persecution and Response:

Between 1885 and 1896 and in 1898 to 1909, missionaries organized five branches. During this time, some two hundred adult Armenians joined the Church. They faced tough persecution from their fellow Armenians in the form of physical threats of violence, disruption of Church services, evictions from their homes, dismissal from jobs, loss of income, etc. In response, Church members learned Persian-style rug making and Armenian lace craft in an effort to become economically self-sufficient. For many, to be Mormon in their everyday lives meant making rugs and fine needlework. In addition, they met frequently together in lively church meetings and study groups.

“We tried to hold meetings, which was difficult, but we held them for several years. As members we would go to church [and] people would stand on the side of the road and throw sticks and stones . . . This went on for quite some time.” (from George Z. Aposhian, Oral History Program, Interview, 1972. LDS Church Archives)

“They had a hard time finding work because they were Mormons. They were the last ones hired and the first ones fired. It was at this time the missionaries solved the work problem. They sent Artin Ouzounian to Aleppo, Syria to learn the Persian style of rug weaving. He came back to Aintab and started a business. The members of the church learned the trade from each other. Soon, most of the Aintab branch became self-employed. (from Melva Emrazian, “Moses Hindoian Family: Early Trials and Conversion”)

May 20, 1894. “Meetings have continued as usual with Bro Herman generally speaking in the morning session and the Saints the afternoon session each Sabbath. Thursday evenings are occupied in testimonies by the Saints.”

December 17, 1899. “Found the affairs running nice under the management of Armanag Shil Hagopian, both Sunday School and Sacrament meetings, and the Saints feeling very well.” (Record of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Aleppo Branch, Turkey, LDS Church Archives)

June 21, 1899. “YS [Sisters] MIA organized. It is hoped that the dawn of women’s rights and advancement has burst upon this unenlightened land. Truly the gospel is able to work us wise unto salvation.” (J.W. Booth, Diaries, BYU Archives and Special Collections)

c. A “Colony”:

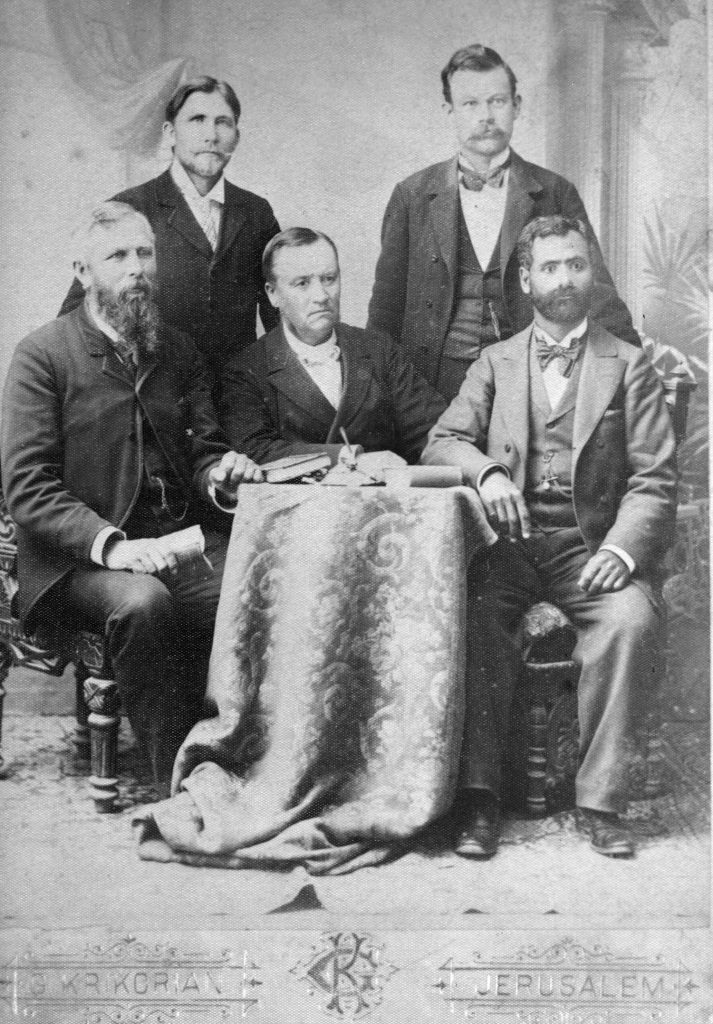

Church leaders Ferdinand Hintze, Joseph Booth, Dr. Arminag Hagopian, and others, wanting to improve the vulnerable economic and spiritual condition of Armenian Latter-day Saints, proposed organizing the Saints as an agricultural and rug-making cooperative. In 1898, Elder Anthon Lund traveled to Ottoman Turkey and Palestine to explore the “colony” idea with Church members and identify a tract of land on which to settle the Saints in a pattern like gathered LDS communities in the American West. Lund, Hintze, Booth, and others continued to champion the idea into the twentieth century. These efforts were never realized.

Figure 3: The Armenian “Colony” Delegation from left to right: Ferdinand Hintze, Philip Maycock, Anthon Lund, Andrew Larson, Nishan Sherinian. On the occasion of this photograph, taken 9 May 1898 in Garabed Krikorian’s studio near the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem, Larson wrote: “Dusted our old clothes, brushed our shoes, twisted our moustaches and went to the photographer and had our pictures taken.” Larson, Reminiscences and Journals. (Photograph Church History Library and Archives)

April 23, 1898. “The country we wished to see lay on the west of the plain of Jezreel and extended into the plain as far as the River Kishon. . . .We are all very well pleased with the land and thought the location splendid.” (Andrew Larson, Diary, LDS Church Archives)

This was the El Kireh property surveyed by Lund and his colleagues. Some 6000 acres, it was deemed sufficient for settling the Armenian Saints in an “Eastern Zion” on several town sites for farming and light industry. In a letter to Hintze, Elder Lund reported, upon his return to Utah, that Church officials had approved their final report. However, due to the Church’s indebtedness in 1898, they had concluded “the time had not yet come to buy the land.” “We will not always be so poor,” Lund asserted. (Ferdinand Hintze, Papers, LDS Church Archives)

A subsequent “colony” project approached realization in the spring of 1909 when LDS missionary Elder Page reported favorably to the First Presidency about several tracts of land near Aintab and Aleppo and proposed an agricultural plan to gainfully occupy the Saints.

March 22, 1909. “We have to report that President Booth is very anxious to have a project of this kind started as early as possible; and that the Armenian members of the Church are in most cases in very destitute circumstances.” (Elder Thomas Page, “Report to the First Presidency,” LDS Church Archives)

However, rioting broke out April 15, 1909, and massacres decimated the Armenians in the Cilician port of Adana and the surrounding regions. The colony proposal was scuttled; missionaries were sent home, and Armenian Church members were left to manage their own affairs as a greater catastrophe was soon to descend upon Armenian communities throughout Ottoman Turkey and Syria.

Exhibit Section 3. The Catastrophe

Radical Turkish nationalism: A coup in 1913 brought to power a clique of radical, nationalist military officers. The “Committee of Unity and Progress” (CUP), the junta’s political/ideological party, pressed for a revolution of Ottoman society based in a three-part program:

re-education and assimilation of minorities as Turkish, not Ottoman citizens; identity based on nationality, not religion/ethnic community.

creation of a “greater Turkey,” which entailed: (a) an independent state with absolute sovereignty over its external and internal affairs, (b) elimination of the Armenian presence in Anatolia; that is to say, the deportation and/or death of nearly two million people.

unity of all “Turanians” (an idealized racial identity, like the Nazis’ “Aryans”) from Asia Minor to the Mongolian steppes in a Turkic-speaking super state.

The hostilities of World War I gave the CUP the pretext for carrying out their plans. In World War I, Turkey allied with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire against England, France, and Russia. Warfare broke out on Turkey’s eastern border with Russia. Declaring Armenians a “fifth column” within the state, the CUP ordered the mass deportation and annihilation of the Armenian people in Anatolia and Cilicia. Beginning in 1915, Armenian communities were assaulted, men and adolescent boys were murdered outright, property was confiscated, and women, children, and elderly people were force-marched toward concentration camps far to the south in the northern Syrian desert. Most of those who survived the deadly trail died in the camps. LDS Armenians shared their people’s fate. LDS branches in Zara, Sivas, and Marash ceased to exist. Many of the members of the branches in Aintab and Aleppo were killed.

A map of Turkey, with reproductions of the headlines of period newspapers and testimony of surviving Mormon Armenians will graphically narrate the events.

“In 1915, the Turkish government embarked upon a program of mass extermination of the Armenian people within Turkish held areas. . . . In this terrible time, all the Aintab Presidency lost their lives, as did a great many of the members . . . There was little food and clothing for the members. . . . At times, the people had to eat the leaves of trees.” (from Reuben Ouzounian, “Autobiography,” LDS Church Archives)

“That terrible massacre took place in all Turkey. . . .The rest of our relatives and friends all perished in that massacre. Zara our beloved birthplace was drenched in blood.” (Arick Sherinian)

“This is the story of their suffering and death.” Elder Joseph Booth hears about the fate of the twenty members of the branch in Marash from its sole survivor. “Aintab the beautiful city of so many years of my missionary experiences is now in ruins.” (J.W. Booth Diaries, BYU Archives and Special Collections)

“How can the Armenians ever forget what they went through, to the last generation, all they suffered for their Christianity . . . even if it cost them their beloved land and their lives?” (Arick Sherinian)

Exhibit Section 4. The Survivors Reassemble: Aintab and Aleppo: 1918–1921

Under the direction of Moses Hindoian, a small group of LDS Armenians in Aintab who survived the bloody years of war attempted to reconstitute themselves as a viable unit of the Church. Brother Hindoian contacted Salt Lake City, informing Church headquarters of their survival, their life at the edge of subsistence in postwar Cilicia and their need for material assistance and missionaries.

Figure 4: Moses Hindoian (upper right) with Joseph and Reba Booth and some members of the Aleppo Branch, ca 1922.

French troops occupied the Cilician area, which included Aintab, in the wake of the defeat of Ottoman forces in 1918. Their goal was control and colonial administration of the region. However, they lacked sufficient military and logistical strength, as well as popular goodwill, to achieve the postwar mandatory power granted them in the Versailles Treaty. Turkish national armies and militias forced the French out of one city after another in Cilicia. The story of the French Mandate from 1919 to 1921, in what is now southern Turkey, is one of prolonged retreat.

In the late summer of 1921, French negotiators agreed to surrender their claims to Aintab and to accept the secured borders between what is now Turkey and Syria. This agreement exposed the Armenians of Aintab to the Turkish policy of what we call “ethnic cleansing.” The prospects of the remaining Saints in Aintab were grim.

Exhibit Section 5. The Rescue from Aintab

Moved by the communications from the branches of Aintab and Aleppo, the LDS Church’s First Presidency called Joseph Booth, who had already served nearly a decade of missions among the Armenians, to return, assist members, and build up surviving Church branches. On November 4, 1921, Booth met Elder David O. McKay near Tel Aviv, and together they traveled to Aleppo and Aintab. Seeing the perilous state of the Saints in Aintab, McKay told Booth to organize the evacuation of members of the Branch to Aleppo. The rescue of the Saints has taken on mythic proportions to those who participated, witnessed, and reminisced about the events of November–December 1921.

(Benjamin Almagian brings word from Aintab.) “Fear, anxiety, threats, pleadings for passports, dread of a great calamity seem to hang over the city.” (J. W. Booth)

November 30, 1921 “In Aintab the Saints are fearful of their lives as threats are reported of grave dangers of another massacre if the French withdraw and leave the remaining 7–8000 Armenians in the hands of the Turks. We are constantly praying for the Lord to open the way for them to escape.” (J. W. Booth)

December 1, 1921 “I felt impressed to secure a conference with the French General DeLamathe and ask him to grant permission to bring the members of our church with their relations and friends from Aintab to Aleppo.” (J. W. Booth)

“ General DeLaMathe of the French army issued orders for 53 passports for all the Mormons [passports weren’t required for the children] to come out of Aintab, and also ordered the officials to assist me in getting them to Aleppo.” (J. W. Booth)

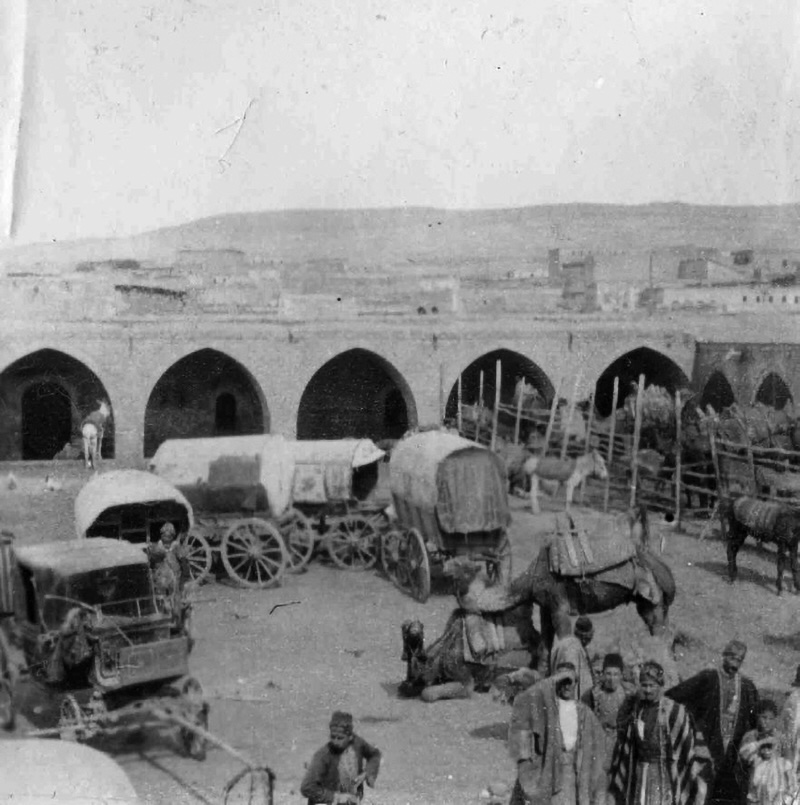

Figure 5: The Convoy of Wagons Assembles in Aintab. (Church History Library and Archives)

December 7, 1921 “In late afternoon I called at the passport office. The whole court below was filled with hundreds of people anxiously waiting . . . The roar and tumult of the crowd was hushed when about 150 names were read out . . . and then the words, “Now come the Mormons” was followed by the reading of names on my list which ended the passports issued today. Within a few minutes papers were in the hands of Bro Moses Hindoian . . . Mormons were famous in Aintab today.” (J. W. Booth)

“All of the members of the Aintab Branch were evacuated for Aleppo on ten horse carts. The journey from Aintab to Aleppo took three days.” (“Short History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Middle East,” from The Journal of Mary B. Ouzounian)

“The picture shows the convoy on their way to Aleppo. The big covered wagon is the one in which I traveled, and slept at night. In a few days we were all safe in Aleppo.” (J. W. Booth)

The “Exodus” Remembered

“This exodus of the Aintab members has been looked upon by the members of the Church in the Near East as the greatest event in the history of the Church in the Near East. During the following years, its anniversary was celebrated. Stories and poems were written to immortalize it. . . .to remind the members of the goodness and mercy of God in their deliverance, just as the exodus of the children of Israel from Egypt was as by later prophets.” (Rao Lindsay, History of Church Missions in the Near East, LDS Church History Library.)

Figure 6: Convoy to Aleppo, December 1921. (Church History Library and Archives)

Exhibit Section 6. Mormons in Aleppo

a. Booth and Religious Community, 1921–28: Joseph Booth spent the rest of his life in Aleppo working with the Saints: organizing auxiliaries of the Church, sponsoring writing and reading contests, attending to their material needs, striving, still, to preside over the creation of a “colony” for the Saints. The death of Booth in 1928 and the final rejection by headquarters of a Church-sponsored “colony” brought a nineteenth-century-oriented Mormonism in the Levant and Cilicia to a close.

April 11, 1922. “In the afternoon meeting Bros Hagop Bezjian, Moses Hindoian & Nazar Bezjian were ordained Elders. . . . Sacrament was administered by Moses and Nazar. Hagop offered the opening prayer& each one spoke with a humble spirit. It was indeed a day of great rejoicing.” (J. W. Booth)

December 24, 1922. “The Officers & Teachers of the relief society met in my room this evening to consider the conditions of some of the poor who needed clothing and made some decision as to whom they should help. I instructed them to begin with the most destitute of the Saints—that is the younger children & Sisters.” (J. W. Booth)

“President Booth hired Miss H. Hundakdjian to teach us to play the violin. There were twelve boys and girls who learned to play. We even formed a small orchestra and played several times.” (Mary B. Ouzounian)

Figure 7: Members of Aintab and Aleppo Branches together, Aleppo. 1922. (Church History Library and Archives)

April 14, 1925. “MIA—the young people presented a Drama, ‘An Armenian family of the Deportation 1915’—written and prepared by Garabed Junguzian and Kevork Nersisian etal. It was a very credible play. An audience of nearly 300 crowded into the open-air yard to witness the performance.” (J. W. Booth)

August 1, 1925. “The name of the Drama was changed from ‘Nephi’ to one they thought would be more suitable for the public here and the handbills read “The Death of a Drunkard and 5 Marriages in one night” and took up the events in the life of Lehi and Nephi to the joining of the family of the fleeing Prophet with that of Ishmael. . . . We had about 400 present.” (J. W. Booth)

b. To be a Mormon in Aleppo:

Economics: The Saints continued to strive for economic viability through lace and rug manufacture. Melva Hindoian recalls that “to be a Latter-day Saint meant making rugs and lace.” Reuben and Mary Ouzounian eventually owned fifty looms and employed one hundred and fifty people, many of them members of the Church, making rugs throughout the Armenian quarter in Aleppo.

“Most of the Mormons lived on a large property of about three acres on Yabel Nahur Avenue . . . acquired through the help of President Booth, when the Mormons moved from Aintab. It was like a large “khan” . . . with large rooms divided into four parts, each family getting a part. The cooking and restrooms were outside. Most people used a gas burner inside their corner, but for baking and large cooking projects, they would go to the communal kitchen. Many of them used welfare funds from the Church until they found jobs and could make it on their own.” (Mary B. Ouzounian)

January 21–23, 1924. Elder McKay visits the “khan where are living in 13 rooms, 26 families, 200 persons. Rugs on cement and rock floors, charcoal burning in fire pots—only source of warmth—carpet looms, lace making frames. Beautiful rugs and magnificent hand-made lace gave evidence of skill and artistic ability.”

“Visiting rug factories—saw beautiful rugs. Also inspected beautiful needlework. Report given showing excellent work performed by members.” (J. W. Booth)

Emigration: While Armenian Saints continued to live, work, and worship in Syria, they also lived with faces turned toward “Zion.” LDS Armenians had emigrated out of Turkey/Syria since the 1890s. Many settled in Utah and became fully participating members of the Church community. The Saints in Aleppo and elsewhere continued to emigrate until, by the middle of the 1960s, most had relocated in the United States. So be to an LDS Armenian also meant that the exodus of the community, which had begun in the 1890s, had only recently come to an end.

October 8, 1902. Leaving Zara for “Zion.” Our two wagons were loaded and ready to begin our journey. . . . Many people holding on to the wagons, began following us, begging us to stay and not go to a country we knew nothing about. . . . We drove a short distance when suddenly we heard mother in the front wagon screaming, ‘Stop the horses, stop the horses.’ She had not seen Misag, her elder brother, but it was getting late, and the drivers drove the wagons faster to keep the crowd from catching up with us. There on the horizon near the bend of the road almost dusk, we saw three men doing an Armenian dance in the middle of the road with locked arms, their handkerchiefs waving above their heads. As we approached them, we recognized Misag as one of the men . . . More tears, more farewells, but finally we left them too behind us and we journeyed on into the dusk of the evening.” (Herond Nishan Sheranian, M.D., Odyssey of an Armenian Doctor, LDS Church History Library)

All during this time, persecution kept increasing—not only for us, but for all Christians—to such an extent that we finally decided to emigrate to Zion.” (Reuben Ouzounian)

Exhibit Section 7. Keeping the Faith:

While Armenian Saints have settled permanently and became citizens of the United States, most recall vividly their extraordinary history, and many continue traditions that were once so integral to Mormon group identity. Attention will be paid in this section to the rug- and lace-making skills of the Aposhians, Ouzounians, and Hindoians as a way of expressing, remembering, and keeping the faith with their Armenian heritage.

Note: In all the foregoing sections, use will be made of maps, documents, photographs, and artifacts drawn from the accompanying preliminary objects list [below] to tell this story. In addition, large graphics panels, photo collages, display cases, music, recorded voices, etc., will be part of the exhibit team’s resources. The use of these various design elements will be determined in the exhibit development process.

The “Objectives” and “Narrative” sections of the July 28, 1993, Phase II Review for the proposed exhibit on Mormon Armenians ended here. The following section of the review listed all of the historical artifacts, photographs, and documents that I had identified by July 1993 for display in the exhibit. They came from the personal collections of Mormon Armenians in Utah (Melva Emrazian, George Ouzounian, Mary Bezdjian, and George Z. Aposhian) and from the LDS Church Archives, Church History Library, and the Museum of Church History and Art.

Museums make things visible. In history museums, a professional staff strives to bring stories from the past out of obscurity. If effectively displayed, historical artifacts, photographs, and documents are the best media to help conjure the past into the present for the museum audience. It’s precisely here that the absence of the exhibit that was canceled in the summer of 1993 is most haunting. In 2023, I was able to locate some of those photos to help illustrate the written narrative. But the artifacts, the other photographs and historical documents? They are beyond my recall; they are beyond our view and remain in private hands, in museum storage, and filed away in the LDS Church archives.

If the exhibit had gone forward in 1993–94, museum patrons would have seen stunning Armenian needlework, hand-tied and woven rugs, and rug-making frames and tools. A cooking pot, spoon, and serving plate from an early twentieth-century Armenian kitchen, a prayer rug, missionary diaries, historic Church pamphlets, scriptures and a hymnal in the Armenian language, baptism and marriage certificates, personal histories, passports, letters of appointment to missionaries, and a plethora of historic photographs—all this and more. The result? They could have lit up our imagination, brought the past to life and welcomed us into the rich and complex religious, economic, domestic, and institutional lives of Armenian Saints and missionaries from 1884 to 1928 and beyond.

After everything these people went through—Armenians (and missionaries)—the thoughtful, faithful service, the failures, the uprooting of families because of conversion and emigration, the persecution, poverty, and peril, the terror of communal violence and genocide, the hard work and achievements—to have a museum exhibit honoring their lives canceled due to “politics” in 1993 was an ignoble betrayal. I felt it keenly then; I feel it now, more than thirty years later.

For three decades, I have carried this canceled museum exhibit with me—the phase reviews, the research notes, photocopies of journals, interviews, historic photos, maps, and books. And the memories. It has shadowed me from the US to Canada, from one profession to another, and from the religious community in which I grew up to another chosen later in life. The story of Armenian Mormons I had once hoped to tell as a museum curator, I have now tried to bring forward, though I can see that it is only a shade of what it could have been: a compelling, memorable exhibit seen by thousands of people crossing the threshold into the museum on West Temple Street in Salt Lake City. That said, the making of this hauntological exhibit helped me travel in time and mind; it renewed my profound appreciation and acquaintance with a handful of remarkable people.

Afterword

The Zadik Moses Aposhian Carpet

Zadik Moses Aposhian (born in Gaziantep, Turkey in 1870) became a master carpet weaver. In 1908, after having sent his wife and children on to Utah the year before, Zadik joined them. After settling in Salt Lake City, he entrusted a large carpet to Joseph Booth, the Mormon missionary who had returned from Turkey when the Armenian mission was closed due to the massacres of 1909. I learned about this in the summer of 1993 when interviewing George Zadik Aposhian (Zadik’s son, born in 1905) in his home in Salt Lake City while researching and preparing for the Church museum exhibit.

Figure 10: Zadik and Khatun Aposhian (Photograph provided by Church History Library and Archives)

According to the notes I kept at the time, George Aposhian said, “I was just a boy then. One day a man came to our door. I was standing next to father. I had never seen a grown man cry. He was asking my father to forgive him for what he had done. My father didn’t say a word. He just stood there looking at the man, and then closed the door.”

Then George Aposhian told me, as best I can recall thirty years later: “You see, it was Joseph Booth. My father had lent Booth his signature design carpet woven in Turkey—the work of a master weaver who shows to all the world his skill, his art, what he can do. Booth said he would show the carpet around to attract attention and help establish my father in business. Instead, Booth gave the carpet away to his brother-in-law, Elder James Talmage, as a gift. And here he was years later begging my father’s forgiveness. My father never forgave nor forgot, nor have I.”

[1] Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, translated by Peggy Kamuf (New York: Routledge, 1994), 63, 202.

[2] The city is now called Gaziantep.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue