Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 1

When Was the Last Time You Read a Romance Novel? | Ilima Todd, A Song for the Stars.

The desire to read emphasizes a basic generosity toward the Other that is the condition of all language. As Donald Davidson has argued, entering into language involves us in what he calls the “principle of charity,” an assumption that other people are intelligible and that they have something worthwhile to say. . . . The impulse to read, therefore, insists on the necessity of the Other—on our need for, fascination with, surprise by, dependence on others—even in moments of the most intense privacy and self-attention.

—Daniel Coleman[1]

When was the last time you read a romance novel?

My answer does not count. I recently read three for the sole purpose of finding one to review, but the previous time was certainly before college. In my English major we talked big talk about expanding the canon of literature, but even popular fiction courses left out romance novels. This canonical oversight is doubly so for the genre’s sexless subcategory that populates Utah bookshelves. Yet, these are the books I see at family gatherings when my cousin’s wife can steal a few moments away from her boisterous boys. These are the books my sisters will actually read, and that my high school best friend would slip me from her private collection so that we could live vicarious lives.

We saw in these books something worthwhile. The books provided what we wanted, whether it was sweet, sweet alone time, the joy of reading, or a love life (of sorts). Reading romance was our claim to something more, and to treat the genre as formulaic cheese-puff reading risks discounting what the female readers, female authors, and female protagonists have claimed for themselves.

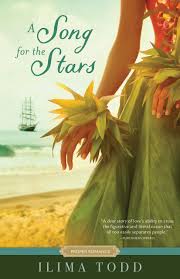

Take, for example, Ilima Todd’s A Song for the Stars. Given that it was issued as part of Shadow Mountain’s Proper Romance series, I assure you that this novel has the romance your reading heart has missed. The protagonist, Maile, is the daughter of a Hawaiian chief and against all odds falls for a foreign sailor landed on their shores. As far as I can tell, this novel is the first Proper Romance to not be about a white woman, which is also amazing for a romance sitting on a Deseret Book shelf.

In the book’s acknowledgements, Todd cites a 2012 writing workshop that inspired her to tell the story of her fourth-great-grandparents. This story did not fit Todd’s established genre of YA science fiction, though, and remained a side project worked on in stolen moments. It was not until her editors asked for a Hawaiian romance that Todd felt permission to write the book she dreamed of. Writing this book, to me, seems like Todd claiming space for her own ideas and the power to write her way into other genres, even if it took leaving the space in which she believed she belonged.

The story begins just before Captain James Cook and crew return to Hawaii in 1779, making the historical fiction just as much about “the contrast of two cultures colliding for the first time” (290) as it is about romance. Todd combines the story of the British captain’s subsequent death with the meeting of Todd’s ancestors, chiefess Papapaunauapu (referred to as “Maile” in the book) and British naval officer John Harbottle. The twist: John kills a man responsible for Captain Cook’s death in front of Maile, the fiancée of the now deceased man.

I am completely unsettled by the forgiveness and romance that blooms between Maile and John. While Maile slices John’s chest and abducts him, she shortly thereafter tends to the wound she’s caused and becomes John’s protector. She even teaches John the navigational skills that her fiancé taught her, which is either a full-circle moment or one that walks close to disrespecting the dead. In either case, Maile learns about circumstances justifying the otherwise unjustifiable actions that she and John have taken. Oh, and she learns to love again (this is a romance novel).

Circling back to Maile’s fiancé, Ikaika, it is worth noting that he is not a one-dimensional man-prop blocking the would-be lovers (RIP Kocoum from Disney’s Pocahontas), but a fleshed-out friend and companion to Maile. His death is a loss. I knew from the back cover that he would die, but it was still refreshing to feel the moment when it came. Ikaika’s loss remains palpable throughout the remainder of the novel, and Maile deals with the double-guilt of a survivor loving after love and learning to love the man responsible for her past love’s death.

Still, Maile claims power over her circumstances and more power in her partnering. While Maile and Ikaika’s relationship was positive, Ikaika was the teacher and Maile the student. In Maile and John’s relationship, Maile is fully in command. In order to claim this autonomy for herself, Maile first overcomes her distrust of the Other. She works through her negative feelings toward otherness to a place of questioning, learning, and mutuality. She exercises the “principle of charity” spoken of by Daniel Coleman and claims power through realization of her “need for, fascination with, surprise by, [and] dependence on others.”[2]

Unsettled is a good word for this story because while the surface is a romance, just beneath the waves you see the other European sailors’ disregard for the Hawaiian people and their culture—a harbinger of exploitation to come. This makes it hard at times to root for John even though he begins as a good man and then ends as a good man who better understands the culture and is in love with Maile. The real character growth is Maile’s, and with her in center focus it becomes easier to accept that John’s presence can be both good for her and good for her people and see that the long-term consequences of external forces on the islands do not need to be part of her story in order for it to be worth telling.

Maile’s story as it is easily sets up the outside critical discussion of colonialism, power dynamics, and the extent to which we are willing to forgive. The fact that the story involves romance formulas does not make it inferior but rather more accessible to a lay audience, which should democratize the conversation rather than close it off.

So, when was the last time you read a romance novel?

Romance is a room of women readers, authors, and protagonists that you do not need to visit in order for it to have worth, but the door is always open.

Ilima Todd. A Song for the Stars. Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2019. 304 pp. Paperback: $15.99. ISBN: 978-1-62972-528-4.

[1] Daniel Coleman, In Bed with the Word: Reading, Spirituality, and Cultural Politics (Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta Press, 2009), 14–15.

[2] Ibid.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue